“With the exception of the genesis of living beings, it is perhaps the greatest of terrestrial creation.”

What was Johann Gottfied Herder referring to? The power of speech.

“Everything human that men have ever thought, desired, done, and will yet do depends on a puff of expelled air: for all of us would still be roaming about the forests had this divine afflatus not inspired us and floated on our lips like an enchanting note.”

In such florid prose did Herder embellish much of his book, Ideas for the Philosophy of the History of Mankind. Its first full English translation has just been published, by Gregory Martin Moore (professor of history, Georgia State University). Having already published two books on Herder (1744-1803), Moore is in a prime position for tackling this very long (707 pages) and difficult book.

I think one reason it has taken from the late 18th century until now to be fully realized in English (from the original German) is that Herder falls back on a single explanation for everything he can’t explain. This is already evident in the quote I gave: the word ‘divine’ signals his unwavering belief in divine explanations. This, of course, runs counter to science, which since his time has entirely overthrown divine explanations. And indeed, in 18th century France the prevailing opinion of the Enlightenment was quite opposed to the divine, in favour of reason. So even when it was written, Herder was whistling in the dark. Once evolutionary principles were established in the 19th century, and made real in the DNA laboratory of the 20th century, no serious text still resorts to teleological explanations.

Herder is not overly enamoured with the Enlightenment, to put it kindly, as we learn in one of his wide-ranging chapters. “It is an idle boast when, in respect of what we call enlightenment, art and science, so many undistinguished Europeans claim superiority over the other three quarters of the globe and, like the madman who beheld the ships coming into the harbour, fancy all the inventions of Europe their own.”

Moore writes that “Herder offers a kind of providential history – a vindication of divine agency in human affairs – but refuses to draw any definite conclusions as to its goals or to resign himself to the whims of fortune.” And as he titled his book as merely “ideas” for a history of mankind, a potential reader might approach this as a work left unfinished. And indeed it is, as his text stops in the Middle Ages. Herder also states “The best essay on the history and diversity of the human heart and understanding would be a philosophical comparison of the languages: for every one of them is imprinted with the understanding and character of a people.” Alas, this study is one idea he merely proposed. This Ideas for a Philosophy book is not it.

Herder sincerely believed, writes Moore, that “modern science and primitive revelation express the same eternal truths.” Even Herder’s mentor, Johann Hamann, was unable to discern the ‘plan’ of the text. The beginning traces the origin of the universe itself, and then the rise of life on Earth, culminating in an essay whose premise is that human organization is a system of spiritual forces. In Part 2, he traces the relationship between climate and different peoples, ranging from those who live in the Arctic, the temperate areas such as Europe, and the equatorial regions. Part 3 is a survey of ancient civilisations, while Part 4 traces the rise of Europeans in various areas of the continent, and also Arabia. The books ends with some general remarks on the Crusades and the culture of reason in Europe.

Moore refers to Herder’s text as a jeremiad: a text where an author bitterly laments the state of society and its morals. Not very inviting to a 21st century reader! So, what is the silver lining of this book? “It represents,” states Moore, “a necessary first step toward clearing away the false assumptions of the present; it promises ‘to form mankind’ in the sense that it delivers a moral lesson, tells us what is and what is not possible; it instructs us as to the limits of our capacities.”

But even Moore yearns for what he terms “a more honest philosophy of history.” Instead of beginning with abstractions and grand theories, as Herder does, “it would seek to disentangle the ‘thousands of cooperating clauses,’ moral and physical, that shape the lives of human beings.”

Despite these misgivings, Herder created some prose that seems to fit quite well with the situation the U.S. finds itself in now. Man, he writes

“can give an air of plausibility to the most deceptive error and become a willing dupe; he can learn in time to love the chains that shackle him, against his nature, and adorn them with flowers. As with deluded reason, therefore, so also with abused or fettered freedom. When yoked to mean instincts and bound to vile habits, he is often capable of becoming worse than a brute.” The number of dupes in the U.S. can even be measured by the number of votes cast in favour of abused or fettered freedom: 77,168,458. “Under the yolk of despotism,” wrote Herder, “even the noblest nation soon relinquishes its dignity: the very marrow in its bones is crushed; and its most refined and precious gifts are misused for mendacity and deceit, fawning servility and extravagance.” As we look into the past to read Herder’s words, we look into our own bleak future.

The translator has done a great service here for any scholarship that deals with the sense of history and global sociology/anthropology as understood in the 18th century; especially as understood in the area that became the country of Germany in the 19th century. One can also here see here concepts that appealed to the Romantic writers in the early 19th century.

Moore offers a 65-page Introduction. This might seem rather extensive, but he points the reader to a German-language book that offers 1,000 pages of analysis of Herder’s text! The English-only reader can breathe a huge sigh of relief that this will forever be locked away. No chance of adding that to the beach holiday!

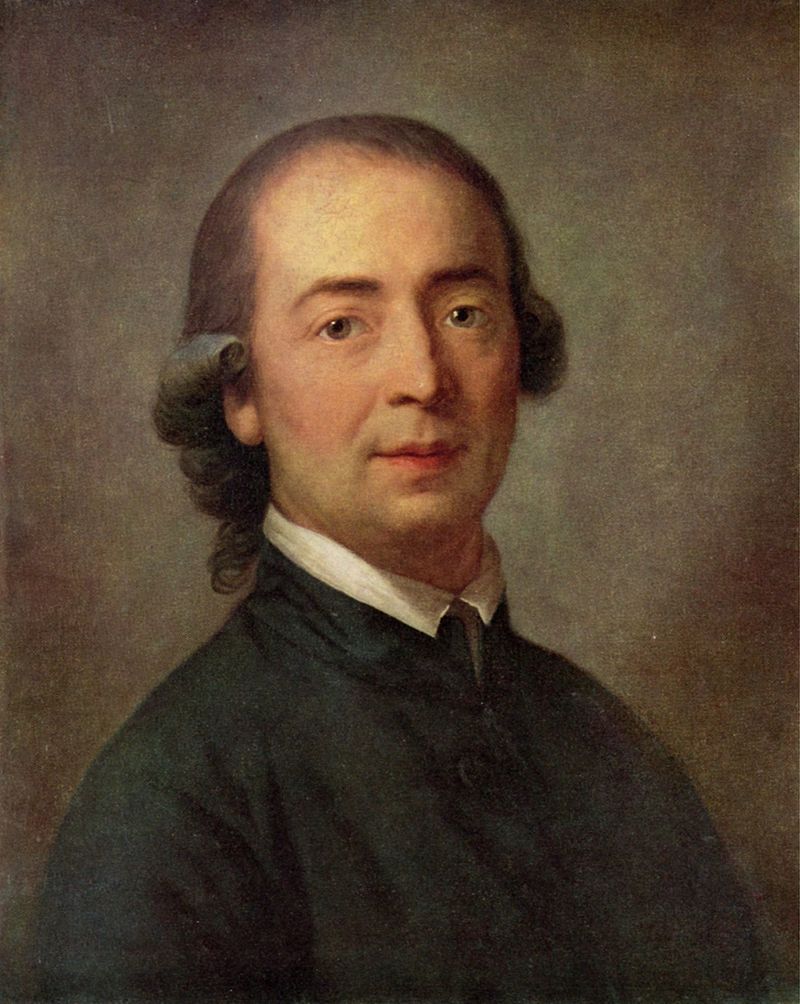

Image: a 1785 painting of Herder, now on display at Gleimhaus, the oldest literary museum in Germany. In the public domain.

Ideas for the Philosophy of the History of Mankind is by Princeton University Press. It lists for $80.