Thanks to a loan of more than 100 works from the Tate Gallery (London), Texans can now revel in some of the greatest works of Surrealism. They are on view now at the Dallas Museum of Art.

“Surrealism wasn’t just a movement or a singular artistic style, it was a way of life,” said Sue Canterbury, Curator of American Art at the DMA. “This exhibition offers our viewers a glimpse into this revolution of the mind and the evocative, fantastical and often unsettling.”

Surrealism taps into the subconscious: not to be confused with the unconscious, which was discovered by Carl Carus, as published in his 1846 book Psyche. Many attribute both to the work of Freud, but it was his influence as the explorer of the subconscious that animated those who created surrealist works of art. They believed the creativity that came from deep within a person’s subconscious could be more powerful and authentic than any product of conscious thought. This includes the interpretation of dreams, so when viewing this exhibit let your mind wander into the realm of dreams you may remember. One thing that most dreams have in common is that they abandon reason; do not approach these paintings as you would a collection of Rembrandts or Renoirs! Instead of logical sense, the surrealists relied on the ‘superior reality’ of the subconscious.

The early 20th century was shaped and expressed to a large extent in manifestos. For example, Russian Futurism applied new aesthetic principles to poetry and writing, but it was dominated by principles originating from Futurist painting. In 1928, Sergei Tretyakov wrote “The Futurist painting was not a painting, but an insult in colors, an insult intended for the whole of fine arts.” This parallels the manifesto that defined Surrealism.

As described by the Museum of Modern Art (NY), “In his 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, Andre Breton argued for an uninhibited mode of expression derived from the mind’s involuntary mechanisms—particularly dreams—and called on artists to explore the uncharted depths of the imagination with radical new methods and visual forms. These ranged from automatic drawings to hyper-realistic painted scenes to uncanny combinations of materials and objects.” Like Futurism, Surrealism spit in the eye of the art establishment: an insult whose goal was the overthrow of that very establishment.

A century on, the Surrealist works now hang in the most prestigious art museums, but we can now see it as but a passing phase, one in a long line of “isms” the art community has created. The only question for the visitor to such museums today is whether or not they like it.

The visual artists who first worked with Surrealist techniques and imagery were the German Max Ernst (1891–1976), the Frenchman André Masson (1896–1987), and the Spaniard Joan Miró (1893–1983). All three are on display here at the DMA.

Masson’s free-association drawings of 1924 are curving, continuous lines out of which emerge strange and symbolic figures that are products of an uninhibited mind. Breton considered Masson’s drawings akin to his automatism in poetry. We see here his work entitled Sirens. The accompanying description states that “For the practice of automatism, Mason prescribed an ‘abandonment to inner tumult.’ The result was that ‘under my fingers involuntary figures were born…often disturbing, disquieting, unqualifiable.’” This certainly describes Sirens (1947), and like many of his drawings, it draws on classical mythology. I mentioned ‘reason’ earlier. This is what Masson stated: “For those of us who were young Surrealists in 1924, reason was the great ‘prostitute.’”

