The built environment is something we often take for granted. For example, if you were born in London anytime in the last century, the Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace would be seemingly timeless landmarks. But if you went back to London 200 years ago, neither building we admire now would be there.

So it was in ancient Greece. The Parthenon has been a landmark for more than 2,000 years, but it wasn’t always there. What was on the Acropolis before the Parthenon, and who built those earlier structures? And how was it all mediated by the parallel construction of Athenian democracy? That is the subject of this fascinating book by Jessica Paga, Assistant Professor of Classical Studies at the College of William & Mary in Virginia.

Sweeping political reforms (instituted by a man named Kleisthenes) in Athens in 506-505BCE triggered a construction boom in Athens. One aspect of the success of these reforms was a military campaign that greatly expanded the control it had on surrounding territory. “Taken together,” Paga writes, “they represent a remarkable feat and are a testament to the flourishing of the new political regime inaugurated by the reforms in an incredibly brief amount of time.” The span she studies most closely lasted 50 years.

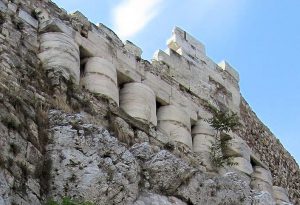

Paga identifies three monumental temples built on the Acropolis between 570 and 480 BCE: first, the Bluebeard Temple (570-560), the Old Athena Temple (500) and the Old Parthenon (begun in 490). This constituted what historians call the Archaic Acropolis. The year 480 is critical as that is when the Persians invaded, and destroyed much of the Acropolis. Construction of the Parthenon we see the ruins of today lasted from 447 to 438, after Athens had recovered from the Persian catastrophe; parts of the Old Parthenon can still be seen today, as shown in the photo with this review.

These were not merely buildings. “They also served to structure those events and preserve, in their siting and ornamentation, the community’s memory.” Not all those memories were good ones. The Acropolis was occupied by Spartans. Even worse, the Spartan general Kleomenes “transgressed when he went against the direct sacred prohibition of the priestess, entering the Bluebeard Temple during the siege in 508/7.” This pollution of one of Athens’ most sacred spaces sparked a move that we can scarcely imagine today. Instead of ritually cleansing the temple, the Athenians dismantled it after the Spartans departed! So it has not just been the ravages of time that have us little of the Archaic Acropolis to look at now; the Athenians themselves were responsible for some of the destruction.

The author is just as insightful in her macro-view of things as the micro-view of each individual building project. This is evident in her study of the Agora area, and its relationship to the Acropolis. While the latter is where worship took place, the business and commerce of state was at the Agora. “The Oul Bouleuterion can be considered the architectural symbol par excellence of the nascent political order brought about by the Kleisthenic reforms,” she writes. It was the 500-member Boule that was the prime representative body of Athens. The hypostyle hall appears here for the first time in the Greek world; its open square plan with flexible seating arrangements “certainly contributed to its success and continued popularity…It’s lack of columnar pediments meant everyone could see everyone else.” Thus the Boule was able to function in a space that facilitated deliberation and fostered a sense of accountability, “concepts vital for the political regime.” Its façade faced south, encouraging access from the Agora and “thereby fully integrating the structure into the rest of the civic space.” The use of the Doric order in this monumental government building, until then used only for sacred temples, “only accentuates how radical a building it was.” From the forecourt of the Acropolis, one could see the Agora 900 meters away, “a view that would have encouraged the ancient worshipper to ponder the relationship between these two spheres of government.”

Paga also tells us of the costs of construction, and materials used. As an example, I cite the monumental Temple to Zeus begun in Athens in 520 BCE. It was intended to be twice the size of the Bluebeard, some 107 x 41 metres. “The foundations are made of Acropolis and Kara limestone, but in this case used and jointed together.” Some elements employed “softer limestone where double T-clamps were employed throughout.” The nearly exclusive use of limestone in temple construction in Athens (with some details set in marble) contrasts with later construction in Rome. Research published in 2021 (in the Journal of the American Ceramic Society) detail the use of concrete in the tomb of Caecilia Metella in Rome. By using volcanic tephra in the mortar to bind together large chunks of brick and lava aggregate, the tomb has survived 2200 years. Concrete used in modern construction is lucky to last 50 years without structural cracking, a testament once again to ancient wisdom.

Even though the Athenians did not use concrete for these temples, the terminology we derive from our Roman heritage informs Paga’s analysis. “The confluence of construction projects in the area of the Agora shows how the new political regime actively sought to define and concretize itself in monumental visual terms.” A key insight she provides is that all this was mediated by “an overarching building project instantiated by the new political regime.” Unlike the New Parthenon, no one name can be assigned to this earlier project. Rather, it was voted on by the populace as a whole, thus becoming a literal building-block of democracy. This was not only in Athens but in its surrounding territories, known as demes. “In total, as many as 23 distinct monumental structures” were built between 508 and 480, “representative of large expenditures on money, resources and labor.” The “unexpected moment of victory” in 506, when Athens defeated a combined force of Greek states led by Sparta, “was also concretized in the demes.”

The author deftly weaves a multi-dimensional look at ancient Athens here. While it is an academic study, her prose is such that this does not weigh heavily, making the book quite readable for anyone. An important book for our understanding of not only the political order but the buildings that were the outward face of Athens in the Archaic period, this will be a valuable addition to any library of Classical studies.

Building Democracy in late Archaic Athens is $74 by Oxford University Press

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons