The most recent issue of Transversal, the International Journal for the Historiography of Science, is devoted to the Belle Époque.

The phrase has entered the English lexicon, but identifying what it is may not come to mind so easily, especially when one struggles to find the E with a diacritical mark to spell it properly.

According to the Transversal editors, referencing the recent work of Dominique Kalifa, Belle Époque is actually a chrononyme. It “refers to the narrative construction of history around a specific period, marked by distinctive characteristics that warrant its identification with a proper name.” The author of this book, while fully conversant with all the relevant literature, decided not to burden the reader with the chrononyme designation. I have no compunction about burdening my readers with it though!

Mike Rapport (professor of history at the Univ. of Glasgow) has done a superb job at bringing to life the era from the 1870s to 1914. It is naturally focused on Paris, which in his book title is both the city of light, and city of shadows. As in all great chrononymes, such as Regency England in the early 19th century, there is a dark underside to society. Only the toffs get to experience the thrill of a grand ball in fancy dress, or the uplifting sights of the opera, and the luxury of now-iconic hotels. There has always been a dreary underclass, and anyone who wants to revel in misery can indulge in several chapters that even examine anarchists who “agreed that the abolition of the state, and along with it the privileges of the rich and powerful, would allow people to flourish.” So pathetic.

In this review I will concentrate on uplifting aspects of the Belle Époque. To quote Rapport, “It is an era remembered for its parade of wealth and style, the vibrant cafes with their witty conversation bubbling across the round tables that populated the pavements outside. Belle Époque conveys a frisson of erotic promise, of discreet affairs between errant men and women. The Belle Époque also recalls an age of speed and new technologies ushering in the twentieth century.” Among these were the first motor cars, the first Métro train, and the first aeroplane flights.

The major failure of the book is its lack of engagement with science in the Belle Époque. While the author does mention technologies, they are given short shrift: the development of pneumatic tires by Edouard Michelin, for example, is ignored, although the opening of the first cinema is discussed. In science, Pasteur developed the method named after him, pasteurization; Becquerel discovered radioactivity; and Marie Curie isolated radium and polonium. None of this is included in the book. Maybe a little less on crime and a little more on discoveries that have changed life in a good way for the whole world would be in order. He does thankfully delve into the work of Auguste Comte, whose “emphasis on science, knowledge, and education gave republicans a philosophy to support their scientific, secular world-view.”

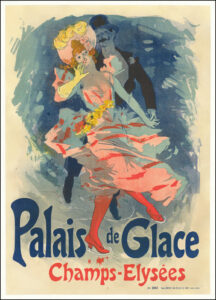

The book can be just as infuriating as the lack of proper medical care in the 1890s. On page 39 the author dilates on a beautiful pair of 1878 paintings by Claude Monet that depict the national festivities of 30 June commemorating ‘peace and work.’ Look closely at the painting of rue Saint-Denis, he instructs us, to see a flag emblazoned with Vive la Republique. This is infuriating as there is no illustration of the painting in the book! Indeed, the only graphics in the book are some sketchy B&W maps of small areas of Paris. An unfortunate editorial decision, which slants the book more towards an academic text rather than the popular text it aims to be. It is sad that the great poster art of the era, by such celebrated figures as Jules Chéret, is also unexplored in the book. I give an example here of his work from 1900, which is so evocative of the erotic promise of the Belle Époque.

Visually, the thing that most tourists gravitate to that still survive from the Belle Époque are the entrances to the Métro stations. Rapport tells us 87 still survive across 66 stations, about half of the original number. They “have come to symbolize the city itself,” he writes.

Those Métro trains symbolized speed, which Rapport identifies as one of the things people at the time struggled with. In 1891, a French doctor, Fernand Levillain argued that “the nervous condition was the natural result of urban living. The relentless pace of life in the metropolis punished the mental health.” Curiously, it was this very “Degeneration and hysteria that were blamed on these developments that would give the Belle Époque its nostalgic allure to later generations.”

Everything seemed to be changing, and what we now regard as great was often derided then as awful. For example, there was an exhibit of paintings by “Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Degas and Berthe Morisot in 1900. When the French president was being shown around, a member of the French Institute grabbed him by the arm and exclaimed, ‘Stop, it’s the dishonour of France.’” Today, those artworks are the honour of France, with Impressionist paintings among the most highly valued of anything ever done. Rapport also explores the denizens of a certain area of Paris in those days, where Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso, Renoir, and many others lived.

Rapport spends much time on the Dreyfus affair that rocked French society to its core. I found a fallout from that to be the most interesting point of all. “When, in 1899, Méliès started making a film about the Dreyfus Affair, based on the press accounts that he read, the film was banned on grounds that it would provoke public disorder.” Surely the first film ever banned by government authorities! Méliès is best known now for his 1902 film Voyage to the Moon. He would have been astounded to know that just 67 years later people really would walk on the Moon.

Rapport ranges widely, from the development of department stores and the related rise of female employment in them, to the rise of the bicycle that enabled them to reach the workplace. He pinpoints several statues that still stand to commemorate people and events that the people of Paris thought worthy. The largest of these is the bronze statue that “towers over the place de la République, erected in 1883 (lead photo). The unveiling of the statue was supposed to mark a moment of national reconciliation around the core democratic values of the Republic.” But like so much of French history, factional disputes and changing times caused trouble. It was only in 1880 that Bastille Day was declared a national holiday. Rapport explains this and much else with an engaging prose that gives us a very fine sense of the issues that created the chrononyme we think of as the Belle Époque.

City of Light, City of Shadows: Paris in the Belle Epoque is by Basic Books. It lists for $35.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Those who want to learn more about science in the era under discussion should read the papers in Transversal:

Reference

To the Belle Epoque. Transversal, vol. 17, 2024.

https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/transversal