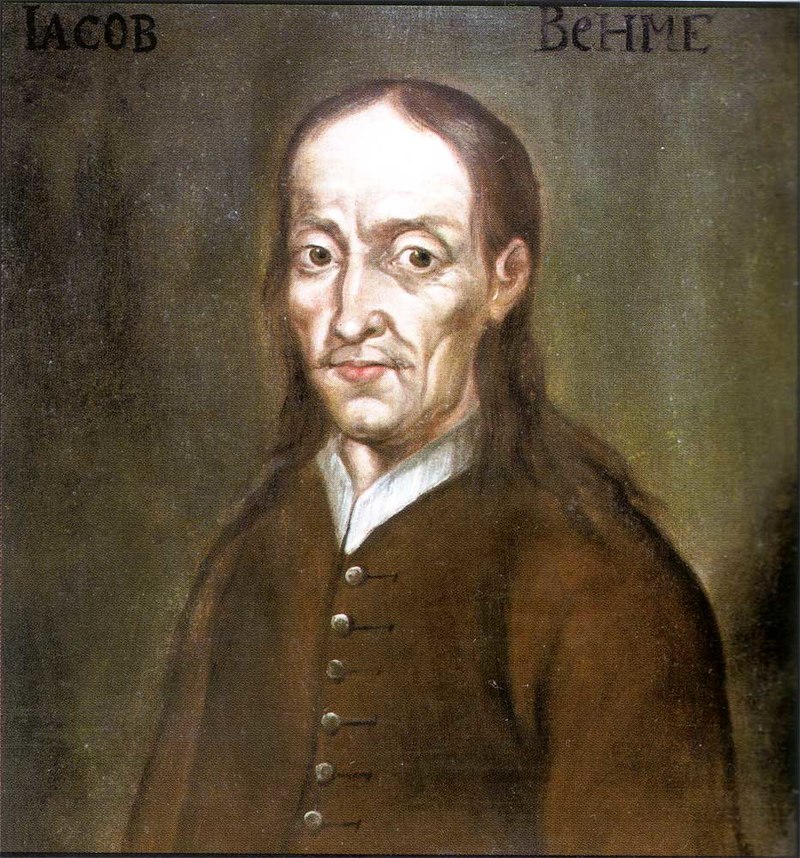

Photo: Jacob Boehme

I take the title of this review from a book title of 1650. It appears near the end of this fascinating book by Kevin Killeen, Professor in English at the University of York in England.

The 1650 book was written by Jacob Bauthumley, a radical religious writer in England. Before we continue, I must introduce the word apophatic, which appears 72 times in the book. Apophatic (or negative) theology describes God by what cannot be said of that deity. Many terms used to describe God’s attributes have an apophatic quality: when one states that God is ‘infinite,’ one is also saying that God is not ‘infinite.’

Bauthumley’s book was perhaps the most notorious apophatic book ever printed. In its pages, “God enacts his divine drama of heaven and hell in the landscape of the fleshy self, allowing God to be obscurely present even in sin.” In the words of Bauthumley, “sin is the dark appearance of God.”

As if this was not incendiary enough, he even transgressed the apophatic tradition itself. While it stresses the “fundamental inadequacy of language in encountering the divine…it insistently distinguishes itself from those it sees as genuinely unlearned.” But it was to those very people that Bauthumley addresses in his book. If such a thing happened today, no one would care very much, but Bauthumley had the misfortune to publish his book in the very year that the English government (in the grip of the king-killer Cromwell) passed the Blasphemy Act. Killeen tells us what happened: “It might be considered an irony that the punishment for writing a apophatic text on exquisite speechlessness was to have a hole bored through his tongue with a hot iron.”

Killen is an expert on this topic and time period, having written (in 2016) the book The Political Bible in Early Modern England. This new book is quite extraordinary, which I highly recommend.

Going back two centuries before Bauthumley, the author discusses Nicolas of Cusa, a German cardinal who “produced a dazzling set of variations on apophatic thought. Cusa’s most notable addition to the lexicon on the incomprehensible, in his On Learned Ignorance of 1440, was to mathematize the apophatic, finding paradoxes in geometry that characterize something about God.” Even Killeen is astounded by this, writing “That there might be a mathematics to our ignorance is in itself a dazzling coincidence of opposites.” I think he might have found a different word, as ‘dazzling’ twice in one paragraph is, shall we say, a bit dazzling. Nonetheless, his prose does get across to the reader the extraordinary nature of what was being seriously written, by a very high official of the Church, no less.

Killeen begins with the most famous apophatic text of all time: The Book of Job in the Bible. “Job demanded that Genesis be read as intractable,” Killeen tells us. With influence ranging from Milton’s Paradise Lost to the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, “Job serves, again and again, not merely to elucidate the cosmic mechanics by which the chaos and the nothing are wrenched into being, but rather to announce the inscrutable and the impenetrable nature of that process.” Heady stuff indeed!

Trapped in the Physics of the Universe

This book is quite literally “crackling with eternity.” This quote comes from Killeen’s look at the Mysterium Magnum, written by Jacob Boehme in 1623 (it was translated into English in 1654). Coming to the fore in England during the life of Cromwell (the traitor died in 1658), it cast a long shadow. Boehme’s critics called him mad; one said he put forth a theology “too ghastly, and even terrible to be uttered.”(Killeen devotes several pages to The Cry of a Stone, also published in 1654, which took down Cromwell in prophetic terms).

“Mysterium Magum,” writes Killeen, “with its vast scale, hovers between natural philosophy and theology. But it is neither.” It is, in fact, at the heart of the title of Killeen’s book: The Unknowable. Mysterium is a work of “theopoetics, understood as writing around and athwart the unreckonable and the unknowable.” Theopoetics asserts “wild poetic logic, which belies reason.” As an example, Killeen offers this quote from Boehme’s book: “The words of Moses concerning the Creation are exceeding clear; yet unapprehensive to reason.”

Boehme even accuses Adam as being the cause of the Tree of Knowledge, an accusation unique in literature. “Boehme has Adam trap himself in the physics of the universe. Because God knew Adam would fall, he was always already fallen. The fall was asequential, eternal.” An entire (and entirely brilliant) chapter is devoted to a detailed study of what Boehme wrote.

While his grasp of the sources is impressive, he did not look at the Renaissance bishop and poet Marco Giromao Vida (1485-1566), who had a very important attitude towards imitators of Lucretius. Killeen does provide some keen insight into Lucretius, but he does not give us this quote from Vida, who warned poets to avoid those who “pour out and pile up all things in their verses, without method, without art, especially if it is unknown, hidden, and not suitable for the ears of the crowd, such as the secret motions of the radiant heavens.” Of course the reference to ‘the crowd’ is again in line with the apophatic idea of the ‘unlearned’ I mentioned earlier. And the ‘unknown and hidden secret motions of the heavens’ is a direct reference to the very topic of Killeen’s thesis.

Unique is a word that can describe Killeen’s book. Many writers of the past wrote entire books about matters that were unknowable. Why they even bothered is the question that immediately comes to mind. This book answers that question. Read it.

The Unknowable in Early Modern Thought is by Stanford University Press. It lists for $63 (hardcover) or $21 (softcover)

Image: Jacob Boehme (1575-1624). Portrait in the collection of Museum der Westlausitz, in Kamenz, Germany. In the public domain.