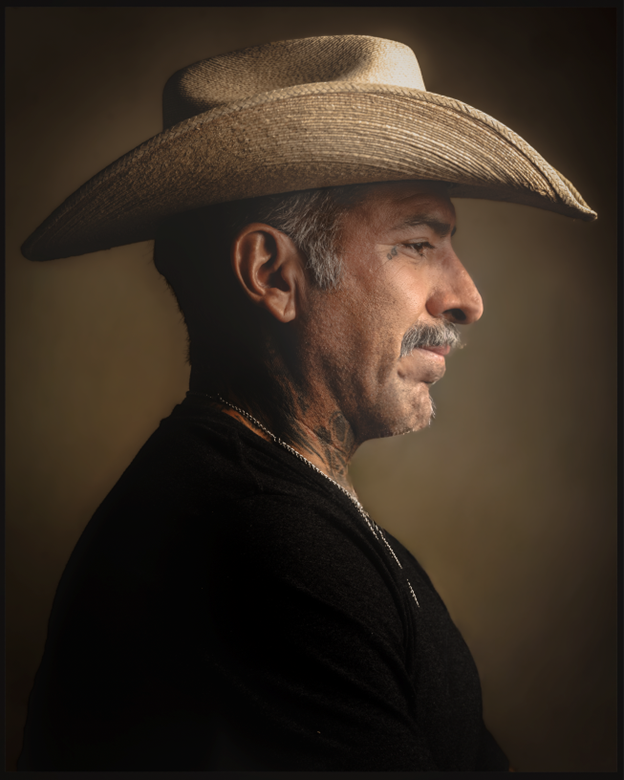

On an afternoon inside a small East Austin space—half studio, half neighborhood hangout—photographer and filmmaker Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon waved a passerby in from the sidewalk. Ten minutes later, the man—Rick, a local gatekeeper with a complicated past—was telling his life story and posing for a portrait that feels equal parts confession and coronation.

“My favorite thing,” Lyon tells me, “is creating a space where someone can be a little vulnerable. If I’m lucky, I can press the button at the right moment, and the picture is really just the document of that moment we share.”

Lyon’s latest series—shot over two and a half weeks as an informal residency—gathers a cross-section of Austin you don’t always see on gallery walls: neighbors, radio hosts, a child of a friend, people who were total strangers until the door opened and a conversation started. It’s exactly the Austin I recognize and miss in equal measure: layered, polyglot, funny, bruised, resilient.

“Every city has its elements,” Lyon says, “but Austin can feel a little segregated. I’m deliberate about including people we don’t always recognize or acknowledge. Everybody has an amazing story. Not everybody gets a safe place to tell it.”

Safety, intimacy, and earned trust are the through lines of Lyon’s life, not just his pictures. Born in Santiago, Chile, he spent early childhood in the Florida Keys before his family landed in Jackson, Mississippi, where he learned English and navigated a social landscape starkly divided into “white folks and Black folks—and then ‘other.’” As one of the few Latino kids around, he often found himself grouped with exchange students and recent immigrants. In Jackson, he says, “outright hostility wasn’t yet focused on Latinos; there simply weren’t enough of them to target.”

That changed in Houston, where, he recalls, “the obvious racism started,” delivered with the blunt vocabulary of schoolyard America: beaner, spic, go back to your country. Lyon shrugs, displaying no bitterness. “I knew who I was. Good parents helped. And seeing so much diversity kept me grounded.”

We bond over the immigrant chameleon’s toolkit: adapt quickly, listen hard, blend when you must, brighten when you can. “It served me well in journalism,” he says. “To show up, to be present, to see.”

Lyon did a stint in Los Angeles teaching tennis—his father was a pro and later a country-club director in Jackson—before New York “chewed me up and spit me out.” In his mid-20s he reset in Austin, committed to school, and eventually chose photojournalism over art—not because he lacked artistry, but because journalism promised “discipline and structure.” He credits Dennis Darling, longtime leader of UT’s photojournalism sequence, as an early compass: “I probably needed the journalism school’s rigor. Dennis was the right person at the right time.”

By the early 2000s—the lumbering dawn of digital news—Lyon was experimenting with short videos and web-native storytelling. The Austin American-Statesman noticed and hired him as a video journalist “before anybody really had video journalists,” he says with a laugh. “We were trying everything: mini-docs, immersive 360 photos, whatever we could hack together. My boss let me play. He protected the idea that we weren’t going to be TV people. Our work was different—more raw, more patient, less formula.”

“Patient” matters here. Lyon has the temperament of a documentarian, not a headline hunter. Yes, there was spot news—hurricanes, plane crashes, sirens—but he prefers the longer stare: people, patterns, the human seams of a city.

After nearly a decade at the paper, KUT/KUTX called. He pitched what a public-media “new media” shop could be: a real photo desk, short-form documentaries, musician profiles, and pop-up music videos (Lyon is a self-described “music junkie”), all in dialogue with the station’s reporting and local culture. “For another eight or nine years,” he says, “we built a multimedia department that felt like a daily—just with radio DNA.”

In parallel, Lyon taught several semesters at UT. The speed of change startled him. “My first class, we’d spend weeks on things a four-year-old could do today. Each semester I had to up my game. The students at the end were infinitely more fluent in digital storytelling than the graduates at the beginning. It was thrilling—and humbling.”

