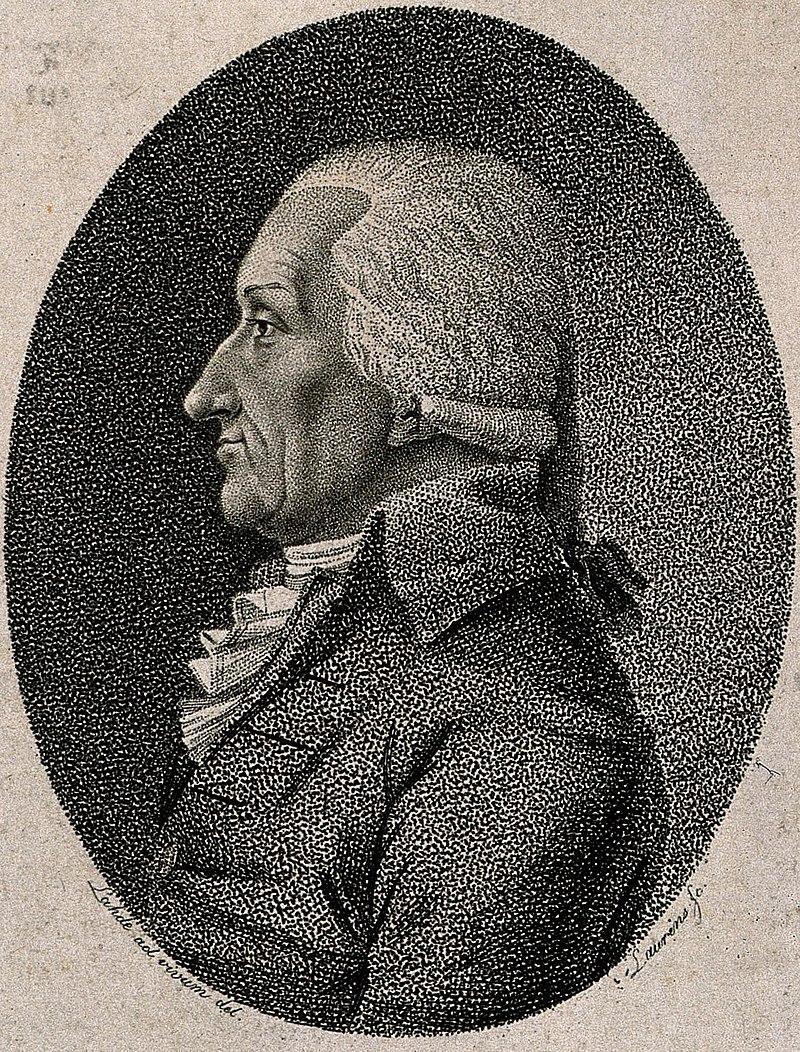

This book offers, for the first time English, some of the most important early writings by the great German philosopher Johann Nicolaus Tetens (1736-1807).

The first 36 pages consist of an introduction and analysis by the three editors; the next 240 pages contain a full translation of texts on language (etymology), anthropology, and the philosophical method more generally. It contains all of his key writings up to the publication, in 1777, of his most noted work, Philosophical Essays. Hopefully this and further texts will be made available in a forthcoming volume.

Each text is replete with dozens or scores of footnotes that are more than mere adornment: quite often the text cannot be properly understood without reading them.

Here I will comment selectively on the translated texts. The earliest one dates from 1759, entitled Thoughts on the Influence of the Climate on the Manner of Human Thought. As the editors correctly note, “Compared with other writers of the period, it shows a deeper understanding of the challenges posed by applying the scientific method to problems of anthropology.” Even so, Tetens’s use of a syllogistic argument (which the editors do not comment on) shows an unfortunate reliance on the Medieval scholastic approach to inquiry. The syllogism is given in the book on page 42:

“If the manner of thought of a human being is determined by his sensations; and these by the arrangement of the nerves; and further, the climate manifests its effects on the nerves; then its influence on the manner of thought in undeniable.” This leads Tetens to the tendentious assertion that “all inhabitants of a climate sense exactly the same.” Even so, he clearly distances himself from Montesquieu, who equated the drunkenness of people to the degree of latitude of countries, the condition being worse the farther north one goes. This, says Tetens, “is much rather a conceit of a great spirit, than it is a truth grounded upon a complete deduction.”

