“Editing is not merely a scholarly exercise of compiling information. It is a rhetorical art.”

This statement comes from Kate Bennett, one of the 14 experts who have written chapters for this deep dive into the world of 18th century literature.

The book is edited by Melvyn New (Professor Emeritus, Univ. of Florida) and Anthony Lee (Visiting Professor, Arkansas Tech University). They and the other dozen scholars have produced a truly extraordinary take on the apparatus that forms the framework of other books on literature. Depending on the author and the publisher, this framework may be partially obscured, but without it the meaning of the text will be even more obscure.

As is appropriate in a book about footnotes, the ones in this book are well worth reading. Consider this from fn 9 on pg 9. Speaking of internet search engines, New writes in the Introduction “As with nuclear fission in the twentieth century, the twenty-first century will have to separate the constructive and destructive uses of this new source of energy – the World Wide Web is too much with us and Googling or tweeting we lay waste our powers.”

In the chapter by Bennett (Magdalen College, Oxford), she puts very cogently what the goal of annotation is. And once again she raises it to an ‘art.’ “Annotation is an art of brevity and of restraint. Yet where possible, notes should be a delight, putting pressure on details to produce a critical art in miniature.”

While many people regard footnotes with disdain (mere clutter at the bottom of a page, or sometimes well over a hundred pages of notes relegated to the back of a book), Bennet reminds us that “Most annotators allow themselves a little playfulness, a moment of participation in the world of the text.”

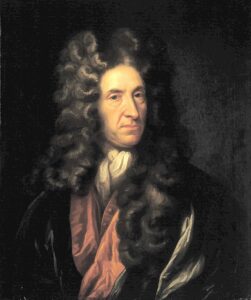

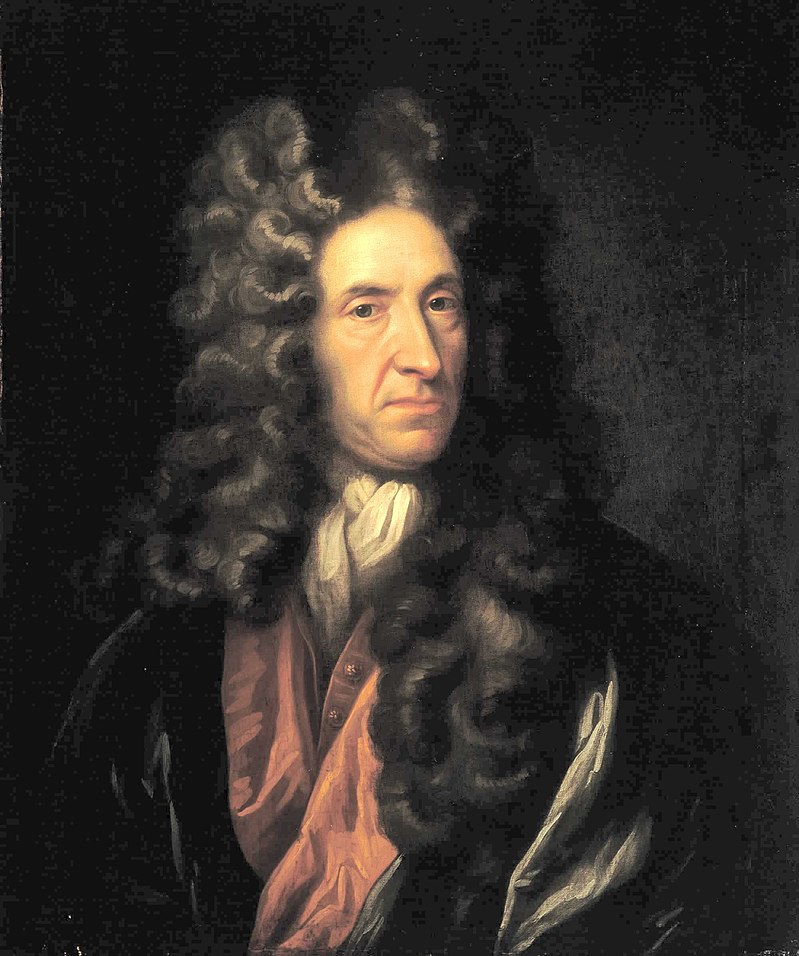

As I have found in my own annotations to the Collected Correspondence of Baron von Zach (7 volumes to date), tracking down an allusion from centuries ago can be most difficult. I spent 18 months on one footnote, but Maximillian Novak (Univ. of California, LA) relates an even worse instance in his edition of Daniel Defoe (pictured here).

