Suppose you, and many others, were of two minds on a critical issue. “Which suggests not only that opposing positions are held, but that the person holding them is aware of the contradiction and might even say it out loud. Which means that, to put it paradoxically, disavowal is an admission of denial. Which means, in another sense, it’s a denial of denial. Because after all, if I’m admitting I’m denying something, then how can I be denying it?”

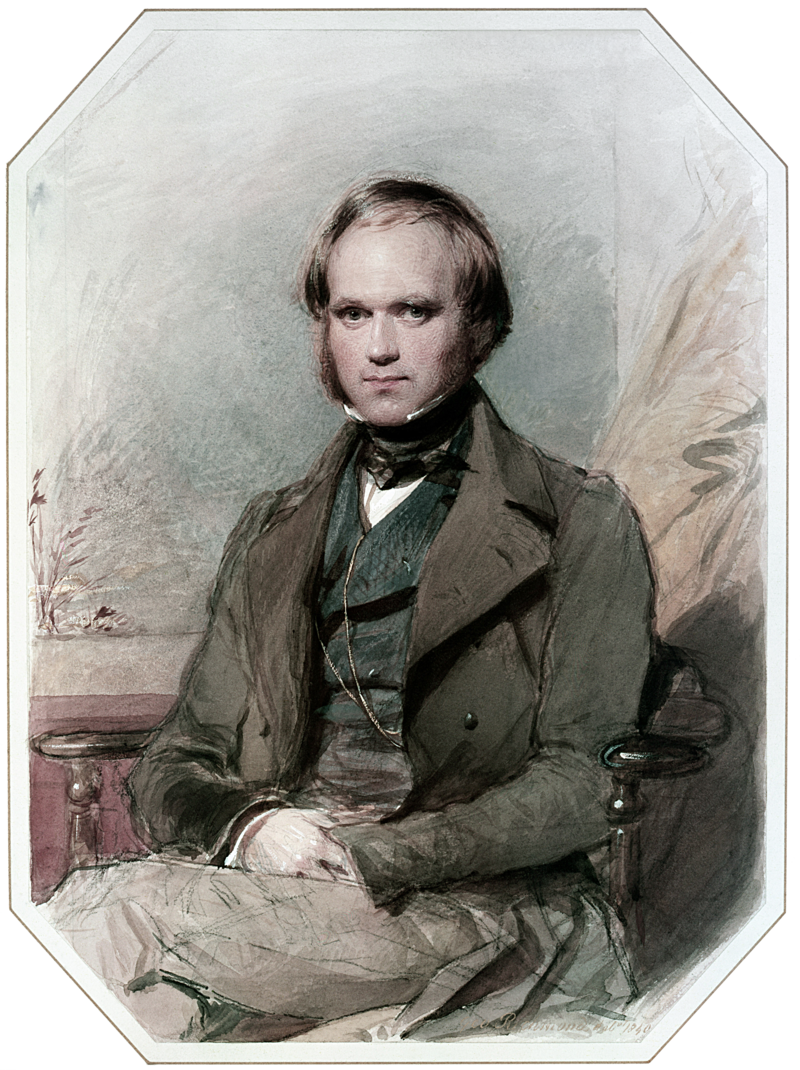

Here I quote from a book launch by University of Texas (Austin) English Professor Allen MacDuffie. The critical issues he refers to throughout his book is the engagement with the theory of evolution by Charles Darwin (pictured here), and the claims of climate change. He explores various shades of denial (including disavowal) through the lens of literature, mostly from the mid-19th century up to the 1920s. Exploring scientific concepts in this time period through its literature has proved fruitful for others scholars. For example, Henry Gee (not mentioned by MacDuffie) approaches literary models from Shelley to Kafka as a way to explicate the properties of Deep Time. This concept naturally arises in any discussion of Darwin, who needed to place the ancestry of homo sapiens in an unspecified deep time; modern technology has allowed us to put dates on our ancestry going back millions of years, but Darwin and his contemporaries were in the dark on this; and also the age of the Earth at some 4.6 billion years, whose date would have been rejected by most scientists in the 19th century as impossibly old.

Suppose once again you are a reader 99 years in the past, and you have in your hands a copy of Virginia Woolf’s new book, Mrs. Dalloway. “We learn,” writes MacDuffie, “that Clarissa Dalloway spent her childhood reading the works of Victorian scientific naturalists and that this experience has left her dwelling in a set of paradoxes.” Here follows a passage from Woolf’s book:

“As we are a doomed race, chained to a sinking ship (her favourite reading as a girl was Huxley and Tyndall), and they were fond of these nautical metaphors), as the whole thing is a bad joke, let us, at any rate, do our part; mitigate the sufferings of our fellow prisoners (Huxley again); decorate the dungeon with flowers and air cushions; be as decent as we possibly can.”

As we are approaching Halloween, I was especially delighted to read this interior decorating advice, as I wasn’t sure if flowers in the dungeon were appropriate!

MacDuffie began his address at the University of Texas last week by explaining the role of Darwin in his study. “I should begin by saying that this project started with something of a conundrum. On the one hand, Charles Darwin is maybe the most important figure in the history of ecological science. He is considered by me to be the “father of ecology” for the way he theorized the impossibly complex, mutually shaping relationship between and among organisms, habitats, and wider environmental conditions. Yet, Darwin was not really seen as much of a green thinker, green thinker in the 19th century, the period I studied: he barely factored in discussions of 19th century ecological imaginary. Instead the focus tends to be on figures like John Ruskin and Charles Dickens – writers who denounced the outrageous forms of waste and environmental degradation they saw, but who didn’t seem all that deeply influenced by Darwin, as I think is especially the case with Dickens. So that was the question that got this project started.”