If the newspaper years were about building new muscles for old institutions, the public-radio years introduced a different kind of strain. The pandemic, the George Floyd protests, and a suite of internal DEI struggles took a toll. “One of my staffers caught COVID early, when we didn’t know who would survive. I had sent him to the assignment. That was scary,” Lyon says. Reporting on the protests brought him face-to-face with police firing so-called “less lethal” rounds. “A kid next to me caught a beanbag round. On the other side, protesters were yelling at media, accusing us of feeding images to police. I was in the middle trying to do the thing we’re supposed to do—document what’s in front of us. But I’ve never been a traditional spot-news person. I wanted the long story: the officer’s life, the kid’s life—two human beings colliding in an American moment.” He pauses. “That wasn’t the assignment.”

Then Lyon’s mother died—unrelated to COVID, but during its isolating early months. “Total momma’s boy,” he says softly. “She used to tell me: if you ever put as much energy into yourself as you do into your employers, you’ll be so successful.” He smiles. “I finally listened.” He left the station, went freelance, and doubled down on community arts. He joined the board of Prizer Arts & Letters, and when the space sold, he pitched a nomadic gallery model—pop-ups, collaborations, low overhead, wider reach. After a year spearheading that transition, his formal board tenure is ending, but he plans to keep producing pop-ups with friends: “It’s closer to how I work—scrappy, responsive, generous.”

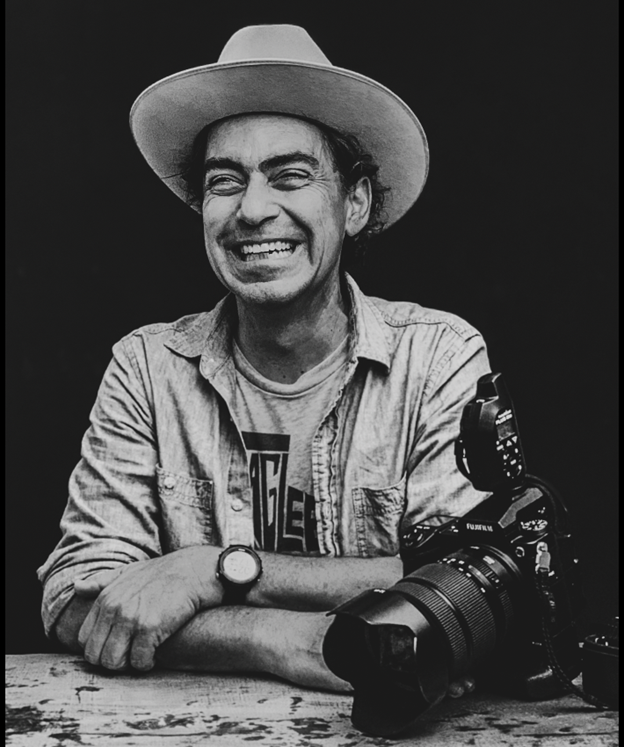

Generous is the right word. Lyon gives sitters their portraits; money, he jokes, will “come from somewhere, I hope.” The portraits themselves have a distinct spine: black-and-white, open shadows, a theatrical stillness that never feels stiff. Some are straight-on; others tilt into the subject’s breath, the quiet between jokes. “I was a shy kid,” he admits. “Still am. Photography lets me make up for missed opportunities with people. A portrait is always an engagement. Always deliberate. I have to be a little vulnerable—goofy, self-deprecating—so the other person can be, too. If the photo is bad, that’s on me. Not them.”

He resists the language of extraction—he is not “taking” anyone’s essence. “I’m trying to create the conditions where someone can reveal something they wouldn’t otherwise reveal.” He points to a woman who had sworn she’d never be photographed. “She’s wonderful but camera-shy. We were fart-joke silly half the time. But then there were these quiet pockets where her ancestral power came through—two or three frames where she’s stoic, centered. That’s the session.”

A quieter tension: immigration status has also shadowed his past few years. Lyon remains a permanent resident, not a citizen, and as the nation’s mood hardens, he’s canceled international travel “because I’ve heard of people not getting back in.” He laughs at himself—ever the journalist, maybe not the most strategic résumé in times like these—but the caution is real. “It’s a challenging time,” he says. “So I keep the work apolitical on the surface. The politics are in who we invite in, who we see.”

Which is to say: the politics are in the door, open.

A walk through his recent show confirms the method. Here is Isla, luminous and inward; Marnie, the radio person who popped in from across the way; the neighbor’s child; Rick from the sidewalk; a young man discussing second chances, the future sharp with both hope and worry. “Each picture has a little story behind it,” Lyon says. “Where we met. What we talked about. What time of day it was. I can look at a frame from twenty years ago and still remember the air.”

His next body of work is already coalescing: a stark, black-and-white bar series—working titles Watering Hole or Barfly—that studies people suspended in mid-conversation with themselves. “Bars are confessionals,” Lyon says. “Bartenders and barbers are pastors. I’m listening.”

Listening is the first craft he learned and the one he refuses to unlearn. It helped him survive as a Chilean kid in the Deep South, helped him sidestep the worst of New York’s churn, helped him build multimedia desks before anyone knew what to call them, and keeps him anchored now—freelancer, teacher, nomadic curator, portraitist—when attention is currency and intimacy is revolt.

“People will tell their story,” Lyon says. “Everybody wants to be heard. But not everybody feels safe enough to do it. That’s my job: build the room. The picture is just proof the room existed.”

Standing in front of the wall of faces, I feel it—the room. It’s not the square of paper. It’s the charge between two humans when the question lands and an answer that sounds like truth rises to meet it. In these pictures, and in the practice behind them, Lyon keeps building that room, one careful hello at a time.

Follow Lyon’s upcoming pop-ups and projects on Instagram @jsanhuezalyon and via his site www.jorgesanhuezalyon.com

lead Photo Credit: Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon

second photo: Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon self-portrait; Photo Credit: Marcelina Kampa