The Arts and Crafts movement that began in England in the 1840s and 50s still elicits awe. Its range of infiltration into everyday life is the motivating force behind an exhibit at the Harry Ransom Centre in Austin. What curator Christopher Long called a “reactionary movement” in its early years became the bedrock of the American cultural experience in the early 20th century.

Leading a large group through the exhibit on March 6, Long explained that “as a curator, I get to do something really fun: I get to play in other people’s attics. In this case one of the world’s most exotic attics is right here at the Ransom Centre.”

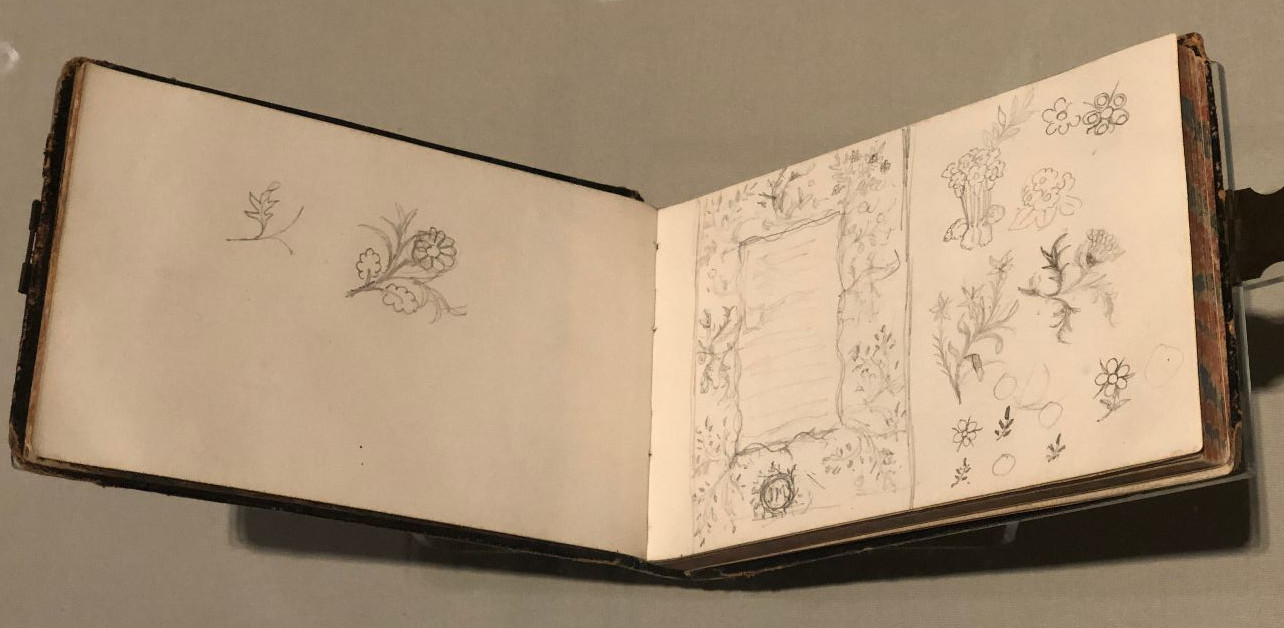

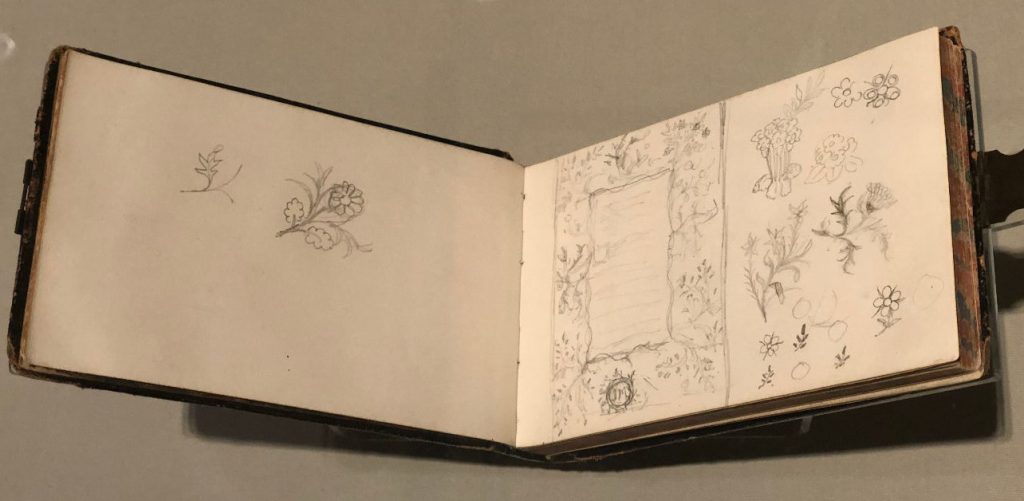

In coordination with fellow curator Monica Penick, also a University of Texas professor, they pondered “what’s the craziest thing that we want for this exhibit they probably don’t have?” One thing they wished for was a sketch book of John Ruskin, one of the founders of Arts & Crafts. “Sure enough they did have it!” said Long. They also found a sketch book of William Morris, who became the greatest exponent of A&C in the latter half of the 19th century. The sketches show his method of developing patterns for wallpaper that adorned countless homes. Both treasures are on display.

Long pointed out a vase by Christopher Dresser, “the first industrial designer,” whose existence highlights “a massive split” in the A&C movement, namely “should we make products for everyday life by hand or machine?” For Dresser, who was born in 1834, the answer was machine, for Ruskin, born in 1819, the answer was by hand. “That split runs through the entire A&C movement,” Long explained.

The catalogue for this exhibit, The Rise of Everyday Design, is published by Yale, and is available at the Ransom Centre for $60. This large and heavy book is beautifully produced and well worth the price, but there are things in the Ransom Centre exhibit not included in the catalogue. A special little gem is a photograph of the Crystal Palace under construction in London in 1851. As one of only two construction photos in existence, it assumes great importance; in the exhibit it is set into a wall whose entire surface is covered with an image of the Crystal Palace.

