Entering the Soane’s, you’re immediately engulfed by a visual tempest — a staggering accumulation of art, artifacts, and plaster casts squeezed into three adjoining London townhouses. There’s not a patch of bare wall or a breath of empty space. From floor to ceiling, every crevice groans under the weight of some ancient whisper: Roman fragments, Egyptian relics, architectural renderings, models, and sculptures in glass, bronze, and plaster.

Sir John Soane wasn’t just an eclectic collector — or, as a friend of mine once dubbed him more precisely, an eclector. He was a visionary architect who reshaped the very language of space and light. Born the son of a bricklayer in 1753, he quite literally built his way up the social and artistic ladder, brick by brick, mind by mind. His prodigious talent caught the eye of the Royal Academy, and his scholarship to study in Italy — the sacred rite of architectural passage known as the Grand Tour — exposed him to the ruins and radiance of classical antiquity.

There, amid the decaying grandeur of Rome, Soane absorbed not just proportion and geometry, but atmosphere — the way sunlight slips through arches, the melancholy of broken columns, the dialogue between shadow and stone. Returning to England, he translated that emotional architecture into the practical world of his commissions.

In his early years, Soane found patrons among the rising English elite who valued innovation cloaked in tradition. The Earl of Bathurst commissioned him to work on Lansdowne House, and later the Dulwich Picture Gallery would make him famous for pioneering natural light as an artistic medium in architecture. His designs balanced grandeur with intimacy — stately yet human, steeped in classical ideals but free of pomp. These early commissions opened doors into the higher echelons of society, where Soane’s name became synonymous with refinement and daring.

The Bank of England and the Birth of Modern British Architecture

By the late 18th century, his reputation had reached the crown jewel of commissions — Architect and Surveyor to the Bank of England. Here, Soane had the opportunity to redefine the architecture of power. Instead of fortress-like opulence, he envisioned a temple of trust and stability: a city within a city, full of softly lit rotundas, curving corridors, and domed halls.

Although later remodelings stripped away much of his original work and his signature domes were never fully adopted in the final iterations, Soane’s vision became the architectural DNA of British civic design. His emphasis on harmony, proportion, and illumination — on architecture as a moral and psychological experience — influenced generations of architects. Even today, echoes of Soane’s sensibility appear in British institutions that blend austerity with elegance.

But Soane’s true cathedral was his own home — the living collage that is now the Sir John Soane’s Museum. It was his laboratory, his reliquary, his dreamscape made solid. Mirrors double and distort, colored panes of glass tint daylight into a kind of secular stained glass, and narrow passages open unexpectedly into domed chambers that feel infinite. He turned space into theatre, and the house itself became his final — and most personal — act of architecture.

Each level of the museum, as our tour guide revealed, carried its own symbolic meaning. The basement, dimly lit and lined with figures of myth and mourning, represented the underworld — crypts, sarcophagi, and relics whispering of mortality. As you ascended, the atmosphere changed: light streamed through domes of glass, the architecture itself seeming to lift the spirit. The upper floors embodied the aspirations of humankind, rising from darkness into illumination. Even the kitchen, surprisingly one of the most significant rooms, celebrated this theme — its Pompeian-red walls glowing under a domed skylight that allowed sunlight and passing clouds to drift through, turning the space into a living meditation on the cycle of day and life itself.

I’m glad I took the one-hour guided tour; without it, I’d never have discovered the hidden paintings or learned the backstory behind Hogarth’s moral series — A Rake’s Progress — depicting the rise and ruin of one man’s debauchery and downfall. Secret doors swung open to reveal yet more paintings, each telling another cautionary tale, as though Soane had conspired with time itself to hide and reveal life’s tragedies.

The Love and the Loss

Before his fame and fortune, John Soane met Eliza Smith, a young woman of warmth and refinement who shared his artistic temperament. They married in 1784, and by all accounts theirs was a genuine love match — unusual in an era when social convenience often dictated union. Eliza became both muse and moral anchor to the restless architect, grounding his intensity with grace. Their home life, for all its grandeur, was intimate — filled with conversation, companionship, and mutual respect.

