Since everything Socrates said, or is purported to have said, is contained in the works of Plato, distinguishing between the two has always been problematic. Thus, if you going to buy one of the Handbooks the publisher Bloomsbury has recently issued, you really need to buy both! They are complementary in many ways.

The Handbook of Plato is weightier at 521 pages, compared to Socrates at 409. Both are also 2nd editions, the first having been published in 2022. The changes are notable. In the Plato book, topics not covered in the first edition include gender, time, animals, eschatology, Orphism and religious mysteries. Expanded areas of research since the first edition also see “new articles on comedy and metatheatre, emotions and Xenophon.” The Socrates book includes two new chapters on authors other than Plato: “one centred on Socrates as he appears in Aristophanes and another on Socratic thought as portrayed by Xenophon.” One author in the new edition (who is also one of the editors) goes into battle with a chapter by R. Waterfield in the first edition. Nicholas Smith decries the attitude of Waterfield, who wrote that we cannot understand the real Socrates unless we ignore every main source about him! “Waterfield’s dismissal of all our main sources leaves much to be desired,” he laments. I have added further details on the authorship of the Socrates book at the end of my article.

While both books are a comprehensive guide, their structure is quite different. The Socrates follows the typical academic format of a series of chapters, written by 16 scholars (including the editors). Each chapter is typically 20 pages. The Plato, by contrast, consists of more than 160 capsule essays, 2-4 pages each. The list of contributors runs to 8 pages! Thus, this is an encyclopedia-style book, which encourages readers to ‘dip in’ to the topics of particular interest. I’ll start with the Socrates book.

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Socrates

The tone of this entire book is actually set in Chapter 8, with a quote from the late scholar Gregory Vlastos. “If you believe what Socrates does, you hold the secret of happiness in your own hands.”

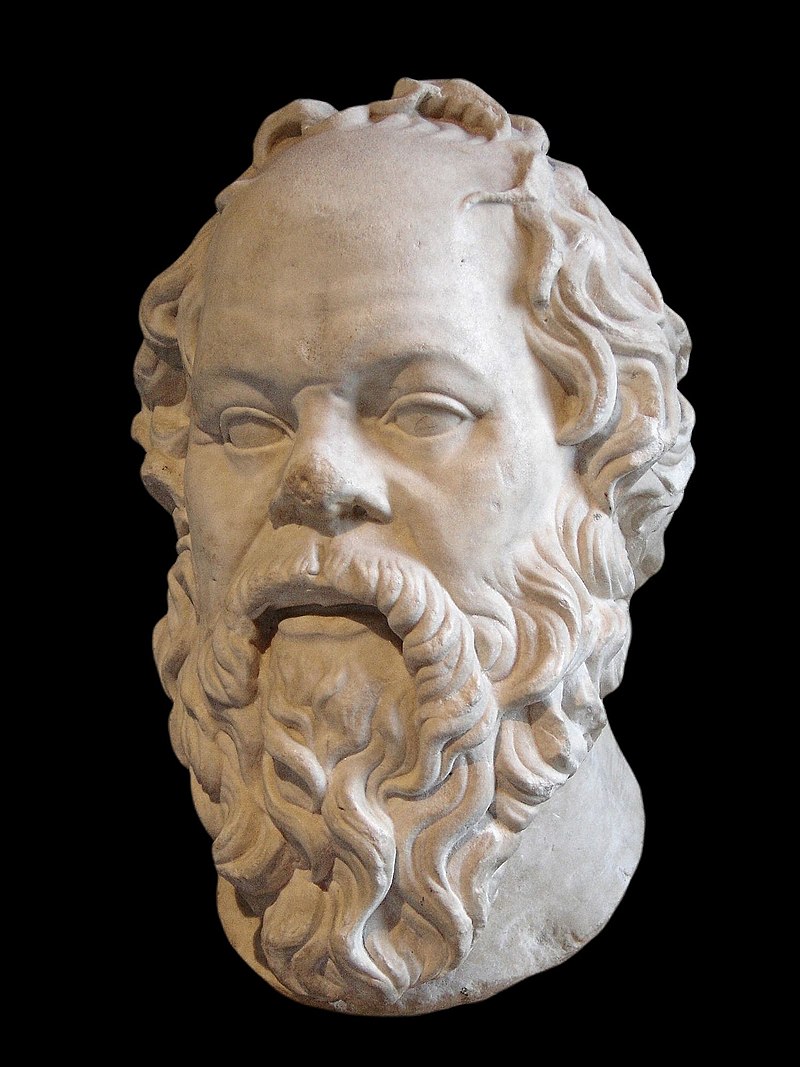

The first chapter is the new one on how Socrates is portrayed by Aristophanes in his play Clouds that was first staged in 423 BCE. Of his 11 extant comedies, Clouds is the only one devoted entirely to Socratic education, and “the only comedy which Plato explicitly refers in his dialogues.” Aside from the academic study of the play, what might engage the reader most is the very image of Socrates. On stage he was made to look like Silenus, a woodland deity who was half human, with the ears and tail of a horse. “It may well be that the Silenic Socrates portrayed decades later by Plato and Xenophon drew on a comic avatar, reinterpreting it as a philosophical icon.” It is this Silenic image of Socrates that persists to this day. (Neither book has any illustrations, so one must go elsewhere for the imagery.)

Dr. Stavru demolishes the widely-held view that Socratic thought is portrayed inconsistently in Clouds. “The wide variety of topics Socrates teaches, his religious beliefs and his ascetic lifestyle are not heterogeneous parts of an inextricable jumble: On the contrary, they form a unity which the plot of Clouds gradually unfolds.” The names of five prominent scholars who promoted the ‘jumble’ interpretation are coyly hidden away in a footnote. For the record, they are Grote, Starkie, Pucci, Dover and Gelzer.

For those getting started on Socratic scholarship, this new book highlights the importance of reading the latest studies; simply relying on big names from the past is just as likely to lead one astray as offering a source of enlightenment. This warning crops up again in the second new chapter, on Xenophon’s Socrates. Loeb editions are often considered to offer the definitive translation, but that is not the case. The authors of this chapter render a critical passage from Xenophon’s Memorabilia, dealing with circumstances which lead to regression in virtue, as

“And whenever someone forgets words of advice, he also has forgotten the state the soul was in when it desired moderation.” The Loeb version is “And whenever someone forgets words of advice, he forgets the experiences that prompted the soul to desire self-control.” In the new reading, “the point is that there is a tight connection between understanding the reasons for moderation and desiring to be moderate.” (Both this and another mis-translation issues are explored further in footnotes 34 and 35.) In a close reading of these ancient texts, such seemingly fine points often change our understanding in meaningful ways, so this Socrates book is a notable advance.

In another chapter, the author takes exception to the scholarship of Hugh Benson, whose references take up nearly half a page in the Bibliography. Under discussion is this chapter are Socratic methods. The author writes that a “serious problem for Benson’s interpretation is that it severs Socrates’ refutations from the pursuit of truth.” This goes to the heart of what Socrates is best known for. In the works of Plato, we see Socrates first targeting an interlocutor’s claim for testing or refutation. Socrates then elicits further premises, and finally shows that they contradict the targeted claim. “If Socrates’ refutations do not pursue the truth,” asks the chapter author, “why does Socrates at least occasionally advertise them as truth-seeking?…We do not have to think that Socrates’ conversations are either adversarial refutations or cooperative inquiries. They can be both.” This dovetails nicely with the following chapter on Socrates’ famous (and likely disingenuous) claim that he really was ignorant, and was just trying to learn from others. The author rather hilariously writes that “Socrates has great confidence in a cognitive resource that he does not share with other people. He seems to have no doubt at all this his daimonion (inner voice) is right in all its pronouncements, and never worries that he might be hallucinating.”

Dr Benson, who is being challenged in the ‘Socratic methods’ chapter, is himself the author of a chapter. He quotes Xenophon as stating “Socrates’ own conversation was ever of human things,” such as “what is madness, what is courage, what is government?” Benson, adding an important nuance to a topic discussed in the Plato book, writes that “Plato never uses Aristotle’s favoured term for definition (horismos), and rarely uses Aristotle’s other technical terms (horos and horizein) in the sense of definition.”

The chapter on Socratic happiness, with which I began this section of my review, has an insight into how his thoughts from ancient times can be applied now. “Only recently have modern ethical thinkers and psychologists taken moral injury seriously, as a result of research on the experiences of combat veterans, who often report something like the disordered sour described by Socrates, a soul at war with itself.” But before we leave that chapter, one must look again at the idea of happiness. “We moderns generally understand happiness as personal and subjective. But Socrates and other ancient Greeks do not think of happiness in this way. Socrates’ claim that everyone wants to be happy does not in itself imply that everyone is driven by self-interest.” To show how far away we are from a modern idea of happiness, the chapter author states that justice, as the principal virtue aside from wisdom, is what Socrates connects with happiness. Keep that in mind when you get a 10-carat diamond under the Christmas tree!

A chapter on the role of emotions in Socratic moral psychology is important, as it has received scant scholarly attention. The author of this chapter explains that for Socrates, “The evaluation beliefs that are expressed in emotions, when appropriate, can be even more powerfully motivating than purely rational beliefs.” But the author also cautions that “Because of their non-rational origins, only when emotions are in accordance with our reason are they both worthy of acceptance and of guiding our actions.” That, I think, is a stance Mr. Spock from Star Trek would approve of. Even though the emotions are “especially dangerous as guides to behaviour,” she explains further that:

“The capacity of emotion to be rational is for Socrates the reason for accepting some instances of it. Emotions must be regarded with scepticism in the ways they would lead us. But when they lead us in the right way, they can add potency to the motivations that help us to follow the right path.”

The Socrates book ends with a chapter on his trial and death. The added value of this chapter is an emphasis on the trial from the pen of Xenophon, who does not serve “his own anti-democratic political views through his depiction of Socrates by defending some of Socrates’ allegedly anti-democratic political doctrines. Instead, Xenophon focuses on Socrates’ strength of character.” Those who only know of the final days of Socrates from the text by Plato will find this chapter quite illuminating in its critique of the credibility of sources.

There is a typo in the Socrates book: ‘service to the god’ should be ‘service to the good’ on pg 186; and on page 391, the reference to a book by van Ophuijsen is duplicated. The book is uniformly superb, but I wish one aspect had been delved into. In the chapter on Socrates on Death, the author looks at Plato’s Crito, where Socrates’ ability to sleep sound is marvelled at. “Socrates explains his easy slumber by recounting a pleasant dream,” but there is no exploration in any chapter of the role of dreams in the Socratic experience.

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Plato

This book is not a consensus but an array of viewpoints on every aspect of Plato scholarship, all of which can be explored further in a Bibliography comprising an amazing 82 pages. This second edition features 19 newly commissioned entries.

The Introduction by the authors state “We are in a period of significant change in the orientation and content of thinking about Plato. The trend is towards more holistic, contextual and interdisciplinary approaches.” Thus, we get this “new kind of guide,” which I have described as encyclopedic; the editors do not use this descriptor. Since such a text cannot be ‘reviewed’ in the traditional sense, I will just give here a few highlights that struck me, primarily as it relates to the Handbook of Socrates.

There is a section on the influence of Pythagoras on Plato, although “recent overviews suggest that Plato is explicable with little mention of Pythagoreanism.” In this entry, Carl Huffman states that “Pythagorean influence appears in Plato’s career in two areas, the fate of the soul and mathematics.” In this he unfortunately does not reference a book by University of Texas (Austin) professor Alberto A. Martinez, which examines this issue (The Cult of Pythagoras, 2012). An entry by Christine Thomas makes the point that, for Plato, “the ultimate aim of mathematical education is successful apprehension of a particular form, the form of the good. The form of goodness itself plays the role of the first principle of everything.”

Speaking of the soul, an entry on Plato’s life by Menahem Luz mentions a text entitled Miltiades, by Aeschines of Sphettus (435-355 BCE). In that text, “Socrates persuades Miltiades to complete an education of the soul in addition to that of the body.” Valuable to know, as this text is not mentioned in the Handbook of Socrates.

Also not mentioned there is a Socratic dialogue supposedly by Plato called the Clitophon. In the text, Clitophon “complains that Socrates never takes the step of teaching is what virtue is…Clitophon therefore claims that Socrates either does not know what he is taking about or is keeping his knowledge from others.”

“Even if the Clitophon were neither by Plato nor Platonic,” writes Francisco Gonzalez, “it would still be a valuable record of an ancient critique of Plato’s Socrates.”

Entries in the Handbook of Plato are divided in to 5 sections: 1. Plato’s Life: Historical, Literary and Philosophic Context; 2. The Dialogues; 3. Important Features of the Dialogues; 4. Concepts, Themes and Topics treated in the Dialogues; 5. Later Reception, Interpretation and Influence of Plato and the Dialogues.

Taken together, these two handbooks are an ideal snapshot of Platonic and Socratic scholarship in 2024. The “significant change” currently underway, at least in Platonic studies, certainly presages that further revised editions will be needed in the future. Every Classics library, whether personal or institutional, should have these two edited books.

Unfortunately, a book about Plato’s Euthyphro and its study by the scholar Leo Strauss was published too late to be included in the discussion in either book; particularly the entry here by Catherine Zuckert on Straussian Readings of Plato. I reviewed it in January this year:

I would also refer the reader to a 2024 book published by Brepols, which explores the fascinating understanding of Plato in Medieval England, edited by Christopher Moore.

AUTHOR DETAILS FOR SOCRATES BOOK

In the second edition of the Socrates book, some authors are retained from the first edition. These are William J. Prior (he previously wrote on Metaphysics, but in this edition about the Forms); Keith McPartland (Socratic Ignorance), Hugh Benson (The Priority of Definition), Nicholas D. Smith (co-author of a chapter on Moral Psychology in the first ed., but here he writes on The Trial of Socrates); Suzanne Obdrzalek (Socrates on Love), Curtis N. Johnson (Socrates’ Political Philosophy), Mark McPherran (Socratic Theology and Piety). New to this edition are Emily A. Austin (Socrates on Death and the Afterlife), Eric Brown (Socratic Methods), Justin C. Clark (Socratic Virtue Intellectualism), Irina Deretic (Socrates on Emotions), Russell E. Jones & Ravi Sharma (Zenophon’s Socrates), Freya Moebus (Socratic Motivational Intellectualism), Alessandro Stavru (Socrates in Old Comedy), and Paul Woodruff (Socratic Eudaimonism). This book ends with 27 pages of Bibliography.

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Socrates lists for $122. It is edited by Russell E. Jones (assistant professor of philosophy at Univ. of Oklahoma), Ravi Sharma (assistant professor of philosophy at Clark Univ.) and Nicholas D. Smith (professor of humanities at Lewis and Clark College).

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Plato lists for $133. It is edited by Gerald A. Press (professor of philosophy at Hunter College, who died in 2022) and Mateo Duque (assistant professor of philosophy at Binghamton Univ.)

Images: lead photo of Socrates is a Roman artwork (1st century). Likely a marble copy of a Greek statue. In the collection of The Louvre. Public domain.

Plato, as depicted by Raphael in his fresco The School of Athens.