I do not think Harold Bloom believed in immortality, only long life (he died at age 89 in 2019). What he called poetic immortality was merely extreme longevity, for even Shakespeare will lose literary relevance when the last human being closes his eyes forever, “and the world is uncreated”. In his last and great work, Take Arms Against A Sea Of Troubles, he frankly admits that for him, “Shakespeare has replaced God”. Unwilling as he was to believe in Yeshua as the Word of God, (which consistently baffles me, for no other story of religious or secular literature gives such imaginative justification for the practice of poetry), Dr. Bloom was equally unwilling to surrender at least the idea of a personal God, and found his “Christ” in Walt Whitman. Walt is certainly the poet of the Western Tradition closest to becoming his words made flesh; Like Beethoven with his music, I have always felt that Whitman could (nearly) re-assume his physical existence from the very lines of his poems, which is, in the fullest literary sense, incarnational. This review is not meant to be comprehensive, and indeed I think it hardly could be, even if I tried. Bloom is too capacious a thinker. Furthermore, I have always been uncomfortable dallying in the mental shadows of those whose intellects are larger than my own.

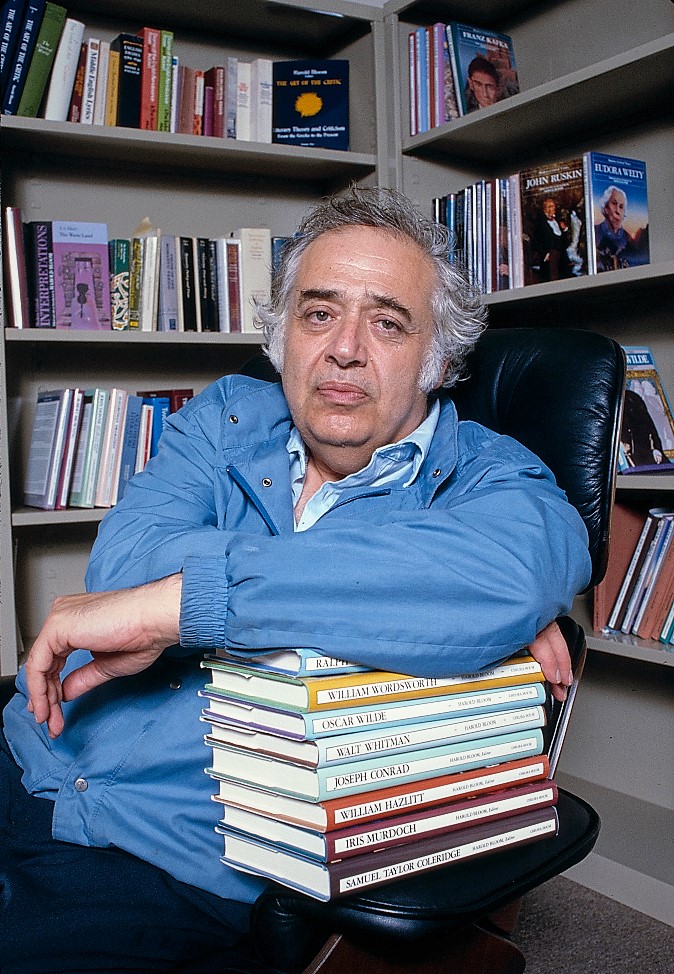

The book contains sixteen chapters, each one of which is focused on one of Dr. Bloom’s favorite authors. Not surprisingly, they are all poets (Shelley, Lord Byron, Yeats, Lawrence, Milton, Blake, Shakespeare, Frost, Whitman, Crane, Dante, Browning, Keats, Wordsworth, Tennyson, Stevens, and in passing, innumerable others). In several of those chapters, two poets are taken at once, and the mutual influence they exerted over each other, over their society, over literature, etc., are all examined. Having read everything, he is one of the few critics who can connect everything. I found his chapters on Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, and his two chapters on Shakespeare to be the most enjoyable, perhaps because no cynicism has permeated his readings of those three writers. His awareness that his own longevity, at least physical longevity, is fading is overwhelming; he mentions it constantly. He says that in his old age, he turns (though one gets the sense that he rather flees) more and more exclusively to Whitman and Shakespeare, who are the two poets whom he puts beyond the archaicism of any age. I myself would add William Blake, but I fear Dr. Bloom would not agree. He always suggested (actually rather conventionally) that Milton was the greater poet of the two, which, for the life of me, I cannot comprehend.

I was surprised that there appeared no chapter on Emily Dickinson, yet one on Robert Frost. Being myself a great admirer of Frost, I had always felt before when reading Dr. Bloom that Dickinson was more important for him. There are certainly some things about Dr. Bloom that I will never understand. His reading of the Gospels, especially the Gospel of Mark, was atrocious, and sometimes, I think, deliberately so. Taking up on the theme that only the daemons of Mark’s Gospel consistently know Yeshua for Who He is, Dr. Bloom suggests that only the diabolical in us can recognize the divine. Blake would have smiled to hear such an observation, but St. Mark would have frowned. I myself find nothing more significant in it than the idea that even Satan and his host were once intimate with God, and like all people living through hell, are pleased (for want of a better word) to meet and ruminate with acquaintances from happier times. Proudly a Bardolator, I still maintain that the Yeshua of the Gospels is the only character to surpass the infinity of Hamlet’s personality and consciousness.

Harold Bloom was the modern era’s greatest defender of literary morality, though he himself would probably revolt at that phrase, always adamant that he did not seek any code of right or wrong from his reading of literature. The most piercing and valuable elucidator of Shakespeare, he himself possessed a mind and imagination of epic proportions. Just as I read Nietzsche as a poet rather than a philosopher, I read Harold Bloom as a poet rather than a literary critic. His insights never cease, crowding upon each other in each new sentence, and like a poet, he can suggest entire universes with simply a phrase (for instance, his observation that “The mind is an activity”). Though I myself have a hysterical and poetic, and therefore hyperbolic nature, I do not shy from calling him the greatest reader and writer on literature of the past four hundred years, surpassing even Hazlitt (who, despite Dr. Bloom’s insistence, was a greater critic than Dr. Johnson). I do believe in poetic immortality, and not merely poetic longevity, and I think that somewhere, in the vastness that is outside this universe, and that our greatest poets entered into even while on this earth, Harold Bloom’s ghost sits still and mutters the last lines of the Song of Myself: “I stop somewhere, waiting for you”.

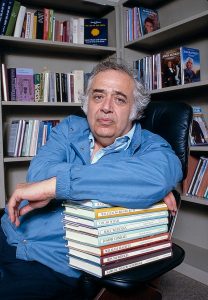

Harold Bloom was the Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University.

Take Arms Against A Sea Of Troubles is $35 from Yale Univ. Press.