It was 373 years ago that Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan, a book that many regard as THE masterwork of political philosophy. It was in large part a response to the English Civil War that raged from 1642 to 1651, the terminal year in which Leviathan first bestrode the stage. Its frontispiece is the most famous example of such an artwork, and it alone has spawned innumerable explanations.

For those scholars who have studied Leviathan, the accolades reach the highest pitch. Just to give one example, I will offer a quote from the great historian Jonathan Sumption, who is now a judge on the Supreme Court of the United Kingdon: “The best reason for reading Hobbes is that no other philosopher has ever used the English language to such powerful effect.”

Before getting into the central theme of this new book by Dr. J. Matthew Hoye (Leiden University), I am printing a quote from the philosopher Dr. Arash Abizadeh (McGill University, and author of a book on Hobbes) that highlights exactly what is wrong with the prevailing scholarship on Leviathan.

If someone is interested in international politics, often they’ll just read chapter 13, which is where he gives you his theory of war. If they’re interested in his political philosophy often what people do is read Books I and II, and leave Books III and IV aside—that’s where he deals with religion at length. But if you’re interested in his religious, theological and ecclesiastical thought—which is not irrelevant for his political thought—then books III and IV are indispensable. Even if you want to skip Books III and IV, often people will read I and II plus the Review and Conclusion.

A fine recommendation for a first-time reader of Leviathan, except for the fact he says nothing about Chapter 12. According to Hoye, that is the key chapter in Leviathan, one which has consistently been passed over because it doesn’t seem to ‘fit.’ Well, it may not fit what modern scholars find acceptable, but Hoye has done the world of scholarship a tremendous service by placing Chapter 12 at the centre of any reading of Leviathan. This is just the sort of book I like: revising received wisdom! Hoye is quite clear that “my account of Hobbes does not radically upend the standard model,” but I think many readers will conclude after reading it that Hoye’s revelations are of a more profound character. As Hoye himself states, what he gives us is nothing less than “a new account of Hobbes’s political theory.” This book will likely be received in the hallowed halls of Leviathan scholarship like a magnitude 8 earthquake: more than just a few dishes will be broken.

Most scholars regard Leviathan “as a text intended to persuade or teach readers to obey.” Hoye finally places Leviathan in its proper light: it is meant to teach sovereigns how to rule, essentially the exact opposite of what the standard model is based on. “Hobbes’s many discussions of virtue and sovereignty,” Hoye writes, “are not tangential but elemental to his account of sovereignty.”

I found the motive force of the book to be best stated on page 63.

“What, if any, is Hobbes’s theory of new foundations in Leviathan? I believe Hobbes has a compelling answer: new foundations are wrought through constitutive rhetorical action carried out by eminently virtuous leaders. That claim may strike readers as doubly impossible: the scholarship on rhetoric in Hobbes does not support the claim, while the standard model of Hobbes’s political philosophy denies its very possibility.”

In the remaining pages (from 64-299), Hoye reclaims the work of Hobbes from one that has been overburdened with cannibalistic scholarship (very similar to what we find in Milton studies, another 17th century scholar who has been widely misinterpreted). In a supreme act of scholarly prestidigitation, Hoye lifts the curtain before the eyes of an astonished audience. It would be like David Copperfield making a goat disappear on stage, to be suddenly replaced with a Palomino horse. Readers of Leviathan can now ride the horse to further understanding of this great 17-century text.

So, how does he do it? Even to summarise the complex arguments of this book is beyond the remit of any book review, but I will trace a salient thread. Readers will have to attend very closely to gain the insights Hoye promulgates.

In a section on the Roman reconfigurations of rhetoric, Hoye focuses on actio, one of the five aspects of the rhetorical arts. For Cicero, actio was the “most important and powerful of the rhetorical techniques, and the most plebeian.” Meaning that it is the technique by which sovereigns can sway the populace to a certain point of view. “For Cicero, delivery, in conjunction with style, gives the orator access to the passions of the multitude,” Hoye writes. This argument is covered on Pages 88-93.

Moving forward to page 143-144, in a chapter on rhetorical action in Leviathan, we see that “when Hobbes is pushed to describe how a [sovereign] should act, the language that he turns to is that of rhetorical action.” Of the four abuses of speech Hobbes identified, his words on grieving are the key. He says using the tongue to grieve is an abuse of speech “unless it be one whom we are obliged to govern; and then it is not to grieve, but to correct and amend.”

Hoye’s analysis of this passage is crucial. “The point, though rarely remarked upon, strikes at the very nature of sovereignty. Hobbes is saying that rulers will not only have need to deploy ‘speech and action’ but that it may be the only modality for driving home such political corrections in exceptional political moments.” Hobbes was surely thinking about the Civil War in this context.

Hoye has nothing good to say about the virtue ethics interpretations of Leviathan, “which have not registered Chapter 12 or considered the virtues of sovereigns (or founders), focusing only on the virtues of the ruled.” By demolishing both the “implicit and explicit accounts of new foundations provided in the standard model,” Hoye gives an example of how Chapter 12 has been regarded by one of the few scholars who has written about it. “Charles Tarlton pays close attention to 12, only to argue that Hobbes does not actually mean what he said in 12.” In reality, as Hoye teaches us, “the lessons of 12 are what they attest to be.”

