While not well known amongst the public of American anymore, Winslow Homer was considered one of this country’s great artists at his death in 1910. It is safe to say that aside from those very much tuned into the artistic scene, he is virtually unknown in Europe. Not a single museum/art gallery in England holds any of his works.

Thus, the current exhibit in London is of the utmost importance, giving him the brightest possible spotlight by a showing in the National Gallery itself. I can’t recommend the accompanying catalogue by Yale highly enough. The text is written by Christine Riding, Christopher Riopelle and Chiara di Stefano, all at the National Gallery. Their analysis is quite understandable to anyone interested in art, so you don’t need an art degree to glean a valuable knowledge of Homer’s life and works.

Various American galleries have loaned their finest Homer paintings for this landmark exhibit: foremost is the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Others include Portland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the National Gallery in Wash DC, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Some are even from private collections.

This is a show rich in highlights, too many to cover in this review. I’ll start with the lead photo, Undertow, dated to 1886. In his essay, Riopelle tells us the background of the painting. “At Atlantic City, New Jersey, he witnessed a shocking event: two female bathers caught in the undertow and in danger of drowning.” Two brave male bathers saved them. “After three years of distillation,” Homer painted Undertow, “one of his most timeless, austere, frieze-like compositions, as if a bas-relief on an ancient Greek pediment. It is also a rare example of heroic nudity in his work, and it has an erotic charge.” Relating it to poetry, Riopelle sees here Wordworth’s ‘emotion recollected in tranquility.’

In the same vein of heroism, Homer painted The Life Line, a novelty in American art. In her essay, Riding writes that it “was admired by critics and first viewers as much for its formal innovation and painterly virtuosity as for the pleasingly heroic modernity of its subject.” The modernity here being the fact of the lifesaving “that was made possible only through a recent technological innovation: the breeches buoy. Secured to both the ship and the shore (or ship to ship), it permitted stranded passengers to traverse the sea to safety by means of a pulley.” This makes the work of interest not only to art historians but scholars of 19th century technology.

Towards the end of his career, Homer either reduced human figures to a what Di Stefano describes as “tiny, insignificant presences facing the power of nature,” or eliminated the human element entirely. Such was the case in Northeaster, 1895. A former curator of the Met wrote that “in the opinion of many people, Northeaster is Homer’s masterpiece. Certainly one can rarely find so vigorously expressed the dynamic energy and weight of moving water.”

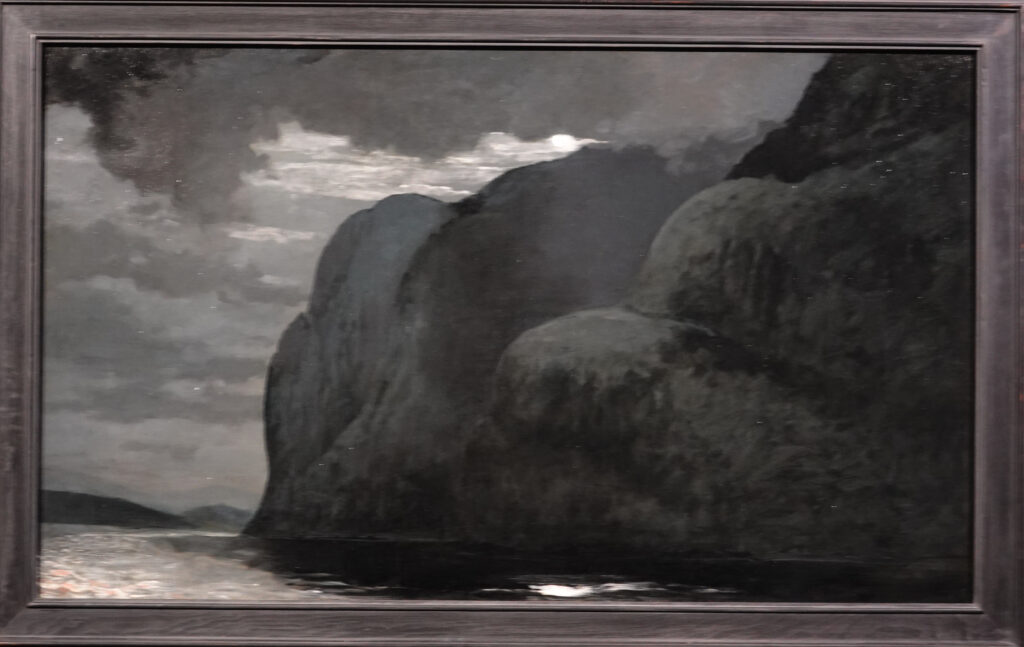

For all that, the painting that impressed me most was a view he painted of Canada’s east coast. The catalogue says little of it, so I quote from the description given in the exhibition. “Inspired by memories of Canadian fishing trips he had been taking with his brother Charles since 1893, Homer shows the dramatic outcropping of rocks in three plateaus (Cape Trinity) on the Saguenay River, north of Quebec City. The sombre, mysterious landscape comes close to abstraction and carries striking psychological weight.” That’s an understatement! This moonlit scene is the most powerful I have ever seen. My photograph here shows a lot more detail than the one in the catalogue, which is largely just black on the right. A brooding masterwork that deserves close attention, and it begs the question as to what other depictions of Canada he painted. This topic is not addressed in the exhibit or catalogue.

The career of Homer went through several phases. The ones I found least satisfying are the paintings based on his Bermuda and Caribbean trips. Most of the ones shown are dominated by palm trees and tranquil water, the sort of thing modern artists sell to tourists. The one exception is another moonlit scene, Searchlight on Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba (1902). Stung by criticism of this work, Homer wrote it “is not intended to be ‘beautiful’. There are certain things (unfortunately for critics) that are stern facts but are worth recording as a matter of history as in this case.” The proximate cause of the painting was a U.S. naval blockage of Santiago in 1898. The navy shone a powerful searchlight on the entrance to the harbour, preventing the Spanish army from escaping. This military work harkens back to Homer’s early work as an artist during the American Civil War.

Several works on display depict women in heroic stances, as they go about their daily lives in the midst of elemental forces they cannot control, but seem to defy. And the time Homer spent in England, in 1881, inspired many works that he created upon returning to America. His studio still stands, and can be toured in Maine.

An exhibit of intensity, this one should not be missed by anyone visiting London.

Photo credits: Undertow (1886). Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Acquired by the Institute in 1924.

The Life Line (1884). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Acquired 1924.

Northeaster (1901). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Acquired 1910.

Cape Trinity, Saguenay River, Moonlight (1904). Myron Kunin Collection of American Art, Minneapolis. Acquired 1986.

Winslow Homer: Force of Nature is on view thru Jan. 8, 2023. The 127-page softcover catalogue (with 85 colour illustrations) is published by Yale University Press, and lists for $25. Colour reproduction is excellent, but there is no index for what pages a particular painting is discussed on. For example, Undertow is shown on page 76, but analysed on page 29.