Special Editorial Note: This article will appear in the 10th anniversary edition of The Covent Gardener, a superlative magazine published in London. It was written by David Rooney, and is republished here by kind permission of the CG editor. More details at the conclusion of this article.

Image: David Rooney

No wonder it became so unpopular. There it stood, this new-fangled timekeeper that was looking so imperiously down on everybody. Some politician had decided to keep the population in line, and on time. And he’d done so by planting this in their midst. It cast a shadow – metaphorically as well as literally – over the lives of the people.

When the curious locals had got used to the newly erected sundial column that had been installed at the heart of their great city, it’s fair to say that they hated it.

A local playwright at the time made one of his characters exclaim, ‘the gods damn that man who first discovered the hours, and first set up a sundial here, to cut and hack my day so wretchedly into small pieces! When I was a boy, my stomach was the only sundial, by far the best and truest. It used to warn me to eat. But now, what there is, isn’t eaten unless the sun says so.’

Some people even called for the column to be torn down with crowbars, such was the fury of the local population. After all, they were hungry! And now they had to obey the clock, not their own stomachs, when they wanted to break for lunch.

Now, it probably wouldn’t be a surprise if that’s how the seventeenth-century residents of Covent Garden reacted to the arrival of the sundial column that came to define Seven Dials. Its 1980s successor still looms over passers-by heading for lunch today.

But I’m not talking about the Covent Garden column, built in the 1690s to the requirements of Thomas Neale, MP. Instead, we need to go way further back. Nearly 2,000 years, in fact. Because the sundial I’m referring to, the one that caused so much strife to local playwrights, was built in the year 263 BCE – in Rome.

Picture the scene: the Roman politician Manius Valerius Maximus was standing proudly on the elevated rostrum at the heart of the Forum. In front of him were huge crowds, eager to celebrate their elected consul who had commanded Rome’s military forces to victory on the island of Sicily.

And there beside him, on a tall column that bore his name, was the sundial he had looted from the Sicilian city of Catania. It was to be Rome’s first ever public timekeeper.

The thing is, it got off to a pretty good start. Everybody knew that triumphal columns in public spaces like the Forum were symbols of military power – Rome’s power. In that sense, this one was no different. It showed that Rome was on top. But the thing that made Valerius’s column different – the sundial – came to have an insidious effect on everyday Roman life.

Before long, the Forum sundial was joined by dozens more across Rome. And they had the same effect as clocks do today. They were designed to regulate and control the myriad daily activities of Rome’s citizens. To keep them in line.

There’s another parallel with Covent Garden. Like the Seven Dials column, the Roman Forum sundial was pulled down nearly a century after it had been erected. But, unlike Londoners, who had to wait two centuries for a replacement, the Romans got a new sundial immediately. To their horror, it was even more accurate than the first.

It got yet worse a few years later. The hated sundials of Rome were joined by a new public timekeeper at the Forum. This one was a water clock – so it ruled the sleeping hours of Romans as well as their waking ones.

Wherever we look in history, we see tall timekeeping towers or columns, set up by rulers to keep the population in order.

Take the Tower of the Winds, for example. Built in Athens in about 140 BCE, it is one of the best-preserved buildings from the ancient world. It stands fourteen metres tall and takes the form of an octagon, with each of its walls carrying a sundial. Perhaps the area should have been known as Nine Dials?

Or look at the city of Verona under the Gothic king Theodoric. In the year 507, he commissioned a huge acoustic water-clock tower for the city. Like Rome’s water clock, it displayed the time for all to see. But this one sounded it, too – strangely and violently, apparently. Imagine hearing the hours screeching across Verona’s streets, day and night. Theodoric said its purpose was to let people ‘decide how best to occupy every moment’. I bet he’d have loved today’s time-management apps.

But it wasn’t just the Greek and Roman empires that went in for temporal tower technologies. Across imperial China and Japan, towns and cities had drum and bell towers fitted with water clocks, often centred on marketplaces. When the drums sounded, you got up and went to work. When the bells rang, you could get some rest. It wasn’t optional. You had to obey.

And if you explore any city in a country that used to be part of the British Empire, chances are you’ll find a tall clocktower looming over the streets. A clocktower built by the British, to British designs, with a British-made clock mechanism inside. What tune would the bells sound? The Westminster chimes, of course.

Time moves on. Today, clocks are everywhere. They’re in our pockets, of course, and on our wrists, and tucked away in the corners of all the screens we spend so much time gazing at.

But time isn’t just for looking at (or listening to) anymore. Clocks hidden away in data centres, mobile phone networks, satnav systems and power stations keep the modern world working. Without clocks, our lives would grind to a halt.

But that doesn’t mean we have to like it. Next time you feel that time’s not on your side, think back to those poor Romans more than two millennia ago. Their lives were ruled by the clock, too. And they made sure everybody knew what they thought of it!

David Rooney is a historian of technology and former curator of timekeeping at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

His latest book, About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks (Norton: 2021), explores the hold these extraordinary devices have over us.

For more on David Rooney:

https://rooneyvision.substack.com/p/introducing-rooney-vision

Now, to the magazine in which this article will appear: https://thecoventgardener.com/

The Covent Gardener magazine is dedicated to exploring and celebrating the colourful area that is Covent Garden. Focusing on community, art and history. We cover quirky and unusual stories, providing a unique insight into one of the most incredible places on the planet.

Sun News Austin highly recommends this delightful magazine, so subscribe or give a gift subscription before the 10th anniversary issue gets published!

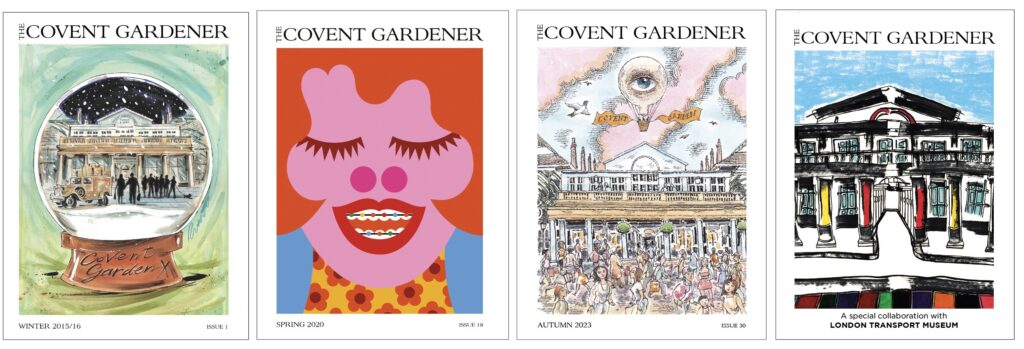

The Covent Gardener magazine turns 10 this September. It is is a fiercely independent, highly illustrated print magazine celebrating Covent Garden — one of London’s most historic and vibrant neighbourhoods in London.

To mark our birthday, we’re publishing a special bumper issue featuring 10 favourite stories from the past decade, from Covent Garden’s famous donkeys to the Watercress Queen, Eliza James. As part of the celebrations, we’re thrilled to share one of these stories exclusively with the Sun News Austin; a piece Before Our Time, whether in ancient Rome or 17th-century London, public clocks have always been more than decorative.

The anniversary issue is available to pre-order now, or can be picked up from Covent Garden’s London Transport Museum, Benjamin Pollock’s Toyshop, the Royal Opera House, and the Royal Academy.

www.pieropublishing.com Instagram @thecoventgardener