As he summarises on page 210, “The soul of Hobbes’s theory of new foundations is found in 12. In it he describes the essential and immutable role of the (would-be) sovereign’s character in founding and maintaining regimes.”

An important book not only for scholarship on Leviathan, but for the entire embrace of sovereign power in the 17th century and beyond. For those with a decent collection of books on Leviathan, this might be a good time to lighten the load on your bookshelves: take some of them to the used bookstore, and replace them with this one.

There are a few typos: Addition should be edition (p 117); Have be should be have been (p141); Contended should be contend (p 168); Example should be examples (p 184); but me should be but let me (p 187).

Author Bio

Matthew Hoye is Associate Professor of Global Justice at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University. A political theorist by training, Hoye has a background in the history of ideas and philosophy. He obtained his PhD from the New School for Social Research in 2013 and was a visiting fellow at the Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies in Toronto and at Queen Mary, University of London. More recently, he has worked at Maastricht University and Vrije University, Amsterdam.

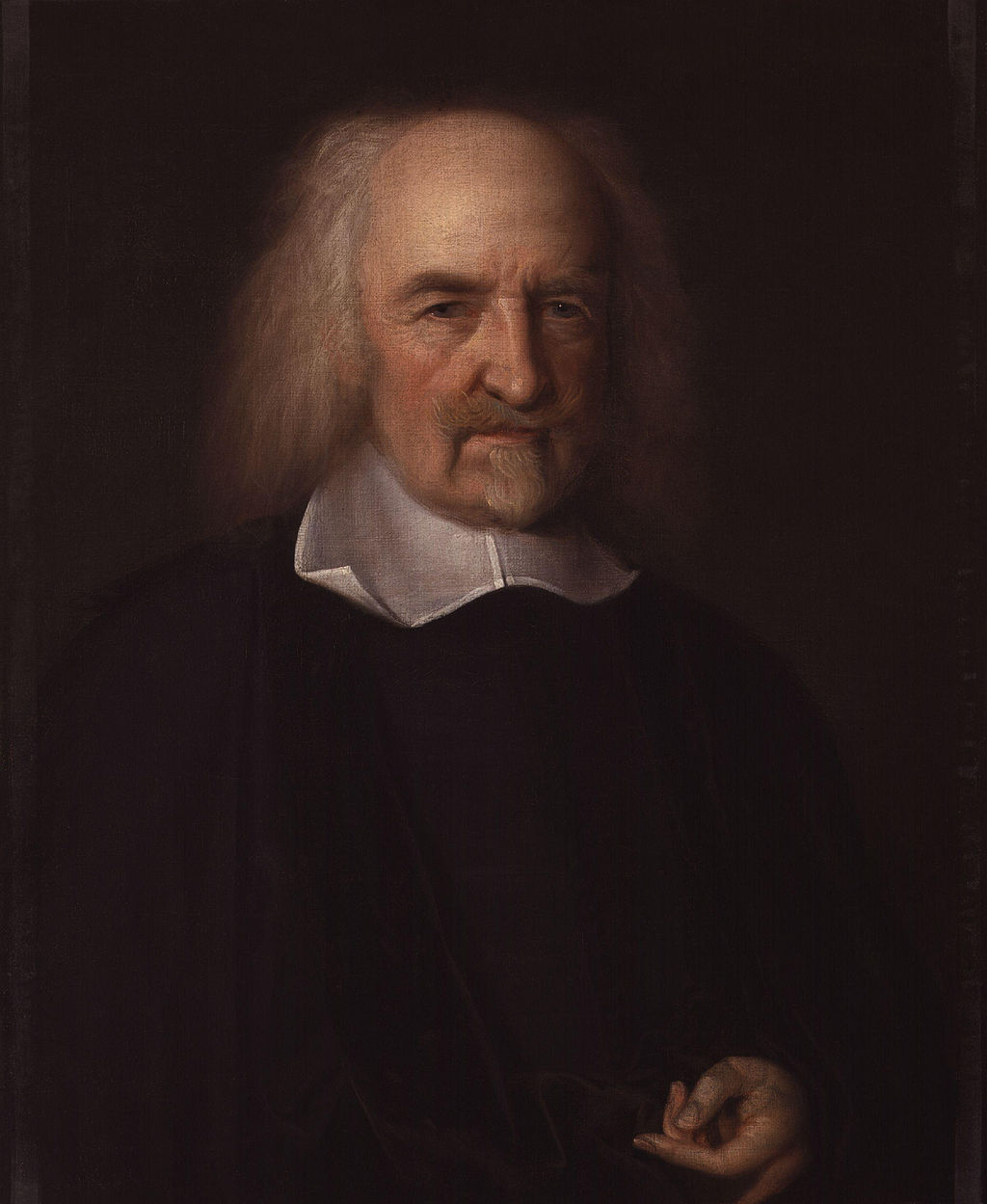

Sovereignty as a Vocation on Hobbes’s Leviathan is by Amsterdam University Press. It lists for $148. Image: A portrait of Hobbes done in 1670, in the National Portrait Gallery, London. In the public domain.