Virgil hailed him as the greatest part of his fame. He was the “living personification of the marvellous,” and a “central enhancing embellishment” of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus. And yet we know little of who Maecenas really was.

This book by Emily Gowers (Univ. of Cambridge) is the most in-depth study ever published on the mercurial figure at the heart of power in the early years of the Roman Empire. As the patron of the arts for the Emperor, Maecenas held a unique place in the Roman world. He was, in fact, Rome’s patron. Living from 68 BCE until 8 CE, he witnessed the rise of Julius Caesar, the fall of the Roman Republic, and the ascent to ultimate power of Caesar’s nephew Octavian. Once he became princeps of Rome, Octavian became Augustus, from whence our month of August derives its name, just as July derives from Julius. These great figures from two thousand years ago revisit us every year.

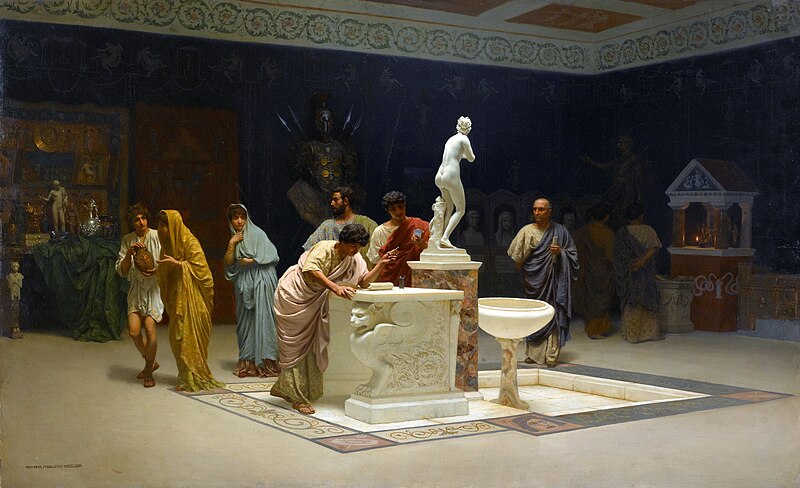

But of Maecenas himself, Gowers writes, “We will never know whether Maecenas was fat or thin, tall or short, fair or dark. The focus in antiquity was not on his face but on his style.” Chapter one offers several illustrations (none in colour, unfortunately). One of these, shown with this review, best exemplifies what historians have to deal with. It is an 1890 painting by Stefan Bakalowicz, and its title is In Maecenas’ Reception Room. We see a rich room with a mosaic floor and sculptures, a marble table, a suit of armour with 4 spears, and a shrine at right. There are 9 figures in the painting, but none of them are the patron himself. His presence is everywhere, but he is elsewhere. As Gowers writes, “Something beautiful, important and valuable is going on in the next room. The desired object is kept out of reach; the mystification is the message.” I think she could have elaborated further on this painting and others, some of which do depict him, although these representations are entirely fictional.

So, who or what was he? Chapter 2 has a series of provocatively-titled sections that attempt to answer this: Patron as god, king, master, host, mistress. Apparently, Maecenas was all of these, and he is said to have been an Etruscan outsider, not a Roman at all! He was much loved by poets in particular. Horace speaks of him a fair bit (seven times): “by turns he plays ruler, drinking partner, surrogate lover, critical audience and intimate friend.” And the greatest of all, Virgil, wrote of him: “Without you nothing lofty can be launched.” Virgil’s Georgics “was written for Maecenus because he had intervened to stop a soldier killing Virgil in a violent agricultural dispute.” It is related that Virgil read the Georgics out loud to Octavian, but after 4 days his voice gave out, at which point Maecenas continued reading the poem to the future Emperor. In the Georgics, “Virgil casts Maecenas as different versions, Greek, Roman and Persian, of the ‘great lord’ in relation to the land: the urban owner who visits his estate to hunt or celebrate a festival, a tutelary nature god and a king prepared to get his hands dirty by planting trees.” As for land, “Maecenas was no average landlord. Until Octavian returned from Greece in 29 BCE, he was charged with the administration of Rome and Italy.” Truly a man for all seasons!

Gowers does far more than examine what was written in ancient times on this prototype of a grand patron. She quotes from a 1680 book by Jean Puget de La Serre: “Augustus loved Maecenas because Maecenas made Augustus loved.” Gowers identified 17th century France as “a golden age and place for Maecenas’ afterlife. He represented a historical figurehead for contemporary royal counsellors and a focus for more abstract political reflection.” Pierre Perrin was clearly trying to get something from the patronage of the famous Mazarin, the royal deputy of King Louis XIII, when he wrote this: “Is our monarch not a nascent Augustus, already the most august of kings? And your eminence, sir, are you not a faithful Maecenas, like him a Roman, like him the most grand and the most cherished minister?”

Visitors to Rome now can actually get quite close to Maecenas. “Somewhere under Termini station lies the ancient footprint of Maecenas’ Esquiline estate. On Maecenas’ death it passed to the emperors.” The famous sculpture Laocoön was found in the vicinity in 1506. Was it in his garden, which has retained a special place in history as a “calm and rarified environment?” Virgil is said to have lived near the gardens, and Horace was buried there, beside Maecenas.

Gowers brings the richness of all this alive for the reader, in a book that Maecenas himself would have welcomed into his library.

Emily Gowers is professor of Latin literature and a fellow of St John’s College at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of The Loaded Table: Representations of Food in Roman Literature and the editor of Horace: Satires Book I.

Rome’s Patron: The Lives and Afterlives of Maecenas is by Princeton University Press. It lists for $45.