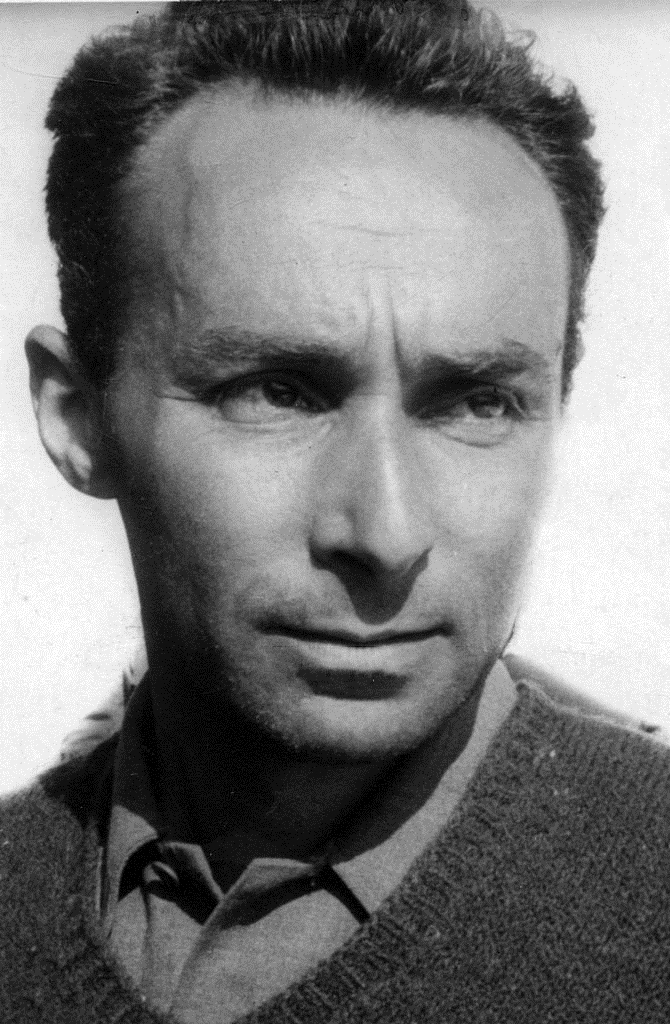

Photo: Primo Levi

In January 2025, the PM of Italy, Giorgia Meloni, announced a revamping the school curriculum by introducing Latin studies. The education minister, Giuseppe Valditara, also wants to introduce the study of music and art history from an early age, encourage the learning of poems by heart, and put a greater focus on the history of Italy rather than the rest of the world.

The Tuscan language that Dante wrote in has been a big factor in the creation of modern Italy. The author of Italy’s first modern novel, Alessandro Manzoni, translated his novel in 1840 into Tuscan. “Upon the unification of Italy in 1861, King Vittorio Emanuele II assigned him the presidency of a commission for the unification of the Italian language. Dante’s efforts on behalf of the vernacular helped create the language of the newborn Italian nation.”

Overall, I think Dante would approve of Meloni’s appeal to Latin. Even though he wrote the Commedia in the Tuscan dialect of Italian rather than Latin, I’m sure Dante would bemoan the fact that few Italians now have a working knowledge of Latin. And as for learning poetry by heart, the greatest Italian poet would certainly welcome that change!

The author of this book on Dante’s Commedia is Joseph Luzzi (professor of literature at Bard College in New York). He emphasizes throughout the book the importance of memorizing passages of the poem by heart. The famed architect Brunelleschi (1377-1446) “memorized patches of the Commedia, sprinkling references to it his notebooks and conversations.” Centuries later, the Italian writer Primo Levi (1919-1987; lead photo) found the “Commedia became essential to survival.”

Today, Jan. 27, 2025, the world is commemorating the 80th anniversary of Auschwitz, the prison camp where a million people were exterminated by the Nazis. Levi was a prisoner there. He met a Frenchman in the camp, Jean Samuel, who had the nickname Pikolo, Italian slang for messenger boy. One day they walked together to the cafeteria to retrieve the meager rations for their fellow prisoners. They “discovered their common love of books and study. Levi inexplicably recalled a line of poetry that he had long memorized, the famous words of Dante’s Ulysses in Inferno 26.118-120

Consider well the seed that gave you birth

you were not made to live your lives as brutes,

but to be followers of worth and knowledge.

“Such was the force of Ulysses’ speech that Levi felt as though we were ‘hearing it for the first time.’ It was he said, ‘like the voice of God. For a moment I forget who I am and where I am.’

“Recalling Dante, writes Luzzi, “Levi had a flash of disassociation, taking brief flight from his living hell.”

This is but one of many extraordinary insights Luzzi offers us here, in what he has pitched as a ‘biography’ of the Divine Comedy. (It was not known as Divine until a publisher added that word in 1555, more than two centuries after Dante wrote it.) Like the Divine Comedy, this short book (175 pages of text) consists of 10 chapters, and it serves as an ideal introduction to Dante’s great poem. For those who have never read it, peruse this book first! As for the best translation into English, that was done by none other than America’s greatest poet, Longfellow. Scholars gathered in Longfellow’s home to hear his translations, which led to the formation of The Dante Society of America.

So what exactly is the Divine Comedy? Luzzi quotes a line from Erich Auerbach’s 1929 book on the poem. “The content of the Comedy is a vision; but what is beheld in the vision is the truth as concrete reality, and hence it is both real and rational.” That is likely why Texas (yes, Texas), has banned the reading of the Divine Comedy in state prisons!!! Pope Paul VI described Dante’s poetry as “a dazzling star to which one turns to look and to ask the way to the good road.” The path to the good road is barricaded here. Pope Francis has called Dante “the prophet of a new humanity that thirsts for peace and happiness.”

Luzzi sets out here to “capture the essence of Dante’s meaning.” In this, he succeeds admirably. From an exploration of his seminal impact on Romantic poets and their “obsession with Dante’s persona” to a decisive move away from that into the “Modernist investment in his experimental poetics” championed by T.S. Eliot, Luzzi offers the non-specialist an easy (but not dumbed-down) way to explore Dante’s influence and reception through the centuries. With a rhetorical sophistication born of Dante’s own work, Luzzi has given us another treasure to cherish.

Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Biography, is by Princeton Univ. Press. It lists for $24.95

Image: Primo Levi, as he was in the 1950s. Wikimedia Commons.

Those most interested might want to consider joining the Dante Society: