The intersection between architecture and science in the 1500s is one that remains largely unexplored. By looking at the art of Wendel Dietterlin (1550–1599) a whole new approach to the topic has now been published.

The author of this innovative study is Elizabeth Petcu, a senior lecturer in Architectural History at the Univ. of Edinburgh. In an essay she wrote for Cambridge University, Petcu explained her rationale for this book:

“In composing The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science, I combined methods from art history, architectural history, the histories of science and knowledge, and postcolonial critique. I departed from more typical histories of architecture by foregrounding other artistic media, such as drawing, painting, print, and sculpture. Because the book emphasizes empirical knowledge and visual practices of research across art, architecture, and science, it was also important to me to assess not only images, but also the processes whereby such objects were formed, disseminated, and critiqued.”

While built architecture does feature in the book, Petcu concentrates her attention on etchings Dietterlin created for his book Architectura that visualized and physically embodied syntheses of the media she wrote of in ways that “no prior architectural treatise had.” His book “materialized over three installments in 1593, 1594, and a final, summative installment in 1598. Each appeared first in German and then in bilingual, Latin-French adaptations.” The lack of an English edition certainly goes some way to explaining why a scholarly study of Dietterlin’s great work has been largely neglected until now. “Although the scientific qualities of architectural ornament have largely gone unheeded by historians,” writes Petcu, “the subject in fact offered Dietterlin exceptional opportunities for exploring natural philosophical themes.” The themes she studies here include “the nature of space, the behaviour of light, the qualities of materials, the tectonics of complex structures, and the mechanics of moving bodies.”

The foundational text for all architects of the early modern period was the Roman Vitruvius: his was the only architecture book to survive to the Renaissance. “Despite its debts to prior Vitruvian literature, Dietterlin’s First Book title page presented the radical idea that images can embody the interdisciplinary intelligence of architecture.” Petcu asserts that the title page “asserted that architectural images can rival building as the ultimate goals of architectural invention.” Because these drawings were never actualized as real buildings, how Dietterlin and other makers of such images “adopted and shaped artistic and scientific practices of visual research remain obscure.” Shining a light on this “nexus of art and science” is what Petcu sets out to do here.

In the case of a real building, Petcu brings to our attention the Hall of the Strassburg Masons and Stonecutters. “The printed origins of the Hall’s painted botanical grotesques indicate that, by the 1580s, the masons saw print culture as an artistic resource…This was a signal moment in the history of architectural images and empirical philosophy.”

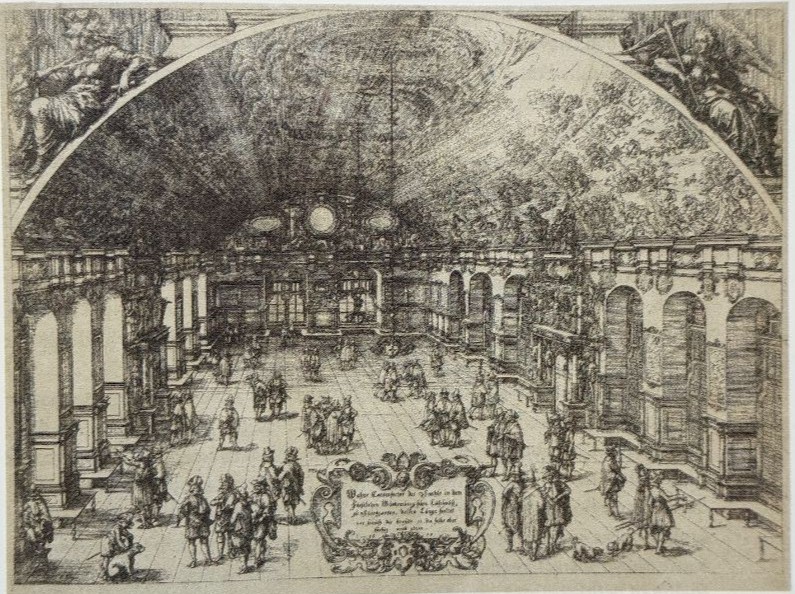

In Stuttgart, Dietterlin was fortunate in having as a good friend Heinrich Schickhardt, owner of the richest architect libraries of the Renaissance. Dietterlin certainly developed many ideas as he pored over the 525 books in the library. Given the opportunity to put his art into practice, he worked for Duke Ludwig, and became artistic director of the Great Hall in Stuttgart (lead photo).

“Few spaces in northern Europe had ever synthesized painting, sculpture, and architecture to such profound effect. By combining the Great Hall’s celestial and terrestrial scenes as well as its disparate media into an immersive, material, temporal, and spiritual totality, Dietterlin and his team forged an artificial microcosm.” Alas, it was destroyed in the 19th century.

A few years after his work in Stuttgart, Dietterlin drew the title page for his Architectura book. It took the form of a shield, whose meaning at first sight seems merely pleasing. But in that era, “shields often depicted worlds or described the cosmic order. In revolving around the shield, Dietterlin’s design poses the treatise as a mirror of the universe and the cosmic order and, in nod to empirical philosophy, frames the description of the observed universe as the goal of the architectural image.”

As for Architectura itself, Dietterlin’s ambition was “as a gargantuan pictorial undertaking.” It consists of a “mammoth corpus of 164 drawings and sketches.” Most of these originals are preserved today at a museum in Dresden. Petcu’s text runs to 414 pages, with about half of them containing an illustration (many in colour). The result is a resplendent book that should be studied by anyone interested in early modern science and architecture.

There is one typo: ats should be arts, on page 30.

Petcu’s full essay can be read at:

Image: Friedrich Brentel, “Great Hall of a pleasure palace with microcosmic ceiling painting devised and realized by Dietterlin (True Counterfeit Image of the Room in the Princely Pleasure Palace in Stuttgart),” 1619. Engraving, 15 1/2 × 20 1/2 in. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung, A 31982, Stuttgart. © Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science: Wendel Dietterlin and the Rise of Empirical Investigation is by Cambridge University Press. It lists for $120.