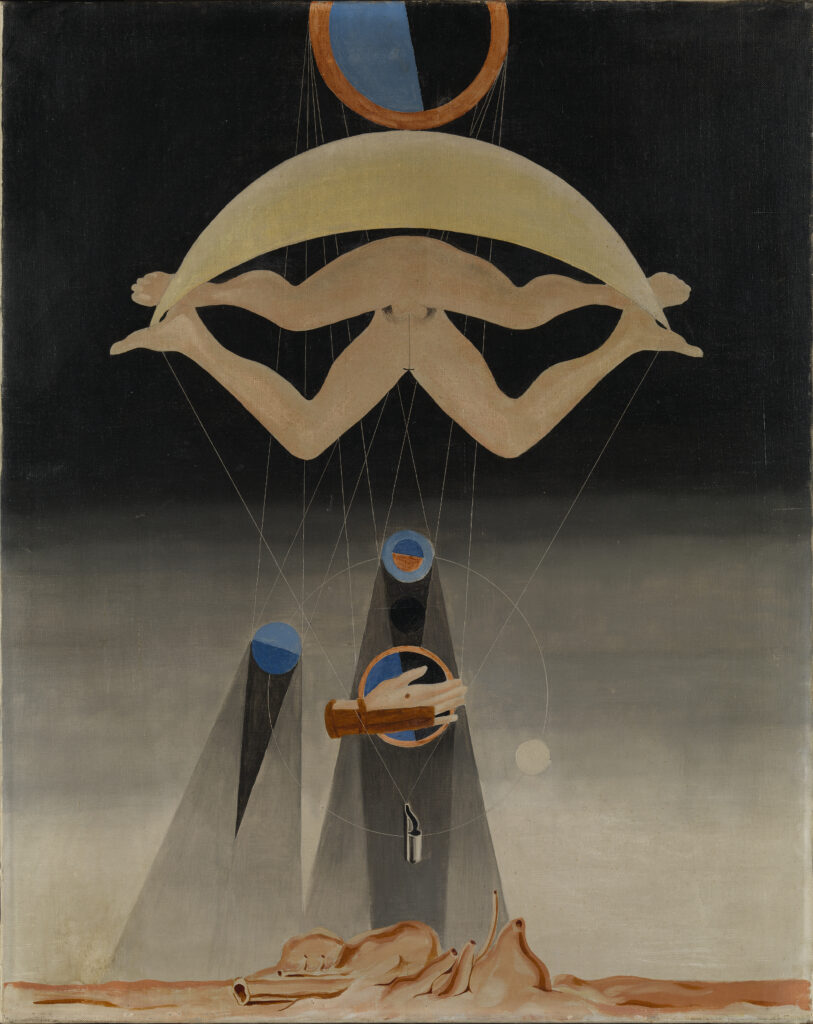

Max Ernst is represented here by Men Shall Know Nothing of This (1923), one of the most iconic works of art of the Surrealist movement (shown below). He actually gifted the painting to Breton, who reproduced it in his 1928 book Nadja. Even though it clearly depicts the geometry of eclipses, the descriptive card at the DMA makes no mention of the astronomical imagery. At the top of the painting there is a mysterious ‘sun’. From it rays descend to circling astral bodies – ‘the earth’ (covered by a disembodied hand) with attendant planets. It is believed the painting was inspired by the delusions of one of Freud’s patients.

Miró, my personal favourite painter of the 20th century, is represented by his 1938 work A Star Caresses the Breast of a Negress. It is based on a poem he wrote in 1936.

Many other prominent and lesser-known artists fill the walls. Salvador Dali has Autumnal Cannibalism (1936), Jackson Pollock has Yellow Islands (1952), and Mark Rothko has a watercolour from 1944. This was a transitional time for him, as his interest in surrealism evolved into his personal style.

The exhibit, which includes several sculptures and a film clip from 1937, is arranged by themes that are fully explained on wall plaques. These include Automatism, Politics, Objects, Desire, and Uncanny Nature.

Instead of just hanging works on a wall, the DMA has given us an innovative experience, with a floor-to-ceiling curved transparent shield-like mirror that transforms reflected images into surrealist shapes (photo below). And as you enter, one is confronted by a giant eye: through the iris one can see a work of surrealist art in the next room.

A truly fascinating look at an art movement that still resonates a century later, this is a rare treat from London. Highly recommended!

Lead photo: Women and Bird in the Moonlight, 1949. Joan Miró. Tate, purchased 1951. © Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2025. Photo: Tate.

Second image: Men Shall Know Nothing of This, 1923. Max Ernst. Tate, purchased 1960. ©

Artists Rights Society. New York/ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Tate.

Third image: The exhibit space. Photo by C. Cunningham

International Surrealism runs thru March 22, 2026.

Visit the website: www.dma.org