Pianist Orli Shaham was likening Brahms’ Piano Concerto no. 2 to a mountain expedition in remarks at Austin’s Long Center. As an international pianist of high repute, she was able to scale the heights of the concerto without using an oxygen tank.

She said the first movement of the 47-minute long concerto from 1881 “is longer than some complete concertos.” It begins with a solo French horn, which for Brahms was a symbol of his father who was an expert on that instrument. Shaham said the motif embodied by the horn “is put through several emotional lenses. The movement runs a gamut of feeling.” It also has a special place in the canon of classical music. While Beethoven used the first notes of his Ninth Symphony in various guises, Brahms takes such “virtuosity beyond what it had been before. He takes the concept as far as it will go.”

A few minutes after Shaham, backed by the Austin Symphony Orchestra, began the first movement, she heralded a new thematic element with a glissando. A stern passage on the piano leads to a crescendo immediately picked up by the orchestra which plays furiously for a minute as if caught up in a passing storm. Lightning flashes from the piano to illuminate the dark landscape created by the orchestra. Just as a few stray sunbeams appear Shaham evoked a delicate rainfall. As the grand first movement ends we find ourselves in a sylvan glade, still trembling a bit at the power of the fast-moving storm we just survived. As Shaham forewarned us, the movement is “a mix of serenity and high drama.”

This storm of emotions is revisited in the second movement. A loud and powerful melody by the orchestra seems to diminish the role of the piano which reasserts itself in the last portion. The third movement begins with a charming melody as Brahms allows the cello to take the lead. Once this tender introduction concludes the piano responds with a series of chords of charming delicacy. The subtle tonalities here are a homage to Schumann, who was such a major influence on Brahms’ first piano concerto. I found the music here to possess a quality best expressed in pre-Raphaelite paintings that influenced such composers as Mendelssohn, Grieg and Delius.

Opening the concert was a five-minute composition by Paul Novak, who won the Butler Texas Young Composers Competition in 2017. He explained On Buoyancy “is inspired by the ocean,” particularly by the Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996). “In his aesthetic philosophy there was a sea of modality between Japanese and Western music.” While some in the audience thought Novak’s piece “lacked cohesiveness,” and were confused by the pings that seemed to be like echo-sounding underwater sounds, it did evoke for me the sense of floating in a primeval sea. Just the sort of sounds that might go through your head if you were tossed about in a chamber hovering just below the surface. Buoyancy was composed three years ago when he was 17.

Those who want to explore the theme of the sea in Takemitsu’s work should listen to his 11-minute 1981 work Toward the Sea, available on YouTube.

Website for future Austin concerts: austinsymphony.org

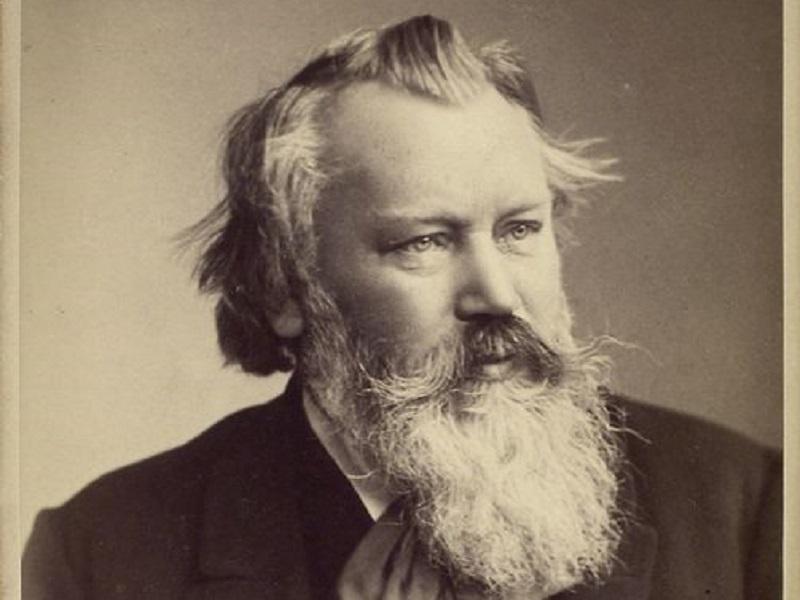

Photo of Mr. Novak by Dr. C. Cunningham