“Consider a performance of Wagner’s Parsifal. As you settle into your seat, you look over the program notes, likely to address the Grail legend that inspired the composer. Now imagine a different approach: instead, you get the text of The Waste Land. As the stage curtain opens, the music begins, and, as it unfolds, all that you see and hear is filtered through the words that begin with the cruelty of April, coursing through temptations and disappointments, scenarios of enticement and sterility, ending unresolved in fragments shored against ruin.”

In this excerpt from the book What the Thunder Said, by Jed Rasula, we encounter the modernist way of mentally embracing Wagner’ final opera, first performed in 1882. For those who have not read The Waste Land, it opens thus:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

In Parsifal we see the ultimate expression of Wagner’s solution to boring operas: endless melody. Before his time, most operas would be dotted with arias (some spectacular), but otherwise they would be filled with chatter that many in the audience found tedious. This was a welcome solution to those at Houston Grand Opera who were in for a marathon experience this past weekend. Its production begins at 6pm, and ends just before 11pm. And if you were a read diehard and wanted to attend the pre-talk, better be there by 5pm! The last time HGO performed Parsifal was the 1991-92 season, so for many it would have been their inaugural exposure to this complex tale of the Holy Grail.

It might seem at first glance that viewing Parsifal through the lens of a poem is misplaced, but Wagner actually based the opera on a poem from the early 13th century. It is a story of personal redemption before the namesake character, Parsifal, becomes worthy of the Grail. The opera can thus be approached by a method expounded in the 1970s by Paul Ricoeur, who “sought to describe the core meaning of metaphor by relating it to the language of re-description and to the metamorphosis of reality.” (Here I quote from the Italian philosopher Raffaele Milani, see reference below). Ricoeur “uses three terms: prefiguration, configuration, and refiguration.” This framework maps nicely onto the three Acts of Parsifal. In the first act, the prefiguration of Parsifal is presented to the audience as an uneducated oaf who doesn’t even know his own name. In the second act, Parsifal at last understands his mission in life; and finally in Act 3, Parsifal refigures himself not just as a knight of the Grail, but their King.

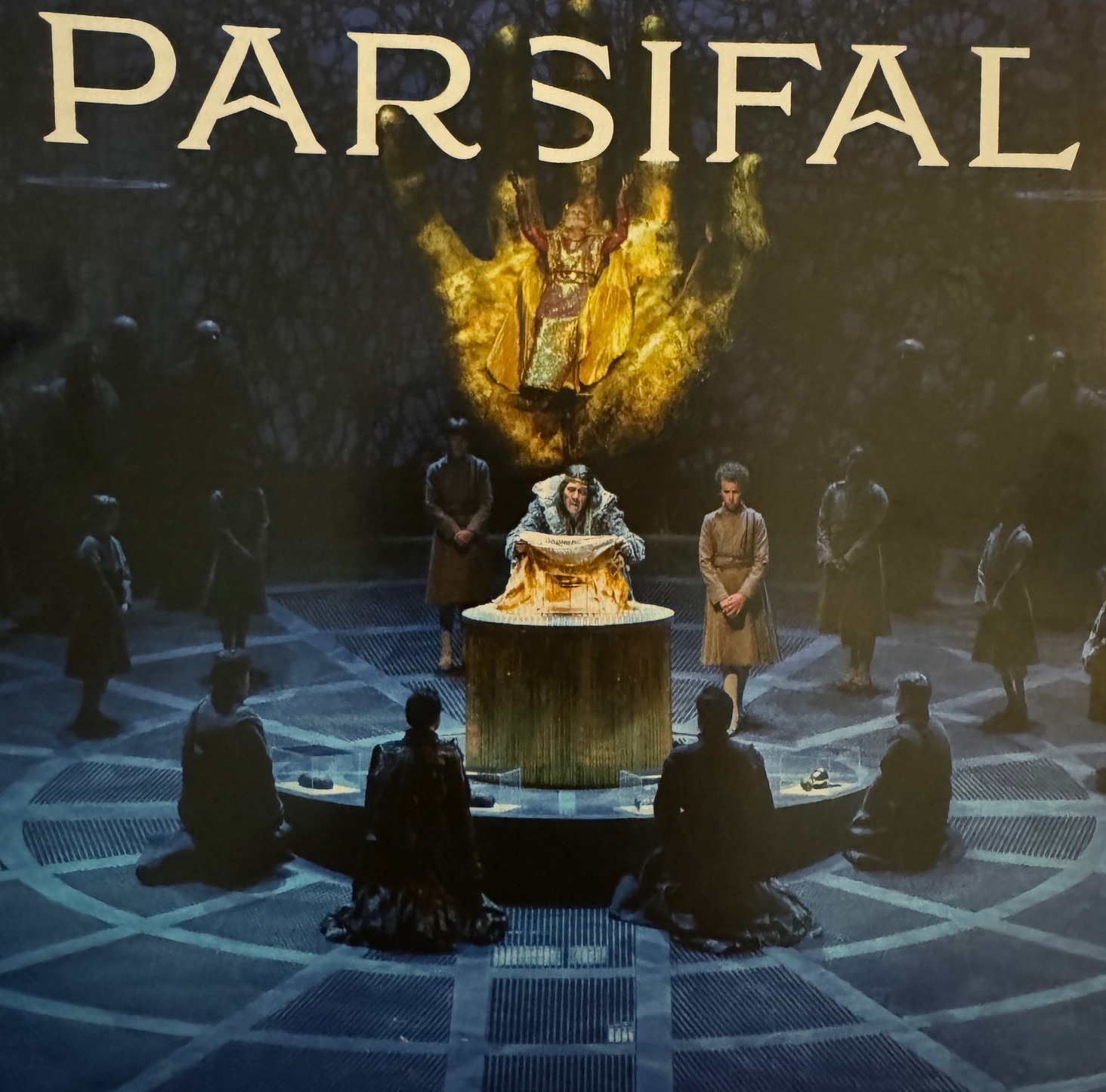

To say the production was spectacular would be an understatement. Houston Grand Opera has staged a performance worthy of The Met in New York, with stunning and at times deeply troubling sets. When we first meet Parsifal’s nemesis, Klingsor, we see him amidst a tower of red stalks that could easily double for Satan in his place of power. And the skeletal appearance of Titurel on a throne shaped like a gigantic hand was spell-binding in a very disturbing way – exactly what the role demanded. Kudos to the original scenic and costume designer Johan Engels.

I was close enough to see the expressions of the face of the cast; on display was a superb example of not just singing but acting. I will never forget the eyes of Russell Thomas (as Parsifal) at a moment of supreme crisis. No less dramatic was Elena Pankratova as Kundry, a spirit woman whose benign/dangerous influence is felt throughout the opera. She was the glue who held it all together in a bravura performance. Ryan McKinny as the King of the Grail Knights exuded just the right degree of passionate suffering without venturing into the realms of the maudlin.

If you have never ventured beyond our own excellent Austin Opera, I highly recommend making the trip to Houston. The two of them are amongst the finest treasures of our state.

Ref: What the Thunder Said, by Rasula, published by Princeton University Press in 2022.

Ref: Dawn of a New Feeling, by Milani, published by McGill-Queens University Press, 2022.