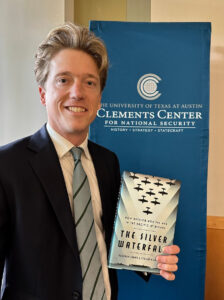

The Silver Waterfall has been written by Brendan Simms and Steven McGregor. McGregor, who gave a talk on the book in Austin (hosted by the Clements Center), is a US Army veteran with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Simms has written two books relating to Hitler, and one on the Battle of Waterloo.

The topic of this book is the dramatic and unexpected reversal of Japanese military aims in World War II. High off their victory in Hawaii in December 1941, their apparent pre-eminence ended just six months later. “On the 4th of June 1942 off Midway Island,” said McGregor, “the U.S. navy ambushed the Japanese striking force and sunk all four of its carriers. The Japanese advance stalled and its navy never recovered.”

But was this just a matter of luck? That is a key question posed by the authors, as the ‘victory’ has consistently been framed in that fashion. In his book Incredible Victory (1967), author Walter Lord wrote “The Americans had no right to win.” And a 1976 film, entitled Midway, the Admiral Nimitz character played by Henry Fonda asks at the end “Were we better than the Japanese or just luckier?”

The Silver Waterfall authors “push back against this view. We stress the importance of skill and training, showing how the pre-war U.S. Navy developed a deadly dive-bomber weapon which came into its own in five legendary minutes.”

The book takes its title from the visual appearance of the attack of the dive bombers on that June day, as the sun glinted off their wings. One observer described it as ‘a beautiful silver waterfall.’

McGregor said that “what’s striking about our story is that it’s actually a battle which is won by the peacetime Navy. Every carrier that served at Midway was commissioned long before the war began. Every pilot who scored a hit on a Japanese carrier earned his wings before Pearl Harbor.”

The book brings the reader into the story in an unconventional way for a narrative about a grand battle: it takes the initial three chapters to explore the background of three individuals who the authors identify as critical to the win at Midway. These are the Engineer, Gustave Henry Heinemann (born in Saginaw, Michigan 1908); the Strategist, Chester Nimitz, born just west of Austin in Fredericksburg in 1885; and the Pilot, Dusty Kleiss from Cofeyville, Kansas in 1916.

McGregor summarized the career of these men. Heinemann “never went to university, he just wants to design airplanes. He designed his first airplane at age 21 and 5 years later enters a competition to produce a dive bomber. He’s working for Douglas Aircraft, and he submits a design which later becomes the SBD: ship-borne dive bomber.” The one used at Midway was the Dauntless. In January 2020 the authors gained access to the Heinmann papers in San Diego at the Air & Space Museum, “which none of the other accounts of the battle had looked into.”

Nimitz entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1901 and graduated in 1905. “He entered the Naval War College in 1922 and here he learned about a new technique of using the aircraft carrier as the capital ship of a circular formation of destroyers and cruisers (previously the battleship was the capital ship). When Nimitz was promoted to become the executive officer of battlefleet on the West coast in 1923, he implements this idea.” After Pearl Harbor he was made Commander of the Pacific Fleet, and while many ships were sunk then, the carriers escaped unscathed. “Nimitz then goes on the offense, launching raids to unsettle the Japanese.”

The enemy, under Admiral Yamamoto, planned to lure the carriers into an ambush at Midway atoll, but this was foiled by U.S. Signals intelligence who learned of this plan in advance, “so Nimitz decides to set a trap of his own, positioning two carrier task forces north-northwest of Midway.” The carriers were 800 feet long and were manned by 2,000 servicemen. Each held 27 fighters, 37 dive bombers, and 15 torpedo bombers. Opposing them were four Japanese carriers with a similar complement of planes.

All the strategy and hardware would have been for naught without skilled and fearless pilots to maneuver the plane and deliver the bomb with great precision to disable or sink a ship. Dusty Kleiss distinguished himself at Midway. “When it’s Kleiss’ turn to dive, he goes through his checkoff list at 20,000 feet so that his plane can operate at sea level in less than 2 minutes once he initiated his dive.”

As he approached one of the enemy carriers, he saw the rear half of the ship in flames 50 feet high, caused by an explosion one of the earlier planes caused by dropping an incendiary bomb. Kleiss remembered that the bow with a big red circle was intact: it was an enormous emblem of the Rising Sun. Kleiss envisioned the position of that red sun 40 seconds hence and aimed at that point. His plane accelerated to 240 knots. He passed 2,500 feet altitude, the recommended release point, but he continued diving. He was so determined to secure a hit he waited until he was at 1,500 feet above ocean. He moved the release lever, releasing his 500-lb. general-purpose bomb. A second later he releases two 100-lb. incendiaries, and pulled up.” Looking back at the carriers, Kleiss said they were “flaming like Kansas straw stacks.” On the carrier he hit, Kleiss saw a catastrophic explosion that scooped out the forward part of the carrier. Its huge elevator was thrown into the air, with parts of ship going up 4,000 feet!” Kleiss went on to hit two other enemy ships that day; in total 3,057 Japanese died in the battle. Kleiss died at age 100 in 2016, and his memoirs appeared in print the following year.

“For Nimitz,” the authors write in the book, “the real victor of the battle was clear: the dive-bomber pilots and their Dauntless planes. Shortly after the battle, he sent Ed Heinemann a private telegram. ‘Thanks for building the SBD. It saves us at Midway.’” The book goes into considerable detail about the battle, in a well-written style that relies on the memoirs by Kleiss and on Japanese accounts that have not yet been presented in English.

While Midway was a great victory for the U.S., the battle statistics more were sobering: the success rate of the planes against the carriers was only 21%. The torpedo bombers were particularly problematic: of the 40 that launched, only five came back. McGregor attributed that in part to the fact the crews never engaged in live-fire drills, which would have revealed tech problems. “The torpedo the Americans used had a propulsion system that wasn’t very strong, it’s detonator was faulty, and the way it moved through the water was impacted by the way the torpedo was deployed. They didn’t realise all this until 1943.”

The book includes 31 pages of notes for the interested reader to explore the original sources. As the first well-balanced account of a critical naval battle, this is a very fine addition to the literature of World War II.

The Silver Waterfall is by Public Affairs. It lists for $30.

www.clementscenter.org