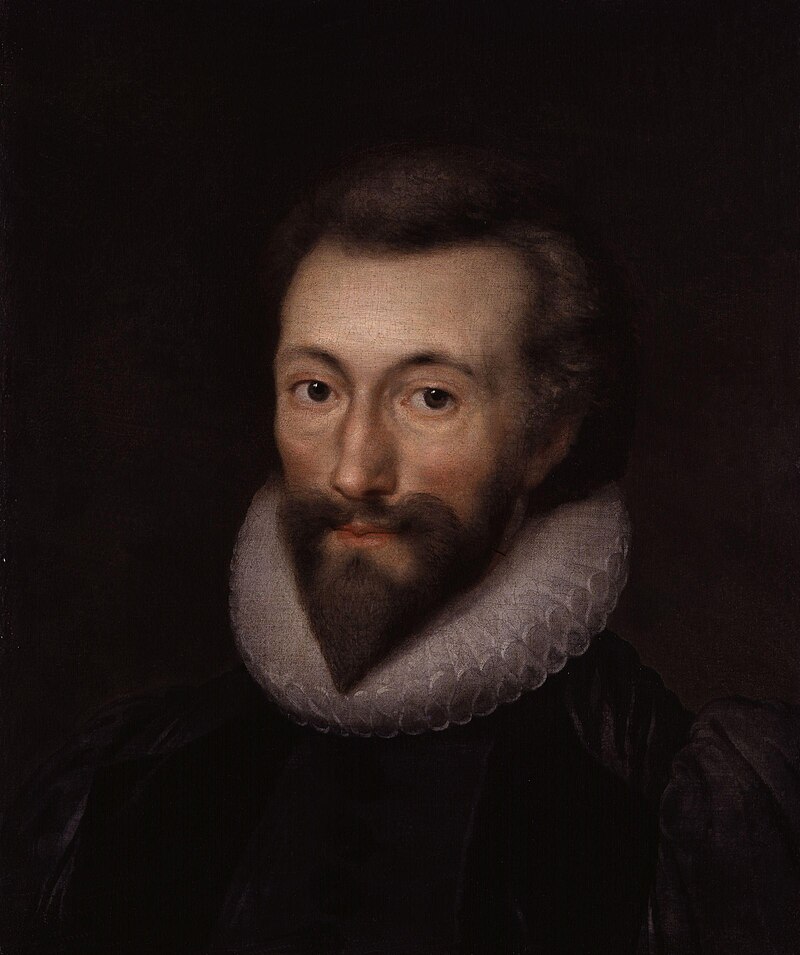

Image: John Donne (1572-1631)

This book on imagination in English literature of the 1500s and early 1600s is edited by professors at two institutions in Canada (their bio data is below); it grew out of a 2019 meeting of the Renaissance Society of America held in Toronto. In addition to the editors, 12 experts have combined their talents to write this important contribution to our knowledge of early modern English literature.

Before discussing what is in the book, I’d like to set the stage (as it were) by mentioning an important point that it elides.

As explained by Kibbee (2018: 196), Guglielmo Gratarolo’s 1553 book (translated into English as The Castle of Memorie in 1562) includes Aristotle’s definition of memory as “an imagination, that remaineth of such things as the sense had conceived.” [see note 1] As this was available in English by 1562, it is entirely likely that various writers were aware of it, even if they had been unable to read the quote by Aristotle from classical sources. Surprisingly, neither Gratarolo nor Aristotle’s definition of memory as an imagination can be found in the book under review, and Kibbee’s thesis is not referenced in any chapter.

Thus, we find in a chapter on the “Imagination of Eating,” the following line: “Thanks to the imagination and memory, it is possible to desire food that is not immediately present.” Here, memory and imagination are regarded as entirely separate, but we know from Aristotle, via Grataloro, that memory is an imagination.

My headline derives from the work of John Donne (lead photo), who “understood the imagination as the brain’s meeting place for opposites: of reader and author, body and soul, humanity and divinity. The imagination emerges as a necessary yet imperfect faculty.” This comes in a chapter by Anton Bergstrom, who teaches at the University of Waterloo (where I earned two bachelor degrees). He did his 2020 PhD on Donne.

“The imagination, for Donne,” writes Bergstrom, “takes part in not only forming mental images of external sensible forms, but it also seems to facilitate the conception of abstract mental concepts, such as time.” Indeed, Donne himself created the very best description of time. In his 1624 book Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, he describes time as an “Imaginary halfe-nothing.” Bergstrom says that by these words, Donne is “suggesting that time is something humans can assign a mental concept to even if it is not something we can ever directly perceive through the senses.” This is a key element that comprises “The Embodied Imagination,” which is the title of this book.

