This biography of space shuttle astronaut Bruce McCandless is written by his son, of the same name. They are distinguished by Roman numeral. The astronaut is II, and his son is III.

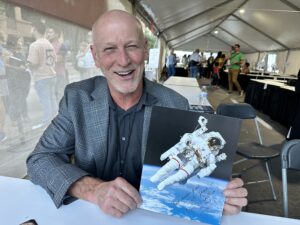

Bruce III was in Austin a few months ago at the Texas Book Festival, as shown in the photo, to discuss this book and his father’s life.

Bruce II was born in Boston in 1937 and died in 2017. There was a touch of the Old West in his background though. “My dad’s great-grandfather was killed in 1861” by a man who would later become famous: Wild Bill Hickok. The author does not say where this happened, or why David was killed, thus missing on the very first page a golden opportunity of spinning a yarn that would engage nearly every reader. It actually happened in Nebraska, and the interested reader can look up the details on the internet. David’s grandson Byron was in the navy, and was given command of “America’s most important destroyer base during World War II.” Again, we are left wondering where this was.

Moving up to his father, Bruce III relates he was living in Hawaii during the attack on Pearl Harbor. At that time Bruce II was four years old; his father, Bruce I, was a junior officer serving on the heavy cruiser USS San Francisco, and saw action in the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. With all this military history in his family, it is no wonder Bruce II was thinking of a naval career on a submarine. He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1958, and while he did not become a test pilot, he did land aircraft on carriers. One time in 1961 it did not go well, but he parachuted to safety before the plane ditched in the ocean. Investigation revealed a material flaw in the plane, so he was exonerated of responsibility. “When I was growing up,” relates Bruce III, “my father was reluctant to discuss this event.” Indeed, the father was reticent his whole life, which made writing this biography quite a challenge.

Even though he appeared intent on a naval career, that was not the case. “If it hadn’t been for the launch of Sputnik in 1957, he would never have become a pilot and go on to become an astronaut,” Bruce III said during his appearance in Austin. “He had his heart set on becoming a submariner: at the time he was really impressed with America’s first nuclear submarine, the Nautilus. It was a tremendous of engineering in its own right. When Sputnik was sent up it really changed his whole career path.” Bruce II got his MS degree in electrical engineering in 1965, and soon after that joined the astronaut corps, even though NASA was not accustomed to hiring engineers as astronauts.

“As I write in the book, a big part of the story of my Dad was the long period of waiting for a flight. He got in right at the end of the Gemini program and didn’t get a flight in the Apollo program or even Apollo-Soyuz. He got very frustrated; part of the problem was he was not a test pilot like the early astronauts and he wasn’t really a scientist like some later astronauts were. So he got stuck in the middle.”

This led to a tense family life. In the book, he writes “My father was dark and focused and generally on his way somewhere else.” In Austin, he gave a hint as to what it was like at home as year after year went by with his father never getting to fly into space. “He waited a really, really long time to get a flight [he waited from 1966 to 1984], but he persevered. It was always hard to know who would get the next flight, and why. He had some frustrations with that. We had a fairly small family: 2 kids and 2 adults, and we felt the frustration with him. There was a pretty steady diet of space news at the dinner table. Oddly enough I wasn’t particularly interested in space while growing up.”

This led to a tense family life. In the book, he writes “My father was dark and focused and generally on his way somewhere else.” In Austin, he gave a hint as to what it was like at home as year after year went by with his father never getting to fly into space. “He waited a really, really long time to get a flight [he waited from 1966 to 1984], but he persevered. It was always hard to know who would get the next flight, and why. He had some frustrations with that. We had a fairly small family: 2 kids and 2 adults, and we felt the frustration with him. There was a pretty steady diet of space news at the dinner table. Oddly enough I wasn’t particularly interested in space while growing up.”

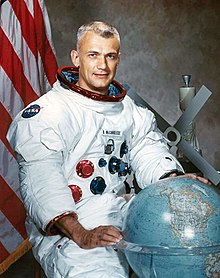

Bruce admits his father (pictured left) was hard to get along with, and tells us that a female astronaut (not named) thought that while he was smart, he “could also be abrupt, self-absorbed and prickly.” Bruce III says his mother has a theory “that my dad was simply too brainy – or possibly too nerdy – for his own good. The other astronauts were jealous, she said, because he was smarter than they were. I find this unlikely, given the intellects and aptitudes involved in the space program.” His mother, Bruce III relates, also blamed herself. “She wasn’t a good astronaut’s wife, she speculated.” Clearly, he lived in a troubled household.

The idea that led to Bruce getting his first flight actually originated in the 1920s, when Buck Rogers used a jet-propelled jetpack. Taking that from the comics to reality took most of the 20th century. The author details all the ups and down of the development of what became known as the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU). As the book lacks an index, the reader who really wants to understand this development needs to make notes.

In Austin, Bruce linked the early idea of the MMU with his father’s stalled career. “Another problem was NASA didn’t really like the idea of a jetpack flying outside of the spaceship. You could lose someone that way so it was sort of a cowboy thing to do. It took a long time for NASA to think it might work and he had to do a lot of that advocacy himself. Initially when the tiles of the shuttle were falling off the shuttle, he promoted a crewman on the orbiter to be out there with the MMU to inspect the orbiter for damage. That didn’t prove to be a very good idea and NASA fixed the problem another way.”

