This book focuses on 18 lives, but it should have been 19. Author Adam Smyth (professor of English literature at Balliol College, Univ. of Oxford) omitted one of the most important of all 19th century bookbinders. This is all the more mystifying as the person in question was an expert in medieval manuscripts and ancient texts, the very subject matter Smyth uses as the bedrock of his bookish analysis.

Henry Noel Humphreys (1810-1879) is best known for a suite of chromolithographed books published by Longmans in the 1840s. The most extraordinary of these is the 1849 production A Record of the Black Prince. The colour illustrations were very rare back then, but even more extraordinary is the binding: a handmade ‘papier-mâché’ binding that is solid black, to reflect the subject of the book: The Black Prince (1330-1376) was the son of King Edward III. An expert has termed this “the most successful of all gift books of this period – the binding is the most elaborate yet of all black Papier-mâché kind.” While printed in the 19th century, it most resembles a production of the 16th century. Smyth would not have had to go far to consult an expert on this. Julie Blyth, assistant librarian at Corpus Christi College (also at Oxford University) wrote about the process: “Known as papier-mâché, or carton pierre bindings, the boards were machine-made using a plaster and antinomy mixture combined with or applied over papier-mâché, then pressed over metal frames or into moulds. The patent for this process was held by the firm J. Jackson & Son, who also produced architectural mouldings for furniture, picture frames, carriages, etc. The technique is especially associated with the British graphic artist, writer and antiquarian Henry Noel Humphreys.” All in all, this would have been a perfect fit for the book under review.

So much for what is NOT in Smyth’s book! In book about books, it seems appropriate that a felloe name de Worde was the to print a book in England with Arabic characters. That was in 1528. The book also contained another first. “Typographically, this was a remarkable effort by de Worde: the first use of italic in England.” The use of Arabic was a real stunner, and it was not until 1592 that another English book-maker used Arabic type. Books were printed in the 16th century that required type in “Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopian,” so what was their solution to this problem? After the book was printed, the foreign scripts were printed by hand into each copy of the book!

For each of the book-makers Smyth studies here, he does far more than merely describe what they did in the book trade. He brings each one to life. For de Worde, as an example, Smyth looks at his will, dated 5 June 1534, six months before his death. His bequests were a bit peculiar: to his maid he left three pounds of books. Not books worth three pounds in money, but books that weighed a total of three pounds! Smyth speculates on this, perhaps a bit tongue in cheek. “Maybe Alice was a reader: a servant who paused to look over the piles of inky sheets stacked beside the press before they were sent to the binder to fold, sew and cover. His other servants got books too.” Knowing the literacy rate then, I find it highly unlikely any servant could read. This also reflects the value of books in the early days of printing: de Worde himself published more than 15% of the entire printed output in England before 1550!

Smyth is enamoured of the small printing press. This is not surprising since he has his own: 39 Steps Press, which he operates out of a barn in Oxfordshire. The most intriguing one he looks at was run by none other than Nancy Cunard, a rich heiress of the Cunard ship family. The link between Cunard and the Hogarth Press set up by Virginia Woolf proved pivotal in the history of the book.

Over tea on Virginia’s 33rd birthday in 1915, Leonard and Virginia Woolf had made three resolutions: to buy Hogarth House in Richmond; to acquire a hand press; and to get a bull dog. This was a defining moment in the history of the small, independent press, organized around the commitment of a return to the hand press, a refusal of industrial modes of book production, and for many later small presses, the belief in the importance of publishing radical literature that would otherwise stand no chance in print.

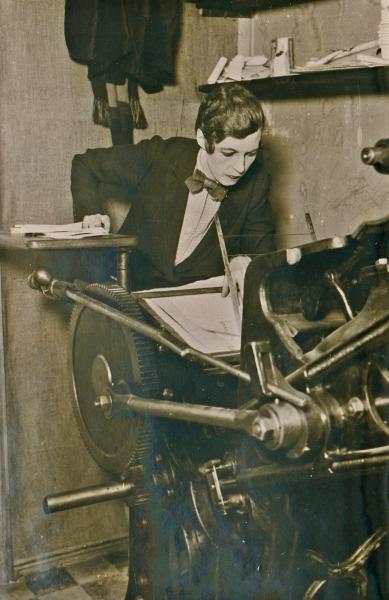

Fast forward a decade to 1925. Nancy Cunard landmark book of poetry, Parallax, was published by the Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Cunard was thus inspired to create her own press, dubbed Hours Press. On page 296 we see a startling photograph of Cunard, dressed like a male and wearing a bow tie, labouring over her press. One hopes she did not wear fancy dress clothes for anything more than this photo! Aside from the technicalities, Smyth gets to the heart of matter when he writes “Cunard found, like Woolf, a meditative calm in the process.” It didn’t last long: between 1928 and 1931, she printed 24 titles, all of them in runs of 150 to 200 copies. “Cunard’s memories of these times have a winningly chaotic quality, a sense of an enterprise held together only by determination and wit.”

There is a tremendous amount of information in this book, I am only scratching the surface here. But I will end by explaining my headline. It comes from page 186-187, where Smyth quotes the philosopher John Locke as describing the mind as “white paper devoid of all characters, without any Ideas.”

Smyth sees something Locke did not:

But despite the influence of Locke’s metaphor, there is no such thing as a blank page – not only

because claims of blankness miss the watermarks or the fibres or the chain-lines or the imperfections: presences which mean that writing is always an interruption of something already there, a disturbance in an existing order; it is never the beginning.

Once you read Smyth’s book, you will never look at any book (including this one, printed in a font pioneered by John Baskerville [1707-1775]) the same way ever again.

The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives is by Basic Books. It lists for $32.

Photo Caption:

Nancy Cunard at the Hours Press

Source: Musée du quai Branly