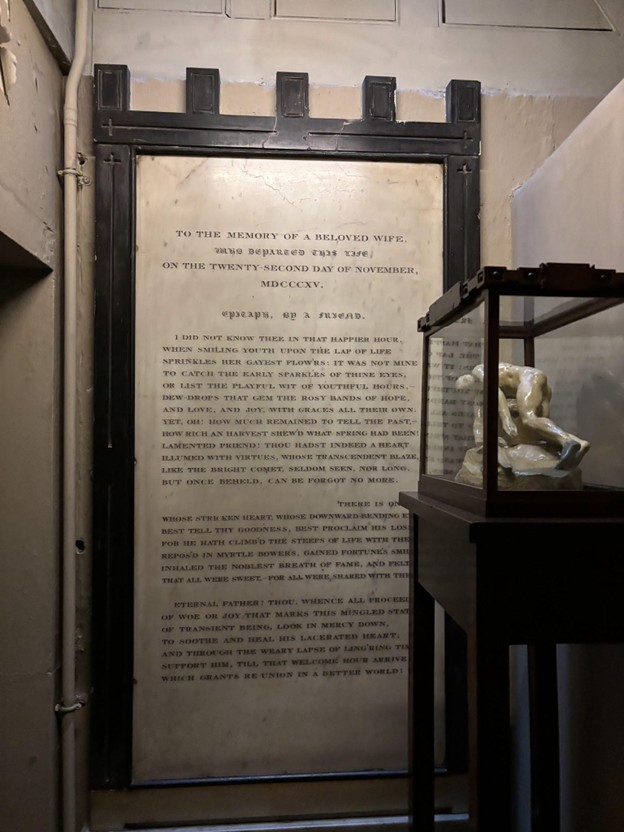

When Eliza died suddenly in 1815, Soane was inconsolable. The light that had filled his world dimmed. He transformed his grief into architecture, preserving her bedroom exactly as it was on the day she passed — untouched, a shrine to memory and devotion. Even in death, she remained present in his designs: the interplay of light and shadow, the melancholic beauty of his crypt spaces, the solemn poetry of his house-museum all speak of mourning sublimated into art.

Beyond the architectural marvels and curatorial density of the house, I found the most intimate relic of all — a love poem written by Soane to Eliza. Reading it brought tears to my eyes. His words pulsed with devotion — raw, unguarded, timeless. If only in real life one could meet such an affectionate, loyal, and steadfast partner. Eliza, I thought, was a very lucky woman.

To step inside Soane’s world is to step into the mind — and the heart — of a man who refused boundaries. From humble beginnings with mortar and trowel to a labyrinth of eternal curiosities, Sir John Soane remains the ultimate eclector: an artist who built not only in stone, but in feeling — shaping the British imagination one luminous curve at a time.

Sir John Soane’s Museum

Address:

13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields

London WC2A 3BP

United Kingdom

Website:

🔗 https://www.soane.org

🕓 Opening Hours

- Wednesday to Sunday: 10:00 AM – 5:00 PM

- Closed: Mondays and Tuesdays, and major public holidays

(Last entry is usually around 4:30 PM.)

🎟️ Admission

- Free entry to the museum (as per Sir John Soane’s original wish that his home remain open to the public).

- Guided tours and special exhibitions are ticketed — you can book them online through the official site.

🗝️ Guided Tours & Highlights

- Highlights Tour (1 hour) – Highly recommended! It includes access to secret panels, the hidden Hogarth paintings (A Rake’s Progress), and insights into Soane’s personal life and architectural symbolism.

- Private tours and after-hours candlelit tours are occasionally available — these sell out quickly.

- Advance booking is essential for all tours; walk-ins are for general entry only.

👉 Book directly here: https://www.soane.org/whats-on

Getting There

- Nearest Underground:

- Holborn Station (Central & Piccadilly lines) – 3-minute walk

- Chancery Lane (Central line) – 5-minute walk

- Holborn Station (Central & Piccadilly lines) – 3-minute walk

Nearby attractions: Lincoln’s Inn, The Royal Courts of Justice, and the British Museum (about a 10-minute walk).