Winston Churchill is remembered by history for many things, including being the quintessential English politician and statesman. Therefore, it come as surprise to learn that he was actually a Member of Parliament for a seat in Scotland.

This book by Andrew Liddle, a political consultant based in Edinburgh, has actually managed to do something unique: he has written a book about Churchill that contains a lot of new material and insights. And it’s beautifully done!

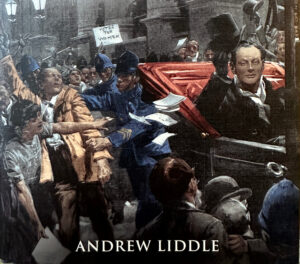

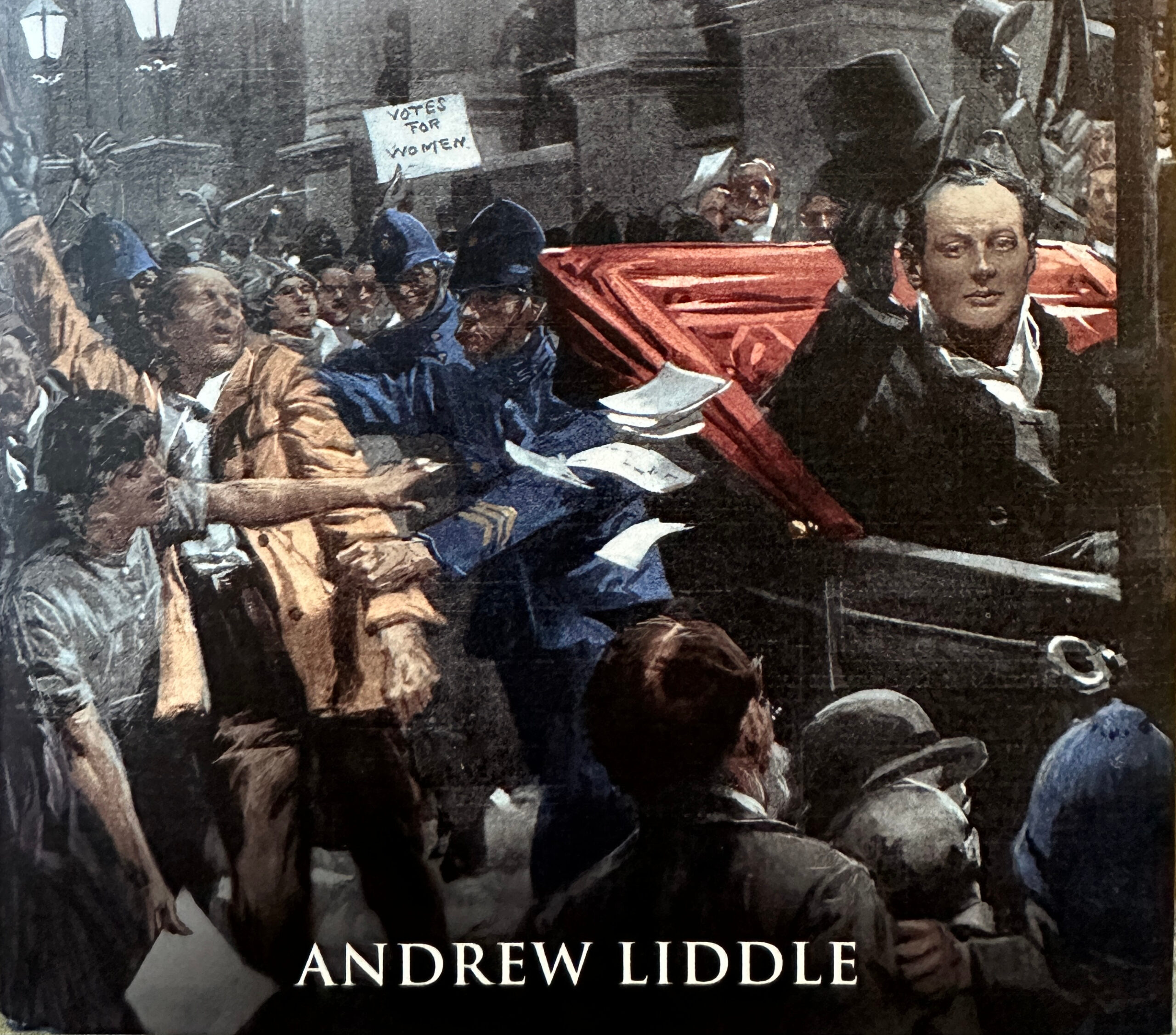

The cover illustration is a scene from the Illustrated London News on Churchill’s victory at the Dundee by-election on 9 May 1908. It shows him in an open car, doffing his hat at a mob frantically trying to get as close to him as possible. The police are barely able to control their enthusiasm (see the photo here). But in the background is a sign about votes for women. Liddle goes into some detail about why the suffragettes hated Churchill.

His Scottish connexion was actually due to a defeat. I imagine that while few know he was a Scottish MP, even fewer know he was an MP in Manchester before that! In April 1908 he was appointed to the Cabinet for the first time. This honour was accorded him by the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. The catch is that he had to submit to a by-election to take the post. As Liddle writes, “a handful of niche issues came to dominate the short but intense campaign.” In a word, he lost. As he thanked his supporters, he was handed an urgent telegram from the Liberal Party of Dundee asking him to represent them in Parliament. As Churchill himself wrote, “It is no exaggeration to say that only seven minutes passed between my defeat at Manchester and my invitation to Dundee.” It was the Churchill magic at work, once again.

