Leonard Bernstein recorded it three times. Several distinguished critics have concluded it is a failure.

Whichever side of the fence you are on (and few indeed can be found sitting on that fence), the Austin Symphony Orchestra took the proverbial bull by the horns and gave us Mahler’s Song of the Night.

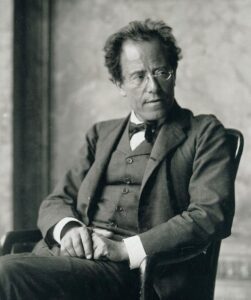

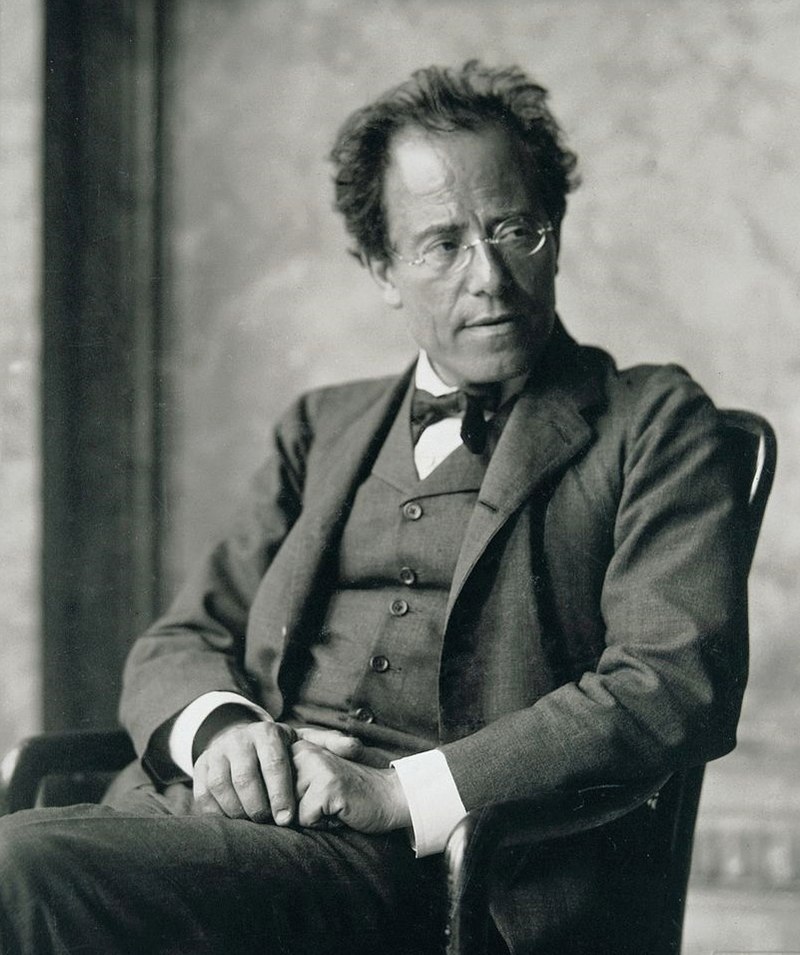

That title was not bestowed by Mahler on his Symphony no. 7, but rather by his own publisher who considered its first four movements dwelt in the darkness. Mahler composed it in 1904-1905; his photo here is from 1907.

To quote from the Mahler Foundation website, Dr. Hans Redlich (a famous scholar of Mahler’s music) believed “the symphony’s main problem is its lack of cohesiveness. He contends that the five movements do not relate to each other, but stand independently in marked contrast, despite feeble attempts at thematic connections, for Redlich, the symphony simply does not create the world Mahler claimed, was the touchstone of his symphonies.” I agree with Redlich, but taken individually the movements are quite fine.

In this review I’ll use the capsule summaries of each of the five movements to open my discussion. This is the first time Mahler’s 7th has been performed in Austin. While this is most welcome, it might better have been saved until Halloween.

First Movement (the mystery, beauty and longing of night). It opens loud but sprightly, with a sprinkling from the horn section that gradually becomes more dominant and eventually stentorious. Suddenly it becomes quite calm with a bird-like quality, followed by a dreamy passage enhanced by 2 harps. It has a lush, romantic feel, akin to a paradisical setting. This flows into an expansive and brilliantly noisy evocation of Paradise Regained. A tremendous first movement.

Second Movement (its apparitions set in a Night March) Horns and violins set the pace here, and if think you are hearing cowbells in a symphony, you would be correct!. A poky, meandering movement that soon morphs into a sweeping melody that unexpectedly ends on a ping.

Third Movement (a shadowy and macabre world of superstitious terrors that haunt the night) For me this evoked the fateful night in Howard’s End where Helen and Henry argue about how Henry ruined the life of Leonard Bast, who dies soon afterwards. The sense of impending doom is palpable in this movement.

Fourth Movement (a nocturnal serenade) Another unexpected instrument makes it only appearance here: a mandolin (situated behind the violin section). With its very un-symphonic sound, the mandolin sets the agenda for the movement, entirely by itself at key points. It steers the orchestra to shift course as it navigates through this contentious score.

Fifth Movement (release from the night with the morning bells ringing in bright day) The final movement is out of the gate at a full gallop. This 15-minute movement is a fast-paced and full-throated race to the finish line: complete with bells, horns and drums. The cacophony of ultimate victory is spine-tingling. The walls of the Long Centre were literally shaking as maestro Peter Bay drew this remarkable symphony to a close.

Visit the website for future concerts: austinsymphony.org