“As intellectual historians have long emphasized, a key question in eighteenth-century philosophy was that of sociability or the extent to which humans were (or could be made) fit for political society. The place afforded to laughter and ridicule within that debate, however, has so far been neglected.”

Anyone who watched President Biden’s State of the Union address in Feb 2023 knows that many unmannered brutes in the party of Lincoln are not fit for political society, so not much has changed since the 1700s. But as we also saw in the days after the presidential address, Pres. Biden used laughter when asked what he thought of the brutish behaviour. He was in fact deploying the laughter of ridicule; a book of 1759 stated that one exhibits such laughter when encountering something “ugly, deformed, improper, indecent, unfitting, and indecorous.” Yes, we are talking about you, MTG! What could be more ugly and deformed than someone who supports treasonous acts?

Ross Carroll, a senior lecturer in political theory at the University of Exeter, draws attention to that book from 1759 early in his very fine study that explores the place of laughter and ridicule in England and Scotland. He does not, however, confine his focus to the 1700s, stating at the outset that returning to the 18th century debate on ridicule can inform the body politic today. It will, he says, “speak to the disagreement between those who see forms of speech such as sarcasm, satire and mockery as essential to a healthy politics and those who fear them irrational, trivializing or abusive.”

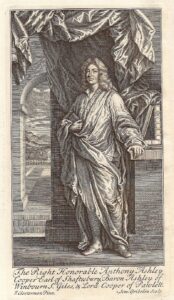

He explores the premise, promoted by the Earl of Shaftesbury, that “it was from contempt that ridicule derived both its danger and its practical efficacy as an instrument of enlightenment.” The writings of Shaftesbury, the author explains, were central to the following generation of philosophers. Here we find Bernard Mandeville (a champion of Shaftesbury) and Francis Hutcheson (his most trenchant critic). It is from their duelling pens that “the significance of ridicule to the debate on sociability comes truly into focus.” Shaftesbury “refused to draw the sting out of ridicule by equating it with affability or good-natured raillery. Instead, Shaftesbury offered a multi-layered defence of ridicule, one that made full and unapologetic use of its corrosive potential.”

I found Carroll’s look at the way Shaftesbury interpreted the ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes to be particularly insightful. Diogenes was accosted by a reproacher, who said he (Diogenes) did not believe in the Gods. Diogenes retorts “How can I not believe in the Gods when I find you wretched to them?” For Shaftesbury, Diogenes not only deflected the accusation with “a witty rebuff, but rather turned the accusation back on his reproacher. He, Diogenes, was the true theist; his accuser was the one guilty of impiety.” But Shaftesbury was frustrated that the ‘Divine Facetiousness’ of Diogenes had been so obscured by his time that “no one now sees or understands” it. Carroll argues that despite this obstacle, the Earl “attempted to play the part of Diogenes in his own religious critique.” His critics howled when Shaftesbury “implied that Jesus lacked something that Socrates possessed.”

Carroll poses a stark question about the Earl’s intent. “If Shaftesbury used ridicule as a Cynic shock tactic then what alternative way of thinking about religion was he trying to edge his readers towards?” To replace the Christian penchant for committing all manner of atrocities, the Earl quite simply thought “a good-humoured religion” based on a belief in a benevolent God was the path forward, and in that he was certainly correct. Unfortunately, by his death in 1713 Shaftesbury “had been given every reason to believe” he had not won the culture war. Alas, ridicule did not “replace persecution as a response to religious enthusiasm.”

In the 1750s, David Hume also engaged with clerical issues, taking delight in ridiculing ministers. In a letter to a friend, Hume writes that priests differ from other professions because they “are conscious they are really ridiculous.” Carroll tells us the letter “recalled Shaftesbury’s argument that the test of ridicule could distinguish those who are ‘really ridiculous’ from those who merely happen to be mocked. Hume’s stance on the relationship between humour and hypocrisy was more complex that this squib might suggest, however. Unlike Shaftesbury he appreciated how good humour could not only expose hypocrisy but enable it as well.”

Also in the 1750s, the writings of Shaftesbury loomed large in Scotland. There, George Campbell participated “in a long-running discussion in Aberdeen over how Shaftesbury’s teachings might be used to refine Scottish manners and taste.” The stage had been set in the 1740s by George Turnbull, “who defended Shaftsbury’s doctrine of natural sociability and held up the Earl’s style as an example of how Mandeville and other modern Epicureans might best be countered.” (Even though Mandeville generally stood with Shaftesbury, he concluded that religion could never be the “proper object of ridicule.”)

A decade later, Campbell cited the same passage from Aristotle’s Rhetoric that Shaftesbury used, leading Campbell to recommend that speakers use the “aid of laughter and contempt to diminish, or even quite undo, the unfriendly emotions that have been raised in the minds of the hearers.” Carroll discerned that in “emphasizing the place of ridicule in persuasion, Campbell seemed to divorce it entirely from philosophical inquiry.”

The subject of ridicule was an active one in the time of the French revolution. In the 1780s, Mary Woolstonecraft exhibited “little faith in ridicule’s truth-revealing capacities…The indirectness of ridicule made it conducive to the kind of hypocrisy she identified with aristocratic culture.” French courtiers, she noted, “appear polite” at the “very moment they are ridiculing a person.” Far from being a test of the truth, Carroll writes, “ridicule was a tool of deception wielded by backstabbers who tried to gain the confidence of others only to make their fall more exquisite.”

In this review I have mostly confined myself to tracing one thread of a multi-stranded argument that Carroll weaves with great scholarship. While looking at many other philosophers (including Ramsay, Beattie, Geddes, Montesquieu and Hobbes) and their engagement with ridicule and laughter, he presents us with a rich and fascinating look at how 18th century discourse was framed and understood in many areas including the fight against slavery. A most valuable study, which must be engaged with in all future studies of the Enlightenment.

The author makes liberal use of footnotes that often consume half of the printed page; each chapter has more than 100 of them. The book is completed by a 21-page Bibliography and an excellent 12-page Index.

Unfortunately, the book was not well proofread. I found the following errors: “to his to son” on pg. 10; “instead would instead” on Pg 70; on pg. 82, the word ‘to’ is missing in “Tempted to mock”; on pg. 121, the word ‘to’ is missing in “similar to that of”; “not to be seen not as” pg. 129; on pg. 133, the word “a” is missing in “by a poet”; “a shared a” on pg. 152.

Uncivil Mirth: Ridicule in Enlightenment Britain is by Princeton University Press. It lists for $35.

Image: The Earl of Shaftesbury