“Defoe apparently believed that readers enjoyed filling in allusions in much the same way that moderns take pleasure in a crossword puzzle. Thus, he has an obscure allusion to the “Constable at Bow” – an allusion that neither I nor the other editors had been able to annotate.” It took Novak 20 years (!) to realise “that Defoe was free-associating two separate events having to do with self-defense.” One of these involved William Blackmore, the Constable of Bow, who was killed (in 1702) when he tried to “prevent the pressing of a citizen,” which means abducting a man in the street to serve in the Navy. Three years later, Defoe printed a letter in his journal, the Review, about another constable who was injured in a similar incident with a press gang. Novak writes rather ruefully: “I am not certain if this is an argument for taking time with scholarly editions, but in some cases it does not hurt.”

This relates to a provocative question posed by Thomas Lockwood (Univ. of Washington). “How many editors have entertained the criminal thought of silently walking away from a reference they were unable to identify or explain, without providing any note at all? Many, no doubt, including me…For the editorial majority who face up to defeat, the passive wording usual in such cases – ‘Not identified’ – itself tells a sad story of wishing to be as far away as possible from the scene of failure.”

Robert Hume (Penn State University) describes the unique issues involved in dealing with plays. He looks closely at Venice Preserv’d by Thomas Otway, performed in 1682; it had five production concepts. “One of the duties of an editor of dramatic texts with varied stage histories is to help latter-day readers understand the sometimes radically different performance potentialities in the text at issue. With very little textual adjustment, Venice Preserv’d has functioned effectively as a biting defense of authoritarian government but also as a strident call for rebellion against that authority.” Perhaps it should be restaged in New York during the upcoming trial of the former Dictator.

“Any ‘one size fits all’ principle of annotation cannot apply,” writes Hume. “Writers vary enormously in terms of the kinds of annotation required to make sense of their plays.”

He highlights the poor job so far done on annotating the musical aspects of drama. In a footnote, he mentions two great reference works on music used in plays before the year 1801. One was published in 1940, the other in 1957. “I have rarely seen these major resources cited in scholarship since 1970,” Hume laments.

Stephen Karian reminds us that annotation is a multi-generational experience; I would give as an analogy a slower-than-lightspeed spaceship sent to another planet, which would arrive 3 or more generations after the initial crew. “Each annotator strives to build on the accomplishments of predecessors in illuminating what has remained obscure. This collective effort, which connects annotators of the past, present and future, is foundational for literary and historical scholarship, and provides endless opportunities for genuine discovery.”

The question arises as to how a scholar decides which author to devote time to, and perhaps just one of the texts that person wrote. “The texts to elect to edit,” writes New, “how we edit them, and how we receive and make use of them – all these decisions underlie the health of humanistic endeavor, from the classroom to the scholar’s study.” I would expand this definition, as New is looking only at literary texts. Annotating the letters of scientists (such as Einstein, or the astronomer Baron von Zach) goes well beyond the humanities, and can offer tremendous insights into how scientific discoveries were made and what those scientists were really thinking as revealed in confidential communications with their colleagues.

New goes on to emphasise the importance of multiple readings. “Rereading will always be rewarded by further discoveries; one pass through, one set of eyes, is never enough to discover the full extent of the author’s involvement with another, and especially with favourite sources. Scholarly annotation opens rather than closes paths, indicating to attentive reads the rich veins of valuable ore worthy of further exploration.”

Finally, the reader must be wary of annotated editions. Not all are reliable! Anthony Lee writes in his chapter about Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Rambler that a “combination of abnegation of editorial responsibility and global tinkering (with Johnson’s text) renders the Yale edition suspect and untrustworthy to serious scholars.”

Lee quotes Dr. Johnson himself from 1775, “The greatest part of a writer’s time is spent in reading, in order to write: a man will turn over half a library to make one book.” In his role of annotator of an edition superior to that produced by Yale University, Lee presents a hope that must certainly be shared by all of those who labour mightily to create footnotes: that readers will be able to “apprehend the rich literary, historical, and cultural context” of the work in question “without having to turn over a library.”

A really fascinating look at a subject that few have given more than a passing thought to, Notes on Footnotes is a worthy addition to your bookshelf. More importantly, it should be on university English language course reading lists. Who knows, it might inspire someone to become an annotator.

Footnote. There is a typo on page 51: hits should be hints. Perhaps this error merits this annotation, but Bennett states that in her edition of the works of Aubrey “I did not correct the many errors in his Latin and Greek.”

Notes on Footnotes: Annotating Eighteenth-Century Literature is by The Pennsylvania State University Press. It lists for $119.95 (hardcover) or $34.95 (paperback).

Image: Daniel Defoe (1660-1731). Public domain image from National Maritime Museum, London