Can a mythical figure have a real grave?

That is the provocative question posed by Tomasz Mojsik in this book about Orpheus. Mojsik is associate professor at the University of Bialystok in Poland. The book, originally published in Polish in 2019, has wisely been translated into English so scholars worldwide can benefit from his research. In addition to the translation, 85% of the whole book has been reworked by the author, making it a scholarly text worthy of the great publishing house of Bloomsbury, which prints quite a few books annually in this identical style and format: small monographs of roughly 200 pages. They typically are positioned as a means to infuse novel and often contentious insights into classical scholarship, and I have found them to be among the most important books at the cutting edge of research into ancient history.

Orpheus was envisioned as a legendary figure, the first poet and musician. He was so adept in music that he could charm the animal kingdom. The most famous tale surrounding him is his trip to the underworld to retrieve his wife, surely one of the most romantic (and tragic) tales of all time.

Regarding the question in my opener, I quote the author: “The answer is yes. It was not a rare occurrence in ancient culture.” Orpheus actually had two tombs: first in Leibethra, where a tomb had been built in the fourth century BCE or earlier; and when that place was ruined it was transferred to the nearby Dion. Both are in an area of Macedonia known as Pieria, and both are close to Mt. Olympus, home of the Gods. In addition, there are myths surrounding his head: “Myrsilus speaks about a tomb of Orpheus’ head in Antissa on the island of Lesbos.” Like Leibethra, Antissa was destroyed; its residents then took the tomb with them to Methymna in 167 BCE. With all these locations and moves, sorting it all out is a major issue, which Mojsik ably tackles in a chapter-length analysis.

The tomb in Leibethra is perhaps the most famous of all ancient tombs, as it was visited by Alexander the Great. Mojsik quotes from Plutarch, stating the image of Orpheus at Leibethra, which was made of cedar-wood, “sweated profusely” in the presence of Alexander. “Most people feared the sign,” writes Plutarch, “but Aristander bade Alexander be of good cheer, assured that he was to perform deeds worthy of song and story, which would cost poets and musicians much toil and sweat to celebrate.” Mojsik tell us that “Sweating statues are a relatively frequent motif in ancient tradition and are linked with unusual events.” (Classical Macedonia, which is where Alexander the Great was from, arose after the Thracians were expelled from that area just north of Classical Greece).

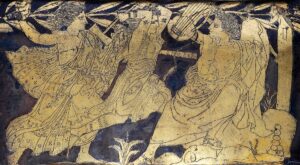

The emergence of the tomb at Leibethra is described by a writer who lived during the age of Augustus in the late first century BCE. While we know nothing about Conon, he wrote “a collection of erudite excerpts from the works of his predecessors containing fifty narratives of the mythical and heroic period. Most of them are obscure local myths and legends, and more than fifteen are foundational myths. Conon relates that Orpheus was killed by women (Thracian and Macedonian), and in consequence an oracle orders his head to be buried. “So they took it,” Conon writes, “and buried it under a large mound, and enclosed it with a sacred precinct that for a time was a hero-shrine but later came into vogue as a temple. For it is honoured with sacrifices and all other things with which gods are honoured; but it is completely forbidden for women to enter.” The death of Orpheus at the hands of crazed women became a standard motif in ancient Greece, and was even depicted on a cup known as a kantharos (shown in the lead photo).

As mentioned, the tomb of Orpheus was in Peiria, and his association with that region is the central focus of Mojsik’s book. “Tying Orpheus to Pieria may allow us to restart the discussion on the role and extent of propaganda in Classical Macedonia…Until now no attempt has been made at a detailed analysis of this Macedonian tradition.” In this book, Mojsik succeeds in his goal of including “all heretofore disregarded and scattered accounts,” which allows him to “reinterpret some known testimonies, and link them to information about the grave and cult of Orpheus in Peiria.”

Early in the book he quotes the epitaph that reportedly appeared at the grave of Orpheus

The Thracians buried Orpheus here, the minister of the Muses

Whom lofty-ruling Zeus slew with the smoking thunderbolt

The dear son of Oeagrus, who taught Heracles

Having discovered writing and wisdom for mankind

Mojsik uses this text at a platform to explore the contradictory details of the life of Orpheus and his reputation in Athens. According to the epitaph he taught Heracles (Hercules) “which was usually attributed to Linus,” and his “death at the hands of Zeus rather than Thracian women.” Zeus was said to have been angered when Orpheus divulged secrets of the gods to mortals.

Mojsik concludes this epitaph was most likely invented by the sophist Alcidamas in the 4th century BCE, but it had a domino effect. A certain student of the rhetorician Isocrates, Androtion (410-340 BCE), took this to mean Orpheus was a Thracian, who were widely regarded by Athenians as illiterate warriors. As Androiton explained, he “could not be the ‘inventor’ of wisdom, but should also not be the mythical predecessor of Homer and Hesiod.” That is, he could not have been the first poet! Mojsik identifies this as a crucial. “Importantly, this portrayal of Orpheus should be considered in the context of our knowledge of the Athenian’s contacts with Thrace in the fourth century BCE. The criticism of Orpheus served to strengthen the standing of Athens’ mythical musician, Musaeus.” Mojsik concludes that the “image of the hero as a Thracian appeared entirely as a mythographic, quasi-historical construct. Key changes to his image are a late first-century product.” The real benefit of this study, however, are fascinating “explorations into the origins of music and literature, and, more broadly, Greek culture.”

The story of Orpheus is not just an obscure and isolated matter that only classical historians are interested in. Many musical compositions have been inspired by him, beginning in the 13th century; more recent examples are Liszt’s symphonic poem Orpheus (1854), Offenbach’s operetta Orphee aux Enfers (1858), Stravinsky’s ballet Orpheus (1948) and most recently Fabio Mengozzi’s electronic poem Orpheus (2022). There are also many instances in film and literature, including Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus (1922) and the novel Orpheus’ Temptation by Stefan Calin (2020). Mojsik does not mention any of these examples, but he does write on the 1959 film Black Orpheus, where the hero accidentally kills his wife by electrocution: a modern take on her original demise. “The key reason for the endurance of the Greek myth in European culture,” writes Mojsik, is that it “is distinguished by its exceptional literary rendition and narrative fluidity.” As a key element of that myth, Orpheus does indeed permeate Western culture; Mojsik should be commended for bringing clarity to the varied origins and reception of Orpheus in ancient Greek times.

There is a typo on page 80: simple should be simply

Photo: The Death of Orpheus, detail from a silver kantharos, 420-410 BC, part of the Vassil Bojkov collection, Sofia, Bulgaria. Women at left attack Orpheus, who is holding his musical instrument. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Orpheus in Macedonia: Myth, Cult and Ideology (9.5 by 6.25 inches) is by Bloomsbury. It lists for $115.