MacDuffie posits that we are living in a culture of denial in that much of humanity fails to realise what Rachel Carson termed the “obvious corollary” of Darwinian thought: we are fully enmeshed in material environments like all other organisms. “This book is about that culture,” MacDuffie writes in his Introduction. One expression of this is how Darwin’s theory was co-opted by social and political movements in the 20th century. We are accustomed now to the so-called ‘weaponisation’ of (for example) the Justice Department in the United States. That, of course, is just a lie propagated by modern-day Nazis, but in the 1930s “Darwinian theory was weaponized in the extermination credo: life unworthy of life.” MacDuffie quotes Franz Fanon in his indictment of European hypocrisy: “They are never done talking of Man, yet murder men everywhere they find them.” MacDuffie identifies this “as a cognitive dissonance, the engine of denial, at the very core of Western liberalism.” A main thread in his argument as the book unfolds is to show “the denial and disavowal of Darwin was always interwoven with other forms of willful blindness and forgetting that actively obscured the violent, destructive underside of the ascendant liberal order.” Whether or not you agree with this attack on the liberal order, the book is worth reading.

There is a fine interlude in the book where we get to relax with Darwin at a hydrotherapy resort in 1858. He “spent his time getting lost in the latest novels by Anthony Trollope and George Elliott.” Trollope (my favourite Victorian author) is, says MacDuffie, “the high priest of metafictional necromancy, interrupting his own stories to point to, wink at, and even complain about their adherence to manifestly artificial conventions.” It was in such Victorian novels that “an ‘evolutionary’ conception of the human was made imaginable and that found its culminating expression in Darwin’s mature work.” For this, MacDuffie expresses his deep debt to a 2019 book by Ian Duncan, Human Forms.

The arguments in the book are rich and dense, fully deserving of a close reading. I’ll just quote a bit from his UT talk to give an idea of the interaction between Victorian literature, and Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

“Thomas Henry Huxley is a writer who, at first glance, seemed to have a response to evolutionary thought, radically different from what’s going on with Charlotte Brontë. Huxley did not turn away from the ideas that brought Brontë to the up edge of unutterable desolation. On the contrary, he earned his nickname “Darwin’s Bulldog” precisely for his eagerness to publicly confront those who trafficked in what he called “willful ignorance.” And yet, despite seemingly stark differences between the secular, liberal, agnostic, Huxley, and the Tory, Evangelical Brontë, both strikingly wind up in very similar places. Both come to believe that there is something about the radical import of these ideas that should not be fully known. And both put the veil back in place in different ways.

“So, this quote is from Man’s Place in Nature, where Huxley argues, ‘But there is no absolute structural line of demarcation between the animals and ourselves. Huxley is here openly embracing one of the most radical implications of Darwin’s theory, the complete continuity of human beings with other forms of biological life. The idea that our species, including our own conscious experience, is embodied material produced by and enmeshed in the natural world and the web of life.’ So far so good. But then, the very next breath, he changes gears: ‘At the same time no one is more strongly convinced than I am of the vastness of the gulf between civilized men and the brutes, or is more certain that whether from them or not, he is assuredly not of them.’

“It’s a bizarre moment because he seems to be saying two opposite things at once: There’s no line of demarcation between humans and other animals, and yet there is a vast gulf. What exactly is a gulf? A divide, an abyss? And how is that not a form of demarcation? The felt sense of discontinuity is conjured as much through the quiet shift in the ground of figuration towards a kind of strategic lyrical vagueness as it is through the figure itself.

“Also, I don’t understand the claim that humans are from animals but not of them. How can there be genealogy without ongoing relation? But that sound of precision mutes the contradictoryness of the position he wants to take. Because that position is humans are animals and humans are not animals.”

“So, I’m interested in denial, but not what we usually think of when we use the phrase ‘science denial.’ Not the kind of outright rejection peddled by either creationists and conservative members of the Victorian scientific establishment then, or the various cranks and con artists that continue to peddle false information about climate science today. That kind of reactionary denialism is important. It was, and it is certainly part of the reception of evolution. And it’s obviously a major factor in our own shamefully inadequate response to the climate crisis today.

“But my focus in this book is on something a little different, a quieter, more equivocal form of denialism that was absolutely widespread in Victorian culture, but one that often got overshadowed by the more brazen reactionary versions. I’m talking about a form of denial characterised not by rejection but by acceptance. A response that seems closer to what Freud called disavowal, or what Naomi Klein has recently called soft denial. Not falsification or refusal or repression of unwelcome facts, but a temporary pushing out of mind, a strategic forgetting, a way of knowing something is true and not knowing it at the same time.

“In the 19th century, such a contradictory structure of feeling was characteristic of a culture that was at once trying to come to terms with and trying to avoid the reality of its relationship to the natural world and thus its situation on this planet.”

Heady stuff indeed, so I highly recommend this title not only to the scientifically-minded but others whose main study is literature, or the sociology of denial. An important book!

Allen MacDuffie is Associate Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Victorian Literature, Energy, and the Ecological Imagination (2014).

Climate of Denial: Darwin, Climate Change, and the Literature of the Long Nineteenth Century is by Stanford Univ. Press. It lists for $130 (hardback) and $32 (softcover).

Reference

Gee, Henry (1999). In Search of Deep Time: Beyond the Fossil Record to a new History of Life. New York, Free Press. Editorial note: Another book that can be profitably read alongside this one is Deep Time: A Literary History, by Dr. Noah Heringman (2023). It also engages quite a bit with Darwin, and will be reviewed soon in Sun News Austin.