How about a good old-fashioned pumpkin horror story from Spain to get Halloween off to a fine start?

“Maria de Ulibarri, married, age 36, came before an inquisition commission in September 1611. Her goal was to discharge her conscience and remedy her soul. Ulibarri told the commissioner that three years earlier she had been lured into witchcraft by a single woman who also lived in Corres, where Ulibarri was residing.” The woman arrived at Ulibarri’s house in the late afternoon and “pleaded with her to attend a gathering. Ulibarri replied that she was wasting her time. In no way would she leave her house.” At this time, it was considered highly improper for a woman to walk around outside by herself .

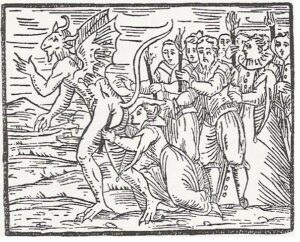

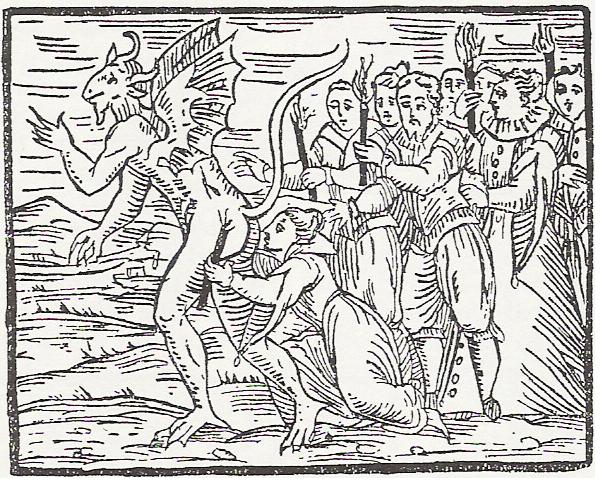

“The persuasions of the older woman had an effect, and Ulibarri eventually agreed to meet her at her home that evening. Once there, Ulibarri’s new friend took out a pumpkin, from which she removed some powder: with that substance she anointed Ulibarri’s breasts, belly, and shoulders and told her not to speak Jesus’s name or commend herself to God and His saints. At that moment, the two women rose off the ground, flew through the doors of the house, and without touching the earth, went to Islarra, half a league away. There the Devil was present, in the form of a man, seated on a throne, with two enormous horns on his head.” She proceeded to kiss his ass (as shown in this review from a book of 1608), and then later had sex with the Devil.

Ulibarri was ordered to come before an inquisitor named Salazar on November 29, 1611. “The confession was read back to her. She said that every word she had spoken was true.”

Scary stuff indeed! It is just one of scores of actual happenings in the Navarre region of Spain (bordering on France) four centuries ago, when witchcraft was (apparently) rampant there. Not just a few, but thousands of people were accused of being witches. Lu Ann Homza, Professor of European History at William and Mary College in Virginia, has taken a fresh look at all this in her new book. It is a fascinating and detailed study of a unique element in the witchcraft mania that swept Europe and New England.

“Navarrese culture,” writes Homza, “had long-standing, terrifying traditions about what witches could do. Modern historians have taught us to notice sex, age, and socioeconomic status in witch-hunting, but the Navarrese findings capsize our presumptions in these regards.” While scholars have become complacent about the archival records, essentially stating everything has been studies, Homza has discovered a large trove of documents that sheds a whole new light on the witchcraft trials of 1608-1614.

This is largely due to legal papers generated “when illiterate villagers turned to legal systems to help. Their astute use of the law to fix dishonor and achieve vengeance is breathtaking.” The dishonor happened when a person accused someone of being a witch. Quite often the dislike arising from a loan that had not been repaid was enough to accuse a person of witchcraft. Sometimes children accused their own mother of being a witch! Naturally, the person was not a witch, and was thereby incited to launch a libel charge, which resulted in an investigation and maybe a trial, a fine, or worse. For example, “one elderly woman had both her arms broken during court-sanctioned torture.” Sometimes village women took it upon themselves to root out witches in their midst. Homza tells of one incident in 1610 where 3 woman took an elderly woman to a parish church where they tortured her for more than an hour. After saying she would confess, the woman was then taken back to her home, where she refused to name any accomplices. The three women then tortured her to death.

