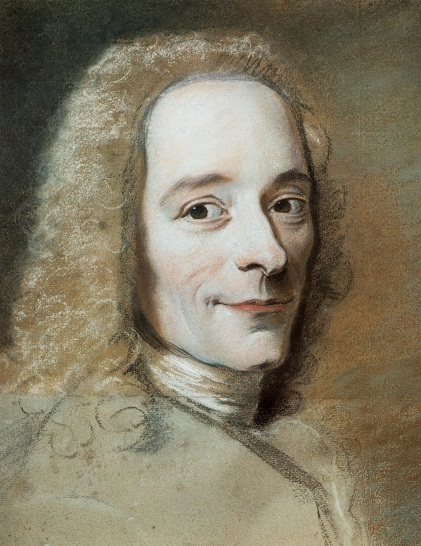

Image: Voltaire by La Tour

“Throughout the eighteenth century,” we are told in this book by Oliver Wunsch (professor of Art History at Boston College), “delicacy structured debates over morality, status, and power.” So, what is this thing called delicacy?

For that we must revert to the French word delicatesse, since the focus of this book is France in the 1700s. “The French term delicatesse principally applied to people, referring to a person’s sensitivity to subtle pleasures – a meaning rooted in the Latin delicatus. This idea of delicatesse occupied an important position within seventeenth-century French court society, where it signified an ineffable sophistication in behaviour and conversation.” Wunsch further states that he reserves use of the English word delicacy “for moments when material fragility is also at issue.”

The prime subjects of this delightful book are the actual works of art created in the 1700s. This is where the ‘material fragility’ comes into play. Painters often experimented with creating art in different media, but within a few years or even months, they began to degrade.

As an “extreme demonstration of delicacy’s aesthetic charm as well as its material hazards,” Wunsch examines the works of Antoine Watteau, whose working habits he describes as “reckless.” That he remains one of the most famous painters of the age is a matter of some luck, as many of his works ended up with “murky colours and gaping crevices.” The fact he died so young, just 37 in 1721, also has enhanced his legacy for the past three centuries. Like many of his artworks, Watteau himself was delicate, being physically fragile since childhood. All the more remarkable then, that he was able to capture idyllic charm better than anyone before or since.

Until Watteau, the “pursuit of durability” was a maxim every artist lived by. But the rulebook (which began in Paris in 1391) was thrown out the window in the eighteenth century, as artists strived for the ‘ineffable.’ This merged with the changing taste of the patrons of art. “They treated their collections not as inviolable memorials but as spaces in flux, selling works as readily as they bought them.” It is this synergy that is at the heart of the book, one that has never been thoroughly explored before.

To illustrate the subject of flux, we return to Watteau; , the author tells us that his 1716 painting The Pleasure of the Ball “changed hands no fewer than ten times.” As for the works he created, many of them perished noticeably day-by-day, according to one eighteenth-century account. The blame is largely attributed to the use of fatty oil, in which he wiped his brushes. Only the well-preserved minority of his works are famous today; Wunsch offers up several colour plates, showing details on various works that have been largely ruined. He set the stage for a new generation of artists to take even greater technical risks.

Maurice Quentin de La Tour became an expert of the pastel. “The medium’s physical delicacy took on a symbolic significance,” Wunsch relates, and the one he did of Voltaire in 1735 became especially famous (lead photo). “The picture’s delicate materiality, with all the airy lightness of champagne, perfectly instantiates the sensuous and momentary pleasures that Voltaire lauded.” But even the artists of the day realized how delicate their creations were. La Tour used “sturgeon glue for a means of stabilizing his work.” One writer in 1750 wrote that La Tour “became fixated on a varnish that he believes he invented and that very often spoils everything that he has done.” Pastel quickly lost its cachet.

But from the debris Wunsch recovers something worthwhile, namely an insight into “the central conflict of La Tour’s career: the struggle to reconcile an art based on lighthearted immediacy with the need to preserve that immediacy for the future.” No sooner had pastel faded from the scene (pun intended) than another craze took its place: encaustic. Unlike its ancient predecessor, the French version was a mix of wax with modern materials like turpentine, which proved unstable. Instability also affected the creation of sculpture. Wunsch closes with a chapter on the use of terracotta, another revival of an ancient usage, which was quite vulnerable to breakage. A few such works still survive, but none are in perfect condition.

A most intriguing look at the French art market of the 1700s, this is a beautifully produced book that should prove quite durable.

For the expert, the book is complete with 19 pages of notes, 26 pages of bibliography, and an index. Most illustrations are in colour.

A Delicate Matter: Art, Fragility, and Consumption in Eighteenth-Century France is by The Pennsylvania State University Press. It lists for $99.95.