This book on the presidencies of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe is superb. Even though it is chocked full of detail, the prose style of the author makes it read like a tale of high drama (which it often was).

Dr. Kevin Gutzman is professor of history at Western Connecticut State University in Danbury; he has previously written books on Jefferson and Madison. The trio of presidents examined here each served for two terms; the only other time that has happened is Clinton-Bush-Obama. Thus it seems appropriate to study this extraordinary 24-year span of early American history as a coherent whole. The first formal gathering of the trio happened at the University of Virginia on May 5, 1817, during Monroe’s presidency, although they had known each other for decades.

JEFFERSON

The era dealt with in this book began March 4, 1801, when Jefferson began his presidency. Elevating him to the “august status” of the “draftsman of the Declaration of Independence” was his close political ally James Madison. That Madison himself was no figure to be trifled with in this regard is also made clear by Gutzman. In his first elective office Madison “participated in drafting the first American declaration of rights and constitution, the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776. His tenure in the Continental/Confederation Congress (1780-83) played a key role in shaping Madison’s mature constitutional vision.”

In these days when the separation of church and state is under attack (such as the ludicrous governor of a certain state wanting to post the 10 Commandments in school) Jefferson took many opportunities over the years to “remind the public of his views concerning the proper relationship between government and religion, church and state.” Jefferson never issues a call for a day of prayer, which Presidents Washington and Adams had done.

The situation in Connecticut prompted the Danbury Baptist Association to write Jefferson in October 1801 about the “state’s omission to accommodate religious dissent.” He responded by invoking that “act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature it should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or promoting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.” Gutzman tells us something quite surprising about all this.

“While Jefferson’s most famous public pronouncement about government and religion has been central to discussion of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause since the 1940s, it apparently went unremarked in Jefferson’s day…Even the Danbury Baptist Association’s minutes let it pass without notice.”

Last year I visited the homes of Jefferson (Monticello) and Madison (Montpelier; shown in the lead photo). While the subject of slavery was hardly mentioned years ago, it is now a prominent feature of a tour. This book confronts the issue quite directly. “Madison owned more than a hundred. Jefferson owned more than 200. Hard though it is for us to believe now, they were born into a world in which essentially no one had ever said slavery was wrong.” Jefferson, as vicepresident, had to confront a slave revolt in 1800, when Gabriel Prosser organized slave men in Virginia to “rise against their masters.” Monroe was governor of Virginia at the time. He executed 10 of the slaves, but asked Jefferson for advice on how to proceed. “Where to arrest the hand of the Executioner,” he wrote to Jefferson, “was a question of great importance.” Jefferson counselled wisely, writing to Monroe “the world at large will for ever condemn us if we indulge a principle of revenge.” In response, Monroe admitted slavery was “an existing evil,” and conceded the Virginians living then bore some responsibility for its existence in that state. When Madison became president, his powerhouse of a wife, Dolly, “moved slavery out into the open to call it to guests’ attention.” She even “encouraged the pregnant Sally Hemmings to name her child James Madison.” It was known even at the time that Jefferson was the father, with Sally a mere black slave girl.

While Jefferson could take the high road, he could also take the low road. He caused a diplomatic furor by being disrespectful to Anthony Merry, the newly-installed ambassador from the United Kingdom. “In the light of the famous episode in which King George III had been notably rude on meeting then-Minister Jefferson for the sole time, it seems entirely possible that the president intentionally reciprocated the slight.” Yes, Jefferson could be petty. When they met, Merry was dressed in formal diplomatic garb; Jefferson walked in to meet him wearing what we might now call his pyjamas. “Not merely in undress,” Merry reported, “but actually standing in slippers down at the heels, with underclothes indicative of utter slovenliness.” He also refused to take the hand of Merry’s wife when going into dinner, a studied insult of the highest order in that age of decorum.

But in the country, he was quite popular. One notable figure from Maryland wrote “the President’s popularity is unbounded…his Will is that of the Nation.” That was in 1807, but in Washington, the tide had already turned in 1805. The author spends two chapters on the complex issue of the impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase. The Senate acquitted him, leading Jefferson to state what we all know now after the two failed impeachments of America’s great traitor: “Impeachment is a farce.”

