Picking up Homer’s Odyssey and reading it ‘cold’ is not a good idea. Reading it is essential, as it (together with The Iliad) is the foundational text of Western civilization, but a primer is also essential. Think of it as gently tasting a fine wine before you drain the bottle…

The book at hand was written in German by Prof. Jonas Grethlein. He is chair in Greek literature at the University of Heidelberg. Originally published in 2017, it has just been translated by Sabrina Stolfa.

Grethlein manages to plumb depths of the Odyssey that even those who have read it two or three times will find illuminating, and maybe even astonishing. As he states in Chapter 1, “the Odyssey has influenced Western literary history more than any other work.”

There is an important word in German that the translator has opted to retain: Bildungsroman, meaning a novel dealing with the formative years of a subject. “The Odyssey,” writes our author, “adopts a different type of narration than is employed in the coming-of-age narrative, and I would argue that the type of narration is linked to the ancient view of personality.” This central theme, set out in Chapter 2, must be kept in mind as one reads both this book and Odyssey.

It is expressed most vividly in the meaning of suspense, which in the case of most ancient literature, including Odyssey, relies on plot rather than characters. Free indirect speech is lacking. So, what to a modern reader appears to be “a deficient image of the human being” is not a defect, but a consequence of how the ancient Greeks wrote. “Odysseus is the hero of the epic, but it is not the processes of his consciousness that captivate the audience, so much as his adventures.”

It is more like a ‘Boy’s Own Adventure’ than a Jane Austen novel. “While Jane Austen offers an immersion in individual emotional worlds, the Homeric narrator primarily presents the audience with the question of how the plot will arrive at the anticipated ending…The stories told within the story of the Odyssey,” writes Grethlein, “reveal the complex relationship between narrative and experience.”

Thus, a first-time reader of Odyssey will likely have some feeling of disorientation, but it is in this disquietude that Grethlein positions his text. “This strangeness offers an opportunity to question modern ideas of narrative and personality.”

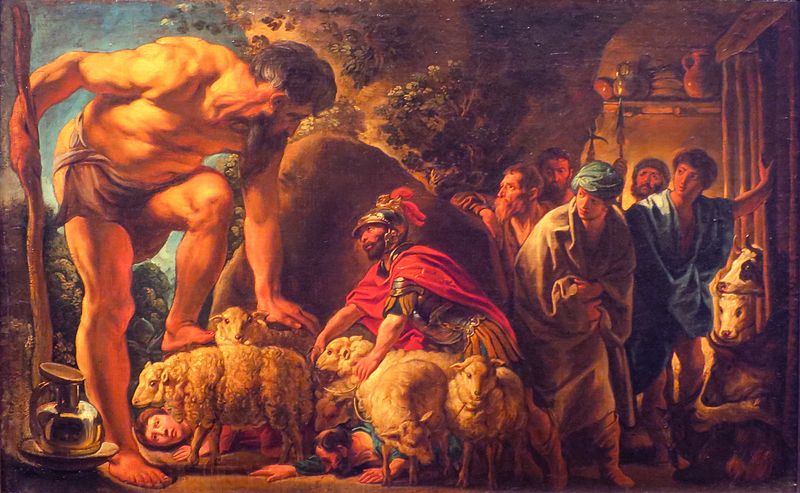

The hinge of the book comes in Chapter 6, where the author presents textual evidence of such a stark and disturbing nature that it becomes difficult to maintain the hero aura of Odysseus. The definition of that word is multivalent: a hero to one person might be regarded in a less favourable light by another. Odysseus might best be term a ‘flawed hero.’ Grethlein’s argument is based on a comparison between the scene where Odysseus kills the suitors of his wife, with the scene where the cyclops Polyphemus kills the friends and soldiers of Odysseus.

In the case of Odysseus, he invades the dwelling place of Polyphemus and consumes his food in his absence. “This parallel does not reflect well on Odysseus: why should he accuse the cyclops of violating the laws of hospitality when he has himself intruded into his cave? To put it bluntly, Odysseus kills the suitors for a transgression he is himself guilty of.”

Furthermore, the “likening of the killing (of the suitors) to the arbitrary hunt of an animal does not cast a favourable light on Odysseus’ revenge on the suitors.”

The slaughter of the suitors, “rather than illustrating the hero’s bravery, emphasizes his animalistic aspect. He is depicted as being merely akin to the lion, but the image emphasizes the bestial dimension of murder.”

A knowledge of the actual words in ancient Greek are the way to understand the parallel Homer actually makes here, and it is Grethlein’s key insight. “Antinous is the first suitor whom Odysseus kills.” Quoting from the text: “and through his nostrils there burst a thick jet of mortal [andromeos] blood.”

Our author notes “the adjective andromeos is very rare; it is used in just three other places in the Odyssey, and all occur in the cyclops episode. The repetition of this word evokes the man-eating cyclops, inviting the audience to compare Odysseus to Polyphemus and the murder of the suitors to the cyclop’s dietary transgression.”

The blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseus and his men is the other key moment I will discuss here. The scene was widely depicted on pottery going all the way back to 700 BCE, with the act itself showing soldiers holding the spear to the head of Polyphemus, while above that are eyes staring out at the viewer. While the cyclops had only one eye, Grethlein explains that two are shown “due to the pictorial scheme for frontal depictions.”

More importantly, “the depiction of Polyphemus’s blinding is an invitation to reflect on the act of seeing images…We become engrossed in the narrated action or painted scene without forgetting that it is a representation.” This is but a subset of a much larger “artistic preoccupation with the gaze,” as it is known to historians of ancient art, “especially in the Imperial period” as witnessed by wall paintings in Pompeii. Homer’s interest “in the gaze” is the subject of chapter 5.

“In the Odyssey,” explains our author, “the gaze is multifaceted – it is a means of recognition; it conveys admiration, and it also serves to express control and aggression.” The latter is most notable “in the confrontation between Odysseus and the suitors.”

A book of rich insights that will be welcome even by experts in the study of Homer, I recommend reading this especially for those who have not yet read the Odyssey. More than just a primer, it will provide the novice reader (perhaps senior high school or college students) with the intellectual grounding needed to comprehend this foundational text.

Image credit: Odysseus in the Cave of Polyphemus – Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) – Pushkin Museum. The book by Grethlein has several B&W illustrations.Reading the Odyssey: A Guide to Homer’s Narrative is by Princeton Univ. Press. It lists for $30.

In July 2026, a major film will be released!

The Oscar-winning director Sir Christopher Nolan’s vast film adaptation of the Greek epic The Odyssey, was filmed on location across five countries, on land and at sea aboard a replica Greek ship. Starring Matt Damon as the hero, the film is the largest adaptation of Homer’s poem since the 1954 film Ulysses.