“War, peace and international affairs: Montesquieu’s writings are essential to our understanding of America for the past 250 years.”

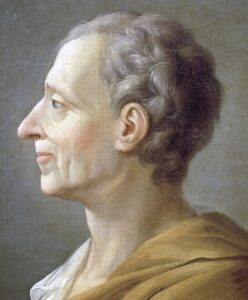

Dr. Paul Carrese (Arizona State University) is an authority on the works of Montesquieu (1689-1755), the French political philosopher whose writings are fundamental to the American experiment. He recently gave a talk in Austin, sponsored by the Civitas Institute and the Clements Center for National Security at UT Austin.

Montesquieu believed in a law of nations, rooted in the principles of natural justice and human nature. It is the belief of Carrese that he has in a sense been the light at the prow of the ship of state as it has sailed through the centuries. In still waters or rough seas, Montesquieu has been the guide.

Despite Montesquieu’s undoubted role, Carrese explained that it’s actually an uphill battle to convince everyone of that in the 21st century. “I have to acknowledge that this approach to Montesquieu and his importance in understanding international affairs and grand strategy – his deep influence on American strategic thinking – is rather strange or outlandish in academic discourse today. I’ll defend this by saying there’s been a small upsurge in Montesquieu and the American founding. I’ve been asked to present versions of this talk in the past year in Paris at the Sorbonne, and an international conference on law and social philosophy at Bucharest, and also to graduate students in a program based in Washington DC at the James Madison Memorial Fellowship Foundation.”

“The importance of Montesquieu’s philosophy and its American legacy is so strange because the dominant academic and policy debates about American foreign policy in the post-Cold War era have turned away from these core principles that had long informed American views of war, justice and peace. Rival camps today look either to the modern school of realism (traceable to Machiavelli and Hobbes) or to a modern school of liberal idealism (traceable to Kant).” Carrese sketched out a contrasting argument that from Washington and Lincoln through the Roosevelts, Eisenhower and Reagan, “the dynamic but enduring core of successful American foreign policies that has sought to balance sobriety in international affairs with an exceptional commitment to universal principles prioritising peace and stability.” Carrese identified the core text that supports this as Montesquieu’s right of nations, best encapsulated by the principle of enlightened self-interest.

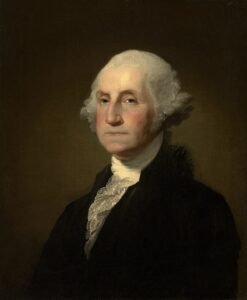

Washington’s Farewell Address

Eisenhower “thought that Washington’s approach of balance, enlightened self-interest and republican prudence was not at all outdated in the era of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles and the novel need to oppose a global totalitarian ideological alliance led by the Soviet Union. One proof of Eisenhower’s direct reliance on Washington’s principles arises at the close of his two terms when he decided his staff should review Washington’s farewell address as a template for preparing Eisenhower’s farewell address in 1961.”

It is striking that Washington, in the address, does not think only in terms of the country becoming a great power. “He was not following Kant or Machiavelli. It is rather an exposition of Montesquieu’s work.”

The presidency is a modern echo of a Roman consul, an echo that was first heard with Washington. Carrese explores the Roman antecedents in his 2003 book, The Cloaking of Power. He writes that in The Federalist, Alexander Hamilton argues that “the Constitution’s superiority to ancient republics rests upon the ‘great improvement’ achieved in the ‘science of politics’ in modern times. This bold claim reflects the complex, common-law liberalism of Montesquieu.” He also discusses the classics and American constituionalism in his 2016 book, Democracy in Moderation.

Montesquieu argues in his most important work, the The Spirit of Laws (1748), “that rulers and governments should strive to balance higher principles of right, guiding a decent (non-barbaric) politics with, on the other hand, practical realities of military defense against illiberal powers.”

Carrese related this to America’s first president, George Washington. “This approach in fact explains the opening statement of principle on international affairs in Washington’s farewell address. The farewell address is important because it’s the high consensus statement of many principles of American constitutional politics: perhaps most especially the grand strategy of foreign policy. That was evident immediately when it was published in 1796 and it’s been continually recognized as such by the most discerning of American thinkers and statesmen.”

It is also instructive to ask who Montesquieu looked to for his own inspiration. Montesquieu seems to have been particularly shaped, said Carrese, by the 17th century jurist Grotius who drew on classical and medieval sources to expound on international law. That was in his work of 1625. “Washington had a copy of that work in his library!”

Montesquieu’s Right of Nations

Since other models have failed to explain the ascendance of America, Carrese suggests “we turn to study Montesquieu’s philosophy of the right of nations and its spirit of moderation as the best guide to understanding of American policy and the prospect of a just international order.” But that is just what is ignored by modern scholarship. “Even for those who still study his philosophy of the constitution of liberty, his novel views about federalism and the separation of powers, almost none of that small subset anymore study his right of nations philosophy of war, peace, commerce and international affairs.”