Pavneet Aulakh (Vanberbilt Univ.) also engages directly with Donne, who warned that imagination can distort reality. “Donne goes even further than Shakespeare’s Theseus (in A Midsummer Night’s Dream) in figuring the imagination as a visual echo-chamber where misperceptions multiply in a chain reaction.” Anyone who has watched Bridgerton gets a masterclass in this, when Queen Charlotte misidentifies Lady Whistledown. It sets off a chain reaction amongst the ‘ton’ who collectively comprise a vast echo-chamber.

In an elegy composed on the death of Donne, Thomas Carew drew a startling analogy. “Easily lost within Carew’s metaphorical fireworks,” writes Aulakh, “is that in his preaching Donne’s ‘brave soul’ functioned like a telescope of such power that its concentrated light could liquify viewers’ hearts.” Aulakh elaborates the astronomical metaphor:

“Just as Galileo framed the telescope as a superior, surrogate eye, a medium and maker of images free of the distortion produced by its human counterpart, he is simultaneously both an eye-piece, or lens, through which audiences see, and substitute inner eye generating representations to stock their memory and to stimulate their understanding.”

This key insight regarding the eye is best read in conjunction with a chapter by Darryl Chalk (Univ. of Southern Queensland, where I am a Research Fellow). There, Chalk quotes the French writer Pierre de La Primaudaye, “whose The French Academie, first translated and published in England in 1584, was popular enough to be reprinted multiple times over the next several decades. He defines the imagination as ‘amongst the internal senses as it were the mouth of the vessel of memory’ because it is ‘the eye in the body, by beholding to receive images that are offered unto it by the outward senses.’”

The reader is already put on notice by the editors, in their Introduction, to be attuned to such things: “Imagination is the vehicle that operates between the intellect and sensory experience,” they write. For example, the chapter by Deanna Smid (Brandon Univ.) “explores the distinction between the musical fantasy our senses hear in Shakespeare’s Pericles and the music of the spheres that our souls, guided by Pericles, access through our imagination.”

Smid explores the 1604 book by Thomas Wright, the Passions of the Mind. “Wright turns to divine providence to explain that music influences the body just as the imagination translates the material into the spiritual.” Smid turns to another book on the passions, the 1640 A Treatise of the Passions by Edward Reynolds. He “posits that the imagination can persuade by ‘secretly instilling’ its ‘eloquence’ into the listener.” Smid uses this in her further examination of the play Pericles, in which “Marina’s musical accomplishments reveal her immense powers of persuasion, particularly through her imagination.” This power of music is another key element that comprises “The Embodied Imagination.”

But the play Pericles in this same scene brings to the fore yet a third key element. After Marina’s song, Pericles encourages Marina to continue the story of her parentage by assuring her “I will believe thee/And make my senses credit thy relation/To points that seem impossible.” In these words, writes Smid, Pericles “demonstrates that he works to control his senses and understanding, a control only possible by means of the imagination.”

This leads Smid to quote from Francis Bacon, who understood this completely. “Sense sendeth over to imagination before reason have judged: and reason sendeth over to imagination before the decree can be acted.” Here we see a third key element in “The Embodied Imagination”: reason.

There is much else to consider in this fascinating and most valuable book, but I will leave the reader here with a fourth key element that is handed to us in the Introduction, one that must be borne in mind when reading these early modern texts: “The premodern imagination belonged to the body, but after that it belonged to the mind.” This great gulf that separates us from the era of Shakespeare is why truly understanding his plays – and the works of many others – is so difficult. This book shows why, with a little imagination, it is worth the effort to learn how the bridge that gulf.

About the Editors

Mark Kaethler is Academic Chair of Arts at Medicine Hat College in Medicine Hat, Canada, and the author of Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media: Old Words, New Tools.

Grant Williams is an Associate Professor in the Department of English at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. He co-edited the essay collections The Shakespearean Death Arts (Palgrave, 2022), and Memory and Mortality in Renaissance England (Cambridge, 2022).

Note 1: Aristotle’s theory of imagination is rooted in his analysis of sensation in De Anima (On the Soul).

There is a typo on page 184: “is much gold” should be “is so much gold”

Reference:

Kibbee, M. (2018). The Mind Transfigur’d: Brain, Body and Self in the Drama of Shakespeare and Marlowe. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Cornell University.

Image: painting of John Donne, held by the National Portrait Gallery, London. PD-Art. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Historicizing the Embodied Imagination in Early Modern English Literature is by Palgrave MacMillan (Springer). It lists for $139.99