This will be familiar to those who watched the latest episode of Victoria on PBS, broadcast just a few days ago. The brainchild of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, it was one of the greatest crown jewels of her long reign, and began the idea of holding world expositions. Some of the people who began the A&C movement viewed the crafts on display at the Palace. “A lot of what was being displayed there was bad in terms of aesthetics,” said Long. It spurred them to create something better, and while no one at the time called it Arts and Crafts, that is the term we now attach to the entire range of things from lamps and plant stands to entire homes that developed over the decades.

This will be familiar to those who watched the latest episode of Victoria on PBS, broadcast just a few days ago. The brainchild of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, it was one of the greatest crown jewels of her long reign, and began the idea of holding world expositions. Some of the people who began the A&C movement viewed the crafts on display at the Palace. “A lot of what was being displayed there was bad in terms of aesthetics,” said Long. It spurred them to create something better, and while no one at the time called it Arts and Crafts, that is the term we now attach to the entire range of things from lamps and plant stands to entire homes that developed over the decades.

Here are just two of many things to look for as you tour the exhibit, one high and one low. At the high end is the world’s most perfect book, The Works of Chaucer, published by a press established by Morris in 1896. It is second in importance only to the Gutenberg bible on permanent display at the Ransom Centre. At the low end, look for a glass display case featuring a catalogue by the furniture company Come-Packt, founded in Ann Arbor in 1907. They were the original IKEA, selling furniture parts that the buyer had to assemble. That catalogue and all the other ephemera in the case was purchased for this exhibit on eBay! It’s the sort of material a fine museum never collects, but in this exhibit we see just how important it is to put the everyday value of the Arts and Crafts movement in context.

See this landmark exhibit at the Harry Ransom Centre before it ends July 14.

Photo captions: William Morris notebook, which was displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1934 for the centenary exhibition in celebration of Morris’ birth. In the collection of the Ransom Centre.

Photo 2: A plant stand (1904-1918) made by Charles Limbert Furniture Co. of Grand Rapids, Michigan and (after 1906) Holland, Michigan. In a private collection. And at right a Limbert chair from 1910. In a private collection.