Gutzman writes “No one knew it at the time, but the Senate vote was the high-water mark of the Jefferson presidency.” As another historian Gutzman quoted from 1996, “It was here that the Jeffersonian republicans fought their last aggressive battle, and, wavering under the shock of defeat, broke into factions.” The nail in the coffin was his Embargo Act on December 1807, which barred all foreign trade; it hurt Americans abundantly, the British barely, Napoleon not at all. It led one of his own constituents to call Jefferson “a damned rascal.” Gutzman explains that was quite an insult at the time. “This attitude toward the president grew increasingly common.” Towards the end of his presidency, “Jefferson essentially stepped aside.”

MONROE AND MADISON

The new Administration got off to a shaky start. At his inauguration, “Mr. Madison was extremely pale and trembled excessively.” John C. Calhoun was just starting his political career then, but he had pointed opinions. His view of Madison is illuminating. Madison “has not I fear the commanding talents, which are necessary to command those about him. He permits division in his cabinet. He reluctantly gives up the system of peace.” He had the misfortune to be president during the War of 1812. “Madison was out of his depth when it came to military matters… He had no clear conception of the proper distinction between the functions of civilian officials and those of military officers.” The press was caustic; the Boston Spectator referred to it as Madison’s “Wicked, Causeless War.” The result of Madison’s lack of leadership was a disaster for the young nation: the British burned Washington DC, including the Capitol and White House.

By contrast, Gutzman entitles his section on Monroe’s presidency as “The era of good feelings.” The great British parliamentarian Charles Bagot expressed the feeling of the new Administration. Monroe, he wrote, was “labouring to put the whole system of Government upon a different, and higher footing than that upon which it has long been placed, and to restore to it that strength and dignity of which it was so entirely divested by the doctrines and examples of Mr. Jefferson, and his Successor [Madison].”

Monroe was very prescient in his opinion about the danger facing the United States from the intractable issue of slavery. The so-called Missouri Crisis arose in 1820, 41 years before Civil War broke out. In 1820 Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state, but Maine was admitted at the same time as a non-slave state. In a letter to Jefferson, Monroe wrote “I have never known a question so menacing to the tranquility and even the continuance of our Union.”

The stage was set for a new president, John Quincy Adams. He delivered his inaugural message in 1825, which quickly made its way to Jefferson’s home. “Monticello,” Gutzman writes, “is about a hundred miles away from Washington DC, and its master finished reading Adams’s message highly upset.” By now an old man of 82, Jefferson would have suggested to the Virginia legislature that it pass a warning to the Federal Government that it risked resistance for exercising power not granted it through the Constitution.

He issued words of the greatest foreboding. Virginians, his resolution stated, did not want to break up the United States, as “they would indeed consider such a rupture as among the greatest calamities which could befall them; but not the greatest. There is one greater, submission to a government of unlimited powers.” For students of history, this broadside from the old war horse holds amazing resonance in light of the subsequent 203 years of the American experiment in democracy. A year after Jefferson drafted the resolution, he died. The Jeffersonian era ended.

There are two errors in the text. On page 179 it is stated Lord Harrowby is the “new British prime minister.” He was actually just the Foreign Secretary. Just two pages later, we are informed that Lord Hawkesbury is the British PM. He never was in that top job. On pg. 95, “United States issued” should read “issues”, and there are a couple of other minor typos. The book has no illustrations.

An incisive work, heavily reliant (as it should be) on the exact words printed, and written in private letters of the time, reading this is the finest way for anyone to understand the early 19th-century foundations of the presidency.

The Jeffersonians: The Visionary Presidencies of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. It lists for $37. Published by St. Martin’s Press.

Lead Image: Montpelier, Madison’s house. Photo by C Cunningham

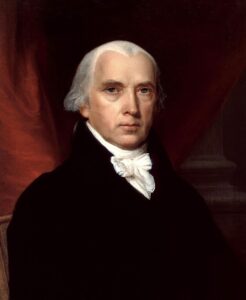

Image: Portrait of Pres. Madison is in The White House collection.

Addendum: On the day this review was written in 2013, President Madison was mentioned on national TV. It came in an interview on Morning Joe. Here is what presidential historian Michael Beschloss said:

“The founders, when they were designing our political system, were trying to do something that was the mirror image of the autocracies of Europe. This was not going to be about power; it was not going to be about celebrating one man; this was going to be a system of laws extremely carefully designed – largely by James Madison.”