When Gustav Holst composed The Planets in 1916, the Great War was raging, which surely induced him to open his symphonic suite with Mars, The Bringer of War. The Red planet had long been associated with the god of War, so this was no surprise. The real surprise is that Holst was not particularly interested in the actual study of Mars (or the other planets) as revealed by telescopes. His composition was motivated by the astrological and alchemical aspects of the planets.

Thus, the marriage of NASA spacecraft imagery, shown on the big screen above the Austin Symphony Orchestra – while pleasing to the modern eye – is actually incongruent with the music of Holst. As a planetary scientist myself, I am all in favour of spacecraft imagery being shown to the public, but such imagery has no visceral connexion with Holst’s music. (The imagery is courtesy of a project by the Houston Symphony).

Nonetheless The Planets can be thought of as the grandfather of modern music that really does combine art and science. Due out in December is an electronic audio-visual album made entirely by the exploration of a gravitational singularity. Or, to put it another way, turning black holes into music. It is being done by Dr. Valery Vermeulen, who has a PhD in pure mathematics and an MA in music production. Data for the album was gathered by colleagues of the late Stephen Hawking. If you can’t wait for that, there is always the new album by Coldplay, Music of the Spheres, developed around a sci-fi concept of a distant solar system. The single from the album is My Universe.

Nonetheless The Planets can be thought of as the grandfather of modern music that really does combine art and science. Due out in December is an electronic audio-visual album made entirely by the exploration of a gravitational singularity. Or, to put it another way, turning black holes into music. It is being done by Dr. Valery Vermeulen, who has a PhD in pure mathematics and an MA in music production. Data for the album was gathered by colleagues of the late Stephen Hawking. If you can’t wait for that, there is always the new album by Coldplay, Music of the Spheres, developed around a sci-fi concept of a distant solar system. The single from the album is My Universe.

Whatever your take on the subject is, it was a delight to not only see Saturn through a 16-inch telescope set up on the Mezzanine level of the Long Center, but to hear Saturn: The Bringer of Old Age, which Holst regarded as the best of his 7-movement composition. There were many chuckles in the audience as this movement began, as the vast majority of the audience was over 60.

The program opened with another Holst composition, A Fugal Overture which was composed in 1922. In just over four minutes it transitions from a sprightly opening to emphatic brass notes that herald dulcet tones from the strings. It all has a madcap ending, and was used by Holst as the overture to his opera The Perfect Fool.

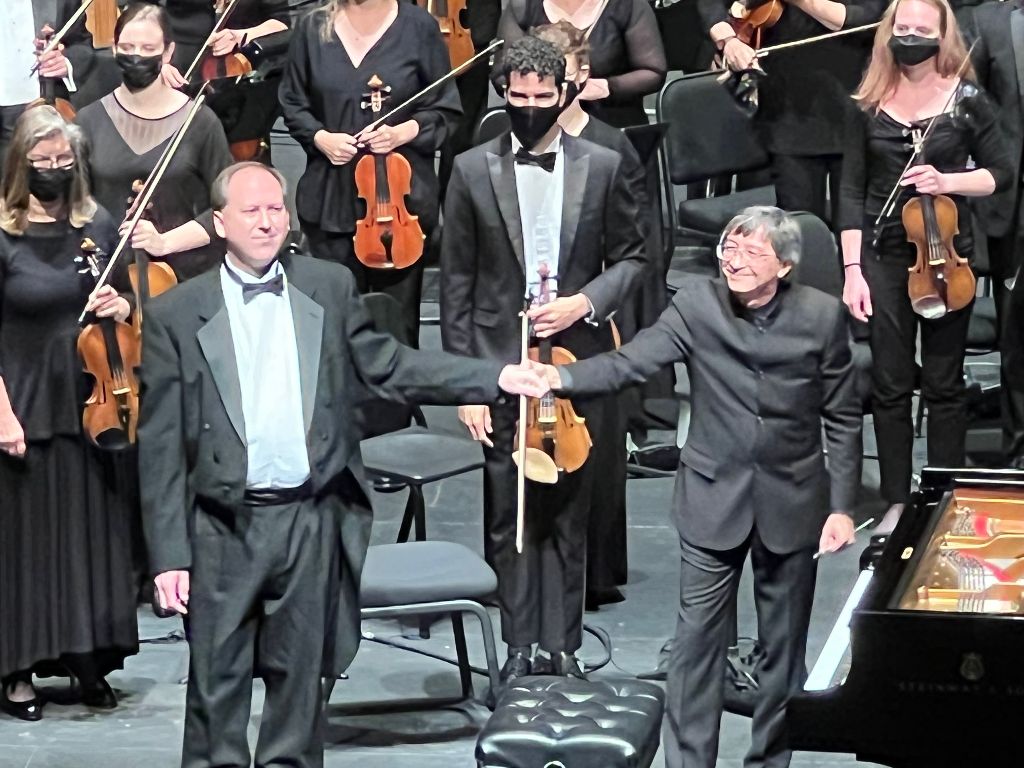

Guest soloist for the evening was Dr. Christopher Atzinger, one of America’s most noted pianists who holds a degree from the University of Texas right here in Austin. He gave an outing to one of classical music’s most-loved piano concertos. First composed by Edvard Grieg in 1868, the Concerto in A minor begins with the famous piano chords, followed by lush strings. A gentle but insistent piano then becomes quite strident, leading the orchestra to reprise the opening melody much louder than before. The solo piano then continues the melody with ever greater insistence as it literally takes over the stage, seemingly silencing the orchestra by its sheer force. When it begins again, the orchestra is very subdued, hesitant to even make its presence known in the face of such power. A delicate passage as fragile as crystal ends that movement. The next movement begins with a whirling passage by the piano, matched by a frenzied orchestral outburst. This gave Atzinger the opportunity to shine in a masterful piano passage, replaced a moment later by a trenchant string passage that reins in the piano, ending in a full stop of all instruments. The concerto resumes briefly before a final display of artistic grandeur.

The concert will be repeated tonight, Oct 16, 2021. Visit www.austinsymphony.org for tickets to this marvellous performance, under the baton of Peter Bay.

Lead photo by C. Cunningham.