The common thread running through this fascinating account of his years as a Scottish MP is the forlorn figure of Edwin Scrymgeour, a dour Scot who actually was a leader in the move to ban the consumption of alcohol. As any who knows the Scots, drinking anything other than alcohol was practically considered a sin (of course some like Edwin, were teetotalers). The remarkable thing is, he opposed Churchill in every Dundee election. Each time, he garnered more votes, and in 1922 he actually defeated Churchill.

While he admitted in an election address that he had little understanding or interest in local issues, Churchill based 15 years of his career in Dundee. Nonetheless, he did have his ear attuned to broader issues that affected Dundee. In 1908, for example, a thousand workers were without work when a national shipbuilding strike was called. He made a mad dash to London in the middle of his by-election campaign to join talks that might settle the dispute. “His efforts on behalf of Dundee works did not do unnoticed,” writes the author, and it certainly helped his election win.

The level of poverty and ill health in Dundee in these early years of the 20th century was horrific. Its child infant mortality rate was 174 in 1,000. “To put that in context, in 2019 the Central African Republic had the highest rate in the world at 81 per 1,000.” The author tells us “this had a profound effect on Churchill’s political life, adding impetus to his development as a Liberal politician.” He eventually embraced progressive social change, and introduced two important bills that passed Parliament. The Trade Boards Bill of 1909 allowed for the first minimum wage. It eventually included the jute industry: 37% of the population of Dundee was directly or indirectly employed by it. The legislation “proved so effective at raising pay in Dundee that by 1922 the city’s jute barons were lobbying Churchill to get it scrapped.” Also in 1909, Churchill tackled unemployment in the Labour Exchanges Bill. By early 1910 there were 98 exchanges established across the UK; they let the unemployed find work by connecting jobseekers with vacancies. William Beveridge was hired by Churchill to work at the Board of Trade, and went on to lay the foundations of the welfare state from 1945-1951. He praised Churchill to the skies, saying his period as President of the Board of Trade was a “striking illustration of how much the personality of the minister in a few critical months may change the course of social legislation.”

The book has many fine illustrations on 8 pages of B&W plates, but one I would like to have seen was a cartoon in the Dundee Courier newspaper in 1910. A day before nationwide polling opened that year, it ran a front-page cartoon under the headline Winston Back Again. “It showed a prostrated individual representing ‘Dundee Liberalism’ bowing at the feet of Churchill.” The cartoon was not one of praise. It intended to show that the MP for Dundee was too busy to visit his own constituency. But, as Liddle observes, this was shortsighted. Churchill had to campaign in marginal seats to get more of his own Liberal MPs elected, “thereby increasing the likelihood of returning a Liberal majority.” He won his own election, but the Liberal party lost many seats and only clung on to power with the support of Liberals and Irish Nationalists. For Churchill, it was not just a win, but a promotion. Asquith promoted him to the key post of Home Secretary, the youngest one since 1822.

The 1913 election saw Churchill make a great prophecy about the future government of the UK. “I prophesy that the day will most certainly come when a federal system will be established in these islands which will give Wales and Scotland control of their own affairs.” That is the system that has been in place since 1999. He actually made the proposal in a cabinet memorandum of 1911, nearly a century before it was enacted!

During World War I, Churchill was out of office and with the troops in France. But not just any troops: he was put in command of the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers. While it took a while to persuade these Scottish fighters that he was suitable for the job, he let his true feelings known to only one person. In a letter to his wife, Churchill confided “You know I am a great admirer of the Scottish race.”

While the public was accustomed to the animosity between Edwin and Winston, our canny author reveals it was not quite so clearcut. Churchill was back as an MP in the 1918 election, and in 1919 he was part of the British delegation to the conference in Paris that decided how to carve up Europe in the wake of victory. Edwin decided he would go there as a journalist, but he was unable to get credentials. Who did he turn to for help? His supposed foe Churchill.

“Reading his speeches and articles” about Churchill, “it is easy to perceive nothing but hostility bordering on contempt. Yet he clearly thought enough of Churchill to seek him out in his time of need, and to be genuinely grateful for the assistance, offering him his ‘heartiest thanks.’ In fact, the whole episode suggests they had a more genuine and respectful relationship than has previously been assumed.” When Edwin finally defeated Churchill 4 years later, the jolt was real, but he would still praise Edwin in his memoir Thoughts and Adventures. “I felt no bitterness towards him. I knew that his movement represented after a fashion a strong current of moral and social revival.”

Liddle also does a great service here in debunking what were allegedly Churchill’s parting words to Dundee. I won’t repeat them here as they were fake news.

This is a really fine book, one that will appeal not just to those interested in Scottish history, or Churchill’s early career, but for anyone who loves a David and Goliath fight scenario. Of course in this case, Goliath lived past a 1922 defeat to fight another day. In that final battle, he defeated Hitler and saved both Scotland and England.

Cheers, Mr. Churchill!: Winston in Scotland lists for $29.95. It is by Birlinn.