His 1760 essays, Thoughts on Some Reasons Why There Are So Few Settled Truths in Metaphysics, is really a dismantling on the entire metaphysical system. He asks a pregnant question: “How many new settled truths has metaphysics been enriched with since the time of Aristotle?” He concludes at once the increase in useful truth “is extremely small.” One reason why that is so “is the confusion and obscurity in the concepts from which the principles are composed, and which have an influence on their proofs.” He constantly compared metaphysics with mathematics, whose “truths are so clear to the understanding and so settled.”

Actually, his essay can better be seen as an exposition on mathematics than metaphysics, which he simply uses as a foil to show how useless it is. Tetens actually gets to heart of modern physics in his explanation of mathematical truths. “When mathematicians themselves ascribe the greatest distinctness to their concepts, this must be understood only relatively, namely, with respect to the proofs of the propositions. But their claim is not to be taken to mean that in the development of their concepts of such things there would not eventually be found something confused that cannot be developed further.” In modern terms, we encounter a black hole in space – a singularity – where the tools of mathematics reach their limit. The centre of a black hole is a well of confusion.

Tetens revisits this from another angle a bit later in his essay, when he says one must investigate the nature of simple concepts from which compound concepts are composed. “The important truth,” he writes, is “that our knowledge of actual things, whose concepts experience must teach us, is only capable of a certain degree of distinctness, in which there is always much remaining that we cannot represent otherwise than as confused and indistinct.” The essential problem for metaphysics is that “philosophers are not agreed about the number of these simple concepts in our knowledge.” One consequence of this is that adepts of this discipline end up “squabbling over words” instead of establishing “settled truths.” Thus, Tetens dismisses metaphysical books as nothing more than “rational novels.”

Finally, I will mention his 1765 essays On the Principles and Benefit of Etymology. In the previous essay he highlighted the importance of words; here he makes the case that studying the origin of words “is not becanizing.” This word was coined by Tetens to denote etymological quackery. As we learn in a footnote, it derives from the name of a 16th century Dutch humanist scholar, Johannes Becanus, whose ridiculous pronouncements on word origin were notorious. Habent sua fata verba, words have their destiny, as Proust’s Professor Brichot might have said.

Tetens uses a nautical analogy when he writes “languages are subject to just as many changes as are peoples. The current of time washes away syllables, letters, connections, words, meanings, while also washing up new ones.” He further deploys heraldic and numismatic analogies to describe the altered meaning of words. “In many words, the root letters or tones betray themselves as soon as one compares it with others bearing the very same root. They are like weapons in heraldry…If this main tone has been lost, then the word is to be regarded as a recast coin, one on which no trace of its first minting has remained.” This leads him to a very important precept.. “One has to consult all the reports in the history of a word’s fortunes; but one must invent none to the very end.”

Tetens yearns for a “critical philosophical lexicon,” of the German language, calling it a “treasure.” This will allow one to “define things as they are – just as the astronomers do with solar eclipses – and not as they are mistakenly represented.” Centuries later, we are no closer to such a lexicon, which is not surprising considering the vast change and expansion of the German language since then. There is thus a touch of irony in the fact the book includes an 18-page German-English glossary, which certainly helps to understand the 18th-century meaning of roughly 200 words.

There is one typo in the book. On pg. 119: “since the those” should read “since those.”

The editors typically allot just a couple of pages to the analysis of the texts; I would like to have seen a more extensive study of each, but the footnotes do provide all the necessary background to people and books Tetens mentions. The translation is a tremendous scholarly effort, one that will bring Tetens back into the mainstream of English-based analysis of 18th century philosophy. It seems remarkable that some 250 years have elapsed during which these important reflections by Tetens have been largely locked away from all but those expert in German.

Editors of the Tetens book: Courtney Fugate (Assoc. Prof. at the American Univ. of Beirut); Curtis Sommerlatte (Postdoctoral scholar at Florida State Univ.); Scott Stapleford (Prof of Philosophy at St. Thomas Univ. in Canada)

Tetens’s Writings on Method, Language, and Anthropology is published by Bloomsbury. It lists for $157.50.