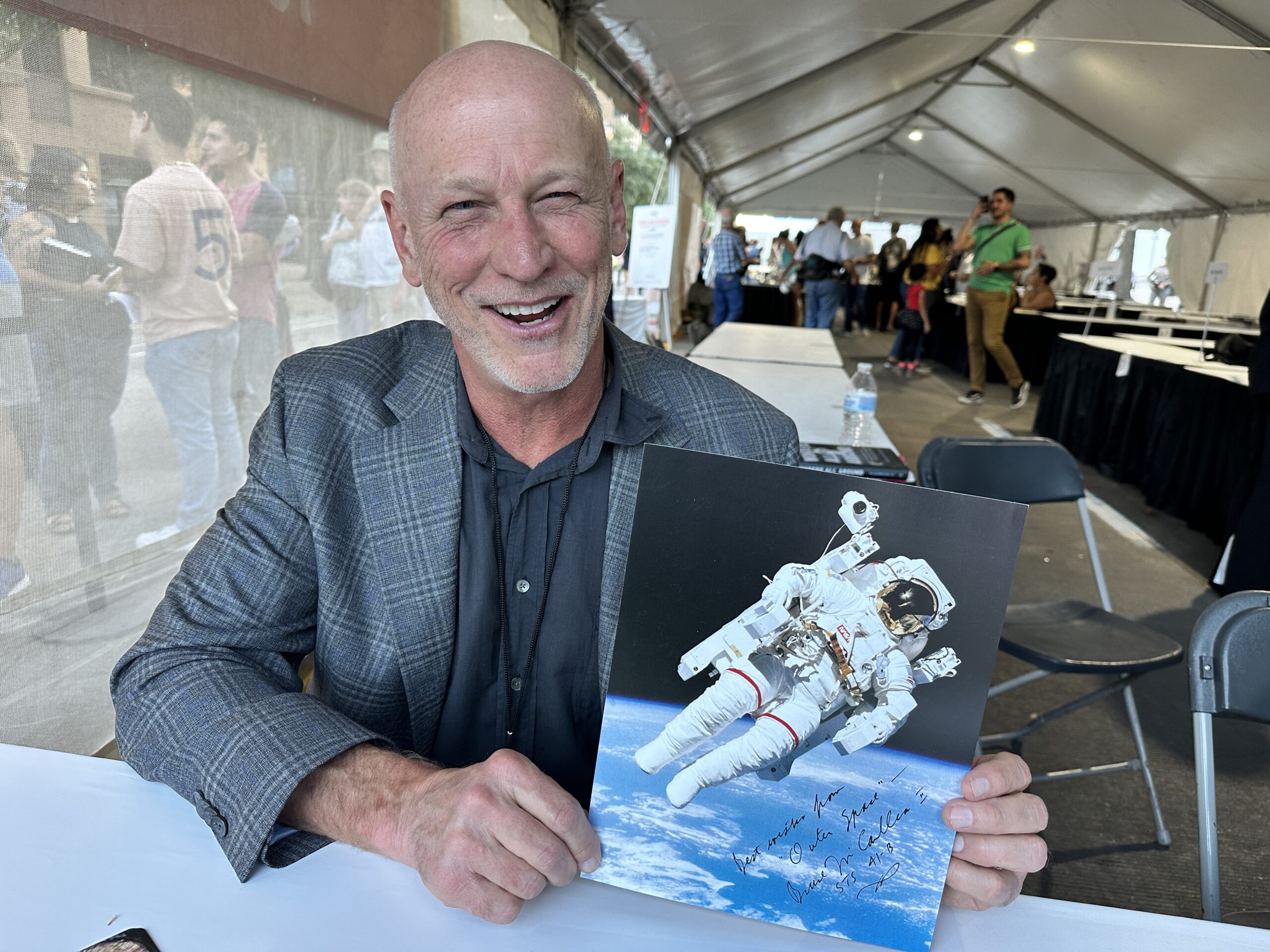

Once it finally got the green light, “The MMU captured the public imagination,” he writes. “It’s a machine people like to believe in.” The first flight of the MMU, with Bruce II in control, happened 7 February 1984. It “guaranteed him a spot in the pantheon of space explorers as the world’s first human satellite.” For the first time, a human was not tethered to a spacecraft during a so-called spacewalk. In the MMU, he was free to fly independently.

But the MMU had a short operational life. Later in 1984 it was used in an attempt to repair satellite called the Solar Max. “The satellite had malfunctioned and he was able to convince NASA this was the perfect opportunity to take the MMU out, grab the satellite and either repair it or bring it back to Earth.” The MMU worked fine, but the astronaut on that flight could not connect with the satellite because “of a tiny metal grommet the manufacturer had neglected to note on its blueprints.” In the event, the shuttle’s robot arm was used to capture the satellite, and that became the preferred method in the future.

“The MMU turned out to be a fabulous flying machine,” Bruce said in Austin. “It lives on in the form of the Safer device that the astronauts wear at the International Space Station (ISS). He had a lot of tribulations in his career, but he was happy to be the first person to fly that thing.”

Bruce II finally left NASA in 1990 to work with Martin Marietta, which had built the MMU. Over the next few years he contributed to major projects, including the Mars Polar Lander. The first one was lost in 1999, but Bruce figured out why, and the second attempt in 2008 succeeded. He formally retired that year, but kept working for Lockheed Martin until 2014.

This is truly the inside story of the life of an astronaut: a tale of unremitting study and labour at the cutting edge of technology. And while the author admits his father’s “inner life remains a mystery,” enough light is shed in this lovingly conceived account to make it a very worthwhile read.

Wonders All Around: The Incredible True Story of Astronaut Bruce McCandless II lists for $24.95. It is from Greenleaf Book Group Press.

Photo: Bruce McCandless III in Austin, holding a photo of his father in command of the MMU, in Earth orbit. Photo by C Cunningham