Montesquieu “announces near the end of his The Spirit of Laws that moderation, or finding the reasonable middle ground amid extremes is the guiding principle of his political philosophy. Montesquieu’s blended liberal republican philosophy of international affairs shaped the sober but still liberal grand strategy and foreign policy established by Washington, Hamilton and other founders of the constitutional republic. By guiding American grand strategy across the centuries Montesquieu’s philosophy also ultimately shaped the sober, liberal world order sought by the Cold War American strategy, and actually achieved since 1991.” He expands on this in his book, where he writes “The role of The Spirit of the Laws and its legacy in developing a judicialized politics matters for only for American constitutionalism but for the liberal, democratic politics and law that have been dominant in much of the world since the collapse of communism in Europe.” With such liberal democratic politics under attack now, it remains to be seen if it can withstand the rise of rightwing ferment in Europe and the United States. Is the 250-year-old experiment about to fail?

In his talk in Austin, Carrese said “Montesquieu’s conception of the right of nations argues in some detail that a statesman must heed liberal principles while making the necessary adjustments about how to apply them. That is, find the least worst departure from them in difficult circumstances!”

It is important to realise that Montesquieu was the first philosopher to advocate for a liberalised global culture in international affairs. But, as Carrese stated, “his right of nations philosophy transcends this element, and is not in fact captured by any of today’s doctrines or schools of international relations.”

Carrese opined that the “enduring if implicit impact of his philosophy had the power to moderate the thinking even of American realists such as Henry Kissinger.”

The Danger of Philosophizing

However, we should be wary of philosophy, even political philosophy (that most practical of all philosophic enterprises). The problem with philosophy is that it is done inside the privacy of the mind, but the world exists outside the mind (so take that, George Berkeley!). Therefore, all philosophy is in some sense ideal. Montesquieu realized this danger of philosophizing, and in his great work Persian Letters, about two Persian men who travel to France, he tempers this idealism and rigor of philosophy with the realistic and less rigorous musings that a persuasive human personality brings to a story. Letter #68 of the book serves as a reflection on the nature of law, and it is particularly relevant to the so-called judicial liberal democracy that is America today. In the letter, one of the two main characters, Rica, writes a letter to Usbek, the other main character, about an experience he had at the home of a French judge. Towards the beginning of the letter, Rica recounts how he remarked to the judge that he had not seen the judge’s office. The judge responds that he does not have an office:

“When I took this position, I needed money to pay for it. I sold my library and the bookseller who purchased it left me nothing, from a prodigious number of volumes, but my account book. It is not that I miss them. . . .What need do we have for all these volumes of law? Almost all the cases are hypothetical and outside the general rules. . . .We have living books, and they are lawyers. They work for us and take it upon themselves to instruct us.”

[Translation by Prof. Stuart Warner and Stephane Douard, 2017.]

This passage is the heart of the letter and highlights two essential features of modern America: a too-broad disregard for legal tradition (that tradition being partly expressed in judicial restraint imposed by fidelity to written texts) and the increasing inaccessibility of the legal profession, i.e., its increasing jargonization—“Almost all the cases are hypothetical and outside the general rules”. To the former point, think of the idea of a living constitution, or as Montesquieu would have it: “living books.” To the latter point, this is one reason that people feel that there is less liberty in this country and that the people have less control over all aspects of government, that there is less self-government than ever before: because if we are a country of laws, and not of men, and the legal profession is increasingly inaccessible to the average person, in that the law-making process is the province only of trained experts, then necessarily politics would be similarly inaccessible.

That is the very reason populism, which is on the rise, exists—as a reaction against the idea that governance is the province only of experts (a specially designated political class). The American Founding is in some sense deeply populist: ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people’—echoing the sublime and very populist Roman maxim: Vox Populi, Vox Dei. One of the most anti-populist expressions of the modern legal profession and modern politics is judicial activism: judges who seemingly create laws rather than interpret laws, “legislate from the bench”; judges, who, to use Montesquieu’s language, “instruct us”, rather than interpret for us. The most famous, or infamous, example of judicial activism of the past 5 decades is Roe v. Wade (incidentally, Grotius is essential to understanding why abortion could never be a constitutional right.) And this phenomenon is not purely in the legal profession; the American government has an ever-expanding bureaucracy filled with federals who make law and policy outside of Congress. It seems that most of the legislative power is most definitely not vested “solely” (to quote the Constitution) in a Congress of the United States. Montesquieu awakens us to the importance of an accepted tradition to circumscribe the power of experts, even the best of them. Whether it be in law, through the common law tradition and written texts, or the political tradition, with legislative power being vested only in a Congress and the system of checks and balances—those “volumes of law. . . .[those] general rules” are the insurance-policy that the people take out on self-government.

[The analysis after the passage about Kissinger is written by SunNews contributor Conlan Salgado of Roosevelt University]

Photo credits:

Dr Carrese by Dr. C. Cunningham

Montesquieu: originally uploaded on en.wikipedia by Maarten van Vliet (talk · contribs) at 16 October 2004.

Washington: painting of 1803: Gilbert Stuart – https://www.clarkart.edu/artpiece/detail/george-washington