The witch hunt moved into high gear in 1609. More than 70 people in one town had been accused of witchcraft, while in another, “a woman had turned 15 children into witches in only 8 days.” An investigation found “the Devil’s mark” on the accused. The witch hunt reached a crescendo in October 1610. On the 19th the tribunal announced “to great applause” that a spectacle would be held on Nov. 7. A procession of 53 prisoners arrived at the town square. After a lengthy reading of their sentences, six of the prisoners were burned alive. Others were sentenced to exile, or to live the rest of their lives in monasteries or convents.

As I mentioned, Navarre had a long history of witchery. The Spanish Inquisition was on the case. In 1526, the Inquisitor-General himself called a conference of 10 theologians to confer. Amongst other things they actually took a vote on whether or not witches could fly. The result was 6 to 4, in favor of the flying option!!

Into this mania of hatred and superstition entered someone who injected some sense into it all. The Salazar I mentioned earlier spent a lot of time in these villages, and reported back to the Suprema in Madrid that most of the witchcraft allegations were shot through with deception. He personally absolved many children. The Suprema took note, and in 1614 cancelled “every aspect of the five years of investigation.” Salazar “spent years defending himself from having undermined his own inquisition tribunal.” Homza notes ruefully that he became a member of the Suprema in 1631 as he “was ultimately incapable of reimagining his office or abandoning the presuppositions he inherited.” In writing this book, she has done a great service in finally (after four centuries) giving us the true story of the witch hunts in Navarre.

Another new book dealing with witchcraft goes much further back. Richard Kieckhefer, Professor of Religious Studies at Northwestern University, has translated two texts that give a marvellous insight into what people believed witches were capable of. The earliest text (1456) is the Book of All Forbidden Arts by Johannes Hartlieb; the second, from 1489, is On Witches and Pythonessses by Ulrich Molitoris. When one considers that these texts have essentially been locked away for more than 500 years, having them in English now is a great boon to the study of witchcraft.

The Hartlieb book has 132 brief sections that essentially answer any questions someone might have. They have titles including “How sorcery is carried out with many forms of water; “A lesson in how one can resist the Devil”; “How the Devil enters into people and possesses them”; “Certain books about the Black Art; and “How the flight through the air takes place.”

This last one has resonance with the vote of the clerics mentioned in Homza’s book. So how do witches fly? Hartlieb tells us: “They make it out of seven plants, and they pluck each plant on a day that is proper to that plant.” The author then lists the plants, but is coy about the exact formula. “With these they make an unguent, mixing some blood of a bird and the fat of animals, but I will not write it out, lest it bring someone into trouble. When they wish, they smear this unguent on benches or chairs, rakes, or oven-forks, and they fly away.”

Molitorus gives what might be a surprising interpretation of the power of those who believe they are witches. He says they are “sinful and foolish”, and that all the things they do to conjure bad storms and evil happenings is nonsense. The Devil teaches them to do these things, and when bad results happen, “these women then heap favour on the Devil, worshipping him,” when in reality the Devil himself made it all happen, or knew when something was going to happen. Kieckhefer tells us in his introduction that Molitoris “draws on scriptural, historical, literary, and legendary sources to show what witches are alleged to do is indeed possible, with demonic aid.” He compares the two books that are included in his translation: “The most obvious differences are in form and focus. Hartlieb wrote a vernacular survey of the forbidden arts that is on a superficial level tightly organized, while Molitoris penned a Latin dialogue on witchcraft with the more overtly rambling quality of a dialogue. They appropriate work uncritically, making little distinction between legend and history, fiction and fact, folklore and literal truth.”

The Melitorus book is noted for its woodcut engravings, seven of witch (pun) are included in this book.

Both of the books reviewed here are serious, scholarly additions to the literature of demonology, and deserve a place in any library dealing with the occult or late Medieval/early Modern history.

Village, Infernos and Witches’ Advocates, by Lu Ann Homza.

Hazards of the Dark Arts, translated by Richard Kieckhefer. This is part of the “Magic in History Sourcebooks” series.

Both books are by Pennsylvania State University Press.