The Museum of Fine Arts Houston is currently hosting a very special exhibit: the finest collected works of one very rich person.

Armand Hammer (1898-1990) made his fortune in oil. He was chief of Occidental Petroleum from 1957 until the end of this life. Among his philanthropic works, he gave 40 million pounds to projects run by Prince (now King) Charles, back in the 1980s. From 1965 until his death he amassed the works that form the basis of the Hammer Museum’s collections.

From the website of the Hammer collection (normally on view at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles), we get an overview of what is being shown here in Houston:

“The Armand Hammer Collection provides an impressive overview of the major movements of nineteenth-century French art, with significant examples of realism, orientalism, the Barbizon school, impressionism, postimpressionism, pointillism, and symbolism by artists such as Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Gustave Moreau, Camille Pissarro, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Portraiture and landscape both figure prominently in the collection, and several artists are represented by more than one work. Moreau’s jewel-like King David (1878) and evocative Salomé Dancing before Herod (1876) are two of the artist’s most renowned works, while Vincent van Gogh is represented by three important paintings, including the remarkable Hospital at Saint-Rémy (1889). European old master paintings include two major works by Rembrandt van Rijn from both the earlier and later periods of the artist’s career, Portrait of a Man Holding a Black Hat (ca. 1637) and Juno (ca. 1662–65), as well as paintings by Titian, Peter Paul Rubens, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. Among the American artists in the collection are George Bellows, Mary Cassatt, Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, and Gilbert Stuart.” Sargent’s over-life-size portrait Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881), one of the most prominent works in the collection, is not in the Houston show.

Certainly the star of this show is the Rembrandt painting of Juno (lead photo), wife of the great god Jupiter, and thus Queen of the Gods. As he is my favourite painter, it was a special treat indeed to see this for the first time. Roughly 300 paintings have been attributed to Rembrandt; I was fortunate to see the large collection of 20 works in the Hermitage (St. Petersburg, Russia), a venue that will likely remain off-limits to foreigners for many years due to the war; and earlier this year I visited the Rembrandt House in Amsterdam. Rembrandt finished his work on this masterpiece just four years before he died, and in financial difficulty. The Juno painting became a bone of contention with his creditors, who wanted the master to do further on it, thus raising its value. Hammer made sure everyone knew he has bought the Juno; it became international news in 1976.

Look at the bottom left of the painting to see the bird associated with Juno: a darkly-coloured peacock is visible. The bird nestles beside a sceptre denoting Juno’s queenly nature. Juno looks at us directly, with her commanding presence guaranteed to dominate any room in which it is displayed. It is joined here by the Black Hat Rembrandt, done almost 30 years earlier than the Juno. While the man faces us, his body is turned to face right. Typical of this period in his works, Rembrandt illuminated the man’s right cheek. His head rests above a bright white lace collar. His rich taffeta costume exhibits a complex geometrical patterning, enhanced by a luminous sheen.

The other three paintings I am showing here are all for the 19th century, and are of a completely different character. The vibrant colours of Wheat Harvest by Emile Bernard (1868-1941), a name known only to art experts. He was friends with three of the greatest artists of the century: Gauguin, van Gogh and Cezanne. Bernard was only 21 when he painted this, and it is infused with iconography that, again, only art experts are familiar with. Wheat is the symbol of the Resurrection, a link made explicit by a cross atop a hill at the upper left. The flat colours of the clothing, the animal and the landscape are so eye-catching, the cross is easily overlooked. It is thought this shows a place in Brittany, France, where Berhard stayed in 1889.

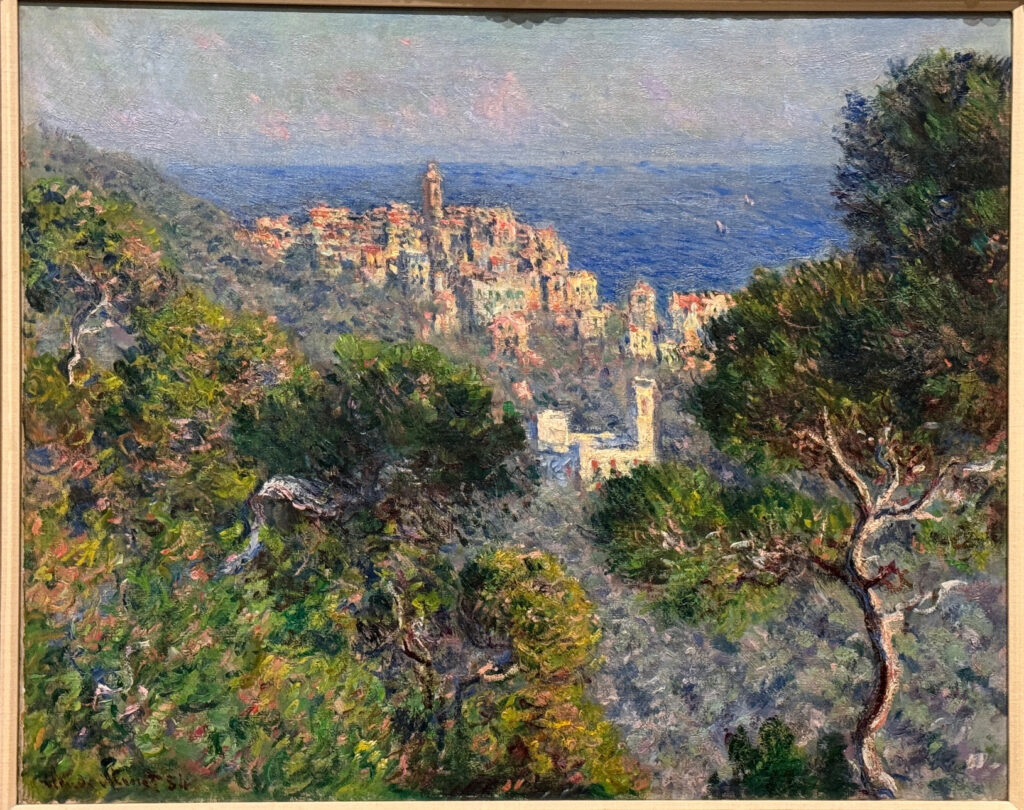

Claude Monet (1840-1926) is also represented here, in his View of Bordighera, a small Italian coastal city near the French border that I passed through earlier this year on my way to Monaco. Monet first visited here in 1883; the following year he returned for what was supposed to be a three-week stay fully dedicated to painting. This short stay ended up lasting three months, during which he painted a series of three views of the city: the painting in the Hammer collection is one of these.

In a letter to his fiancée, Monet wrote that painting in Bordighera “is extremely difficult to do and it is very time-consuming, mostly because the large self-contained motifs are rare. It is too thick with dense foliage, and all you can find are motifs with lots of detail, jumbles terribly difficult to paint, and I, in contrast, am the man of isolated trees and large spaces.” Despite his concerns, Monet succeeded in creating a masterpiece for the ages. With its liberal used of red highlights, the town shimmers as a bright yellow presence against the blue sea beyond. Viewed from a hill, we see the town almost as a mirage. Is it Shangri-La, or perhaps a Moorish town magically transplanted into Italy? Monet raised this little Italian town to a magical space where our imagination can run free.

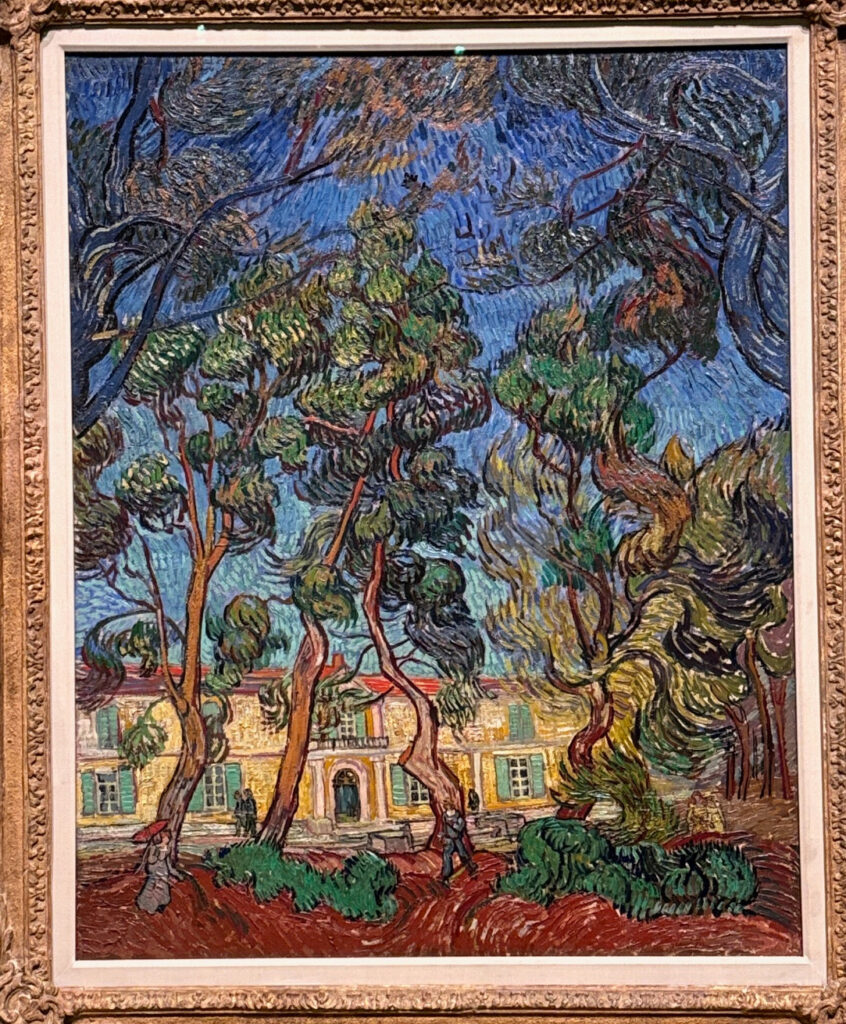

Since the exhibit title includes Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), any viewer of this exhibit will be eager to see what treat awaits from the iconic Dutch master (note that Rembrandt was also Dutch). Hammer gives us Hospital at Saint-Rémy, painted very near the end of van Gogh’s life. Here we see the asylum van Gogh voluntarily entered on May 8, 1889. “I feel happier here with my work than I could be outside,” wrote van Gogh. “By staying here a good long time, I shall have learned regular habits and in the long run the result will be more order in my life.” In this painting we see the trees near the asylum, twisted into fantastic shapes by his imagination. The vibrant palette results in a dynamic expression of his inner life. Another great masterpiece, one of several that visitors to Houston can see now. Highly recommended exhibit!

Photos shown here:

Emile Bernard, Wheat Harvest, 1889

Claude Monet, View of Bordighera, 1884

Vincent van Gogh, Hospital at Saint-Rémy, 1889

Rembrandt van Rijn, Juno, ca. 1662-1665 (Lead photo)

For an extended discussion of the Juno painting, go to this link from the Getty Museum:

and for an article about Hammer’s purchase of Juno, see this link:

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1976/10/2/juno-has-arrived-pno-one-should/

The exhibit runs thru Jan. 21, 2024. Visit